Although the Vienna Gate area is one of the most ancient areas of the capital, it gained its present appearance to a significant extent at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. Inside the castle walls, the Lutheran church (1895) was built first, then the National Archives (1923), and several residential buildings beyond the gate. In 1863, Emil Liedemann, head of the Hungarian Royal National Architectural Directorate, planned a larger residential building at the beginning of today's Ostrom Street.

The Vienna Gate at the end of the 19th century (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The famous engineer died in 1870, but the house went to another star professional, Henrik Wohlfarth, who later became the head of the technical department of the Budapest Public Works Council. He could enjoy the comfort of the house standing in the prestigious neighbourhood for a bit longer, but he also died in 1903. The property remained in his family's possession for nearly a decade and a half and was only sold in 1916 to Jenő Lukács, who also worked in the technical field. He did not design, but only manufactured and traded electrical components: doorbells, transformers, generators. However, he acquired a large fortune from this, which he wanted to express with a representative construction, which is why he bought the plot of land next to the Vienna Gate, on which the house was still standing at the time.

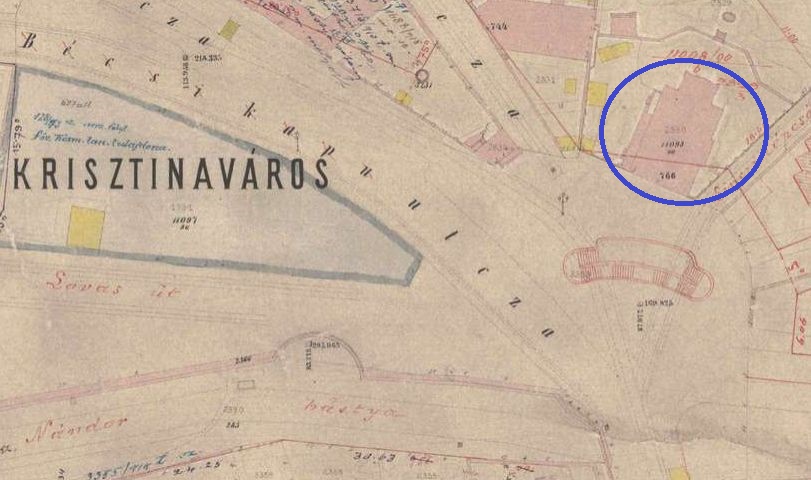

The vicinity of the Vienna Gate on a map from 1874, with the Liedemann-Wohlfarth Villa circled (Source: hungaricana.hu)

Lukács wanted to demolish the building, which was already half a century old, but it still housed several families, typically manual labourers and low-income officials. The owner wanted to evict them, but for years he did not get permission to do so. Instead, the authorities asked him to renovate the house, because its condition had already started to become critical. Lukács did not comply with this, and even deliberately accelerated the depreciation of the building: when it started to leak, he demolished the entire roof instead of repairing it.

Basement floor plan of the new villa (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

In the meantime, World War I ended, and chaotic conditions full of revolutions and terror fell upon the country. The situation was particularly dire in Budapest because soldiers sent back from the front arrived here for the first time, as well as those fleeing from the occupied territories ended up here. Housing poverty was almost unfathomable, and amid the difficult conditions, anti-Semitism also appeared. The case of Jenő Lukács, who was of Jewish origin, caught the attention of some politicians, who even spoke in the Parliament to prevent the factory owner from evicting his tenants. However, by 1922, the house had become life-threatening, so it had to be almost completely demolished.

Jenő Lechner's plan for the main facade of the villa (Source: Kiscelli Museum of Budapest History Museum)

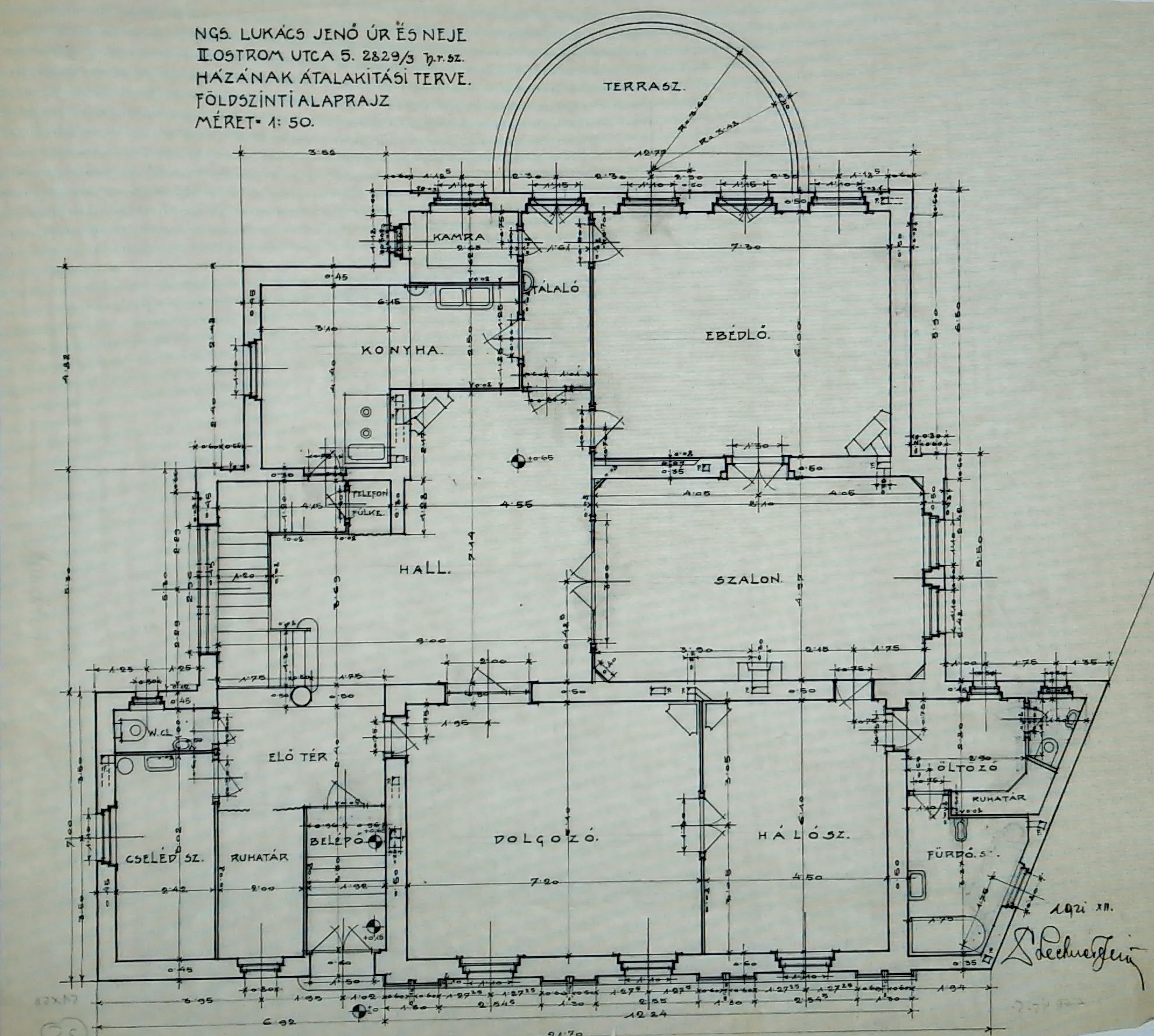

Lukács commissioned Jenő Lechner to prepare the plans for the new villa, who also used the remains of the previous house. But he was thinking of a new building, and he also placed the main facade elsewhere: while before it looked towards the Linz Stairs, the new one is already looking south, towards the Vienna Gate. Despite the fact that he did not have to build the house from scratch, Lechner did not have an easy job, and the terrain conditions presented him with a particularly difficult task.

The plot slopes strongly to the north, but the villa was skilfully adapted to this with a staggered layout. On the one hand, its ground plan is stepped: its southern tract is twice as wide as the northern end overlooking the courtyard, where a semicircular veranda is attached to the building. Its mass system also follows the gradual narrowing: the street front section is three-storey with a basement, while the courtyard no longer has a basement, only the ground-floor veranda, although a terrace was also created on top of it.

Plan of the side facade of the villa (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

The villa is closed by a very flat tent roof, but according to an alternative plan, the architect intended a steeper tent roof for the street tract, which would have increased the difference between the two ends of the building even more. In the end, this was not realised, which was probably due to adaptation to the built environment. There was a towered building on one side (Gulden-Enyedi Villa, designed by Kristóf Schubert, 1884) and the other was still empty, so the Lukács Villa with its flat roof formed a lucky transition between the two. Thanks to the flat roofs, the large terraces do not stand out from the overall picture of the building, even though, there are three of them. It is no wonder since here people can see a truly unparalleled panorama: almost the whole of Pest and even the Danube Bank of Buda can be seen. The largest terrace opened at the northern end of the villa and stretched across the entire width of the building.

The western terrace seen from Ostrom Street (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Jenő Lechner provided the building with a classicist facade, which perfectly expresses his artistic sensibility. He was among the first architects in the country to feel the classicist wave of the 1920s, which permeated all of Europe. After the upheavals of the World War, people wanted security, so they turned to a style that radiated harmony and used the timeless elements of ancient architecture. The core of Jenő Lukács's villa is also characterised by symmetry, but the plot with a romantic location required some asymmetry, so building parts of different sizes were added to it on two sides.

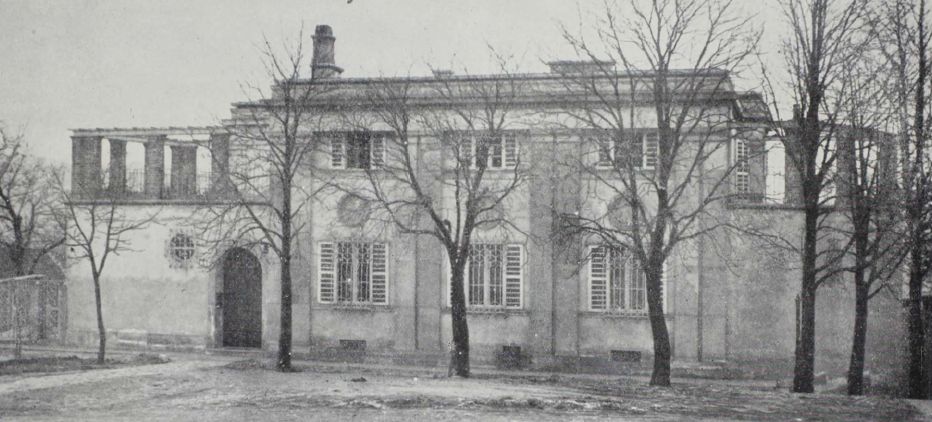

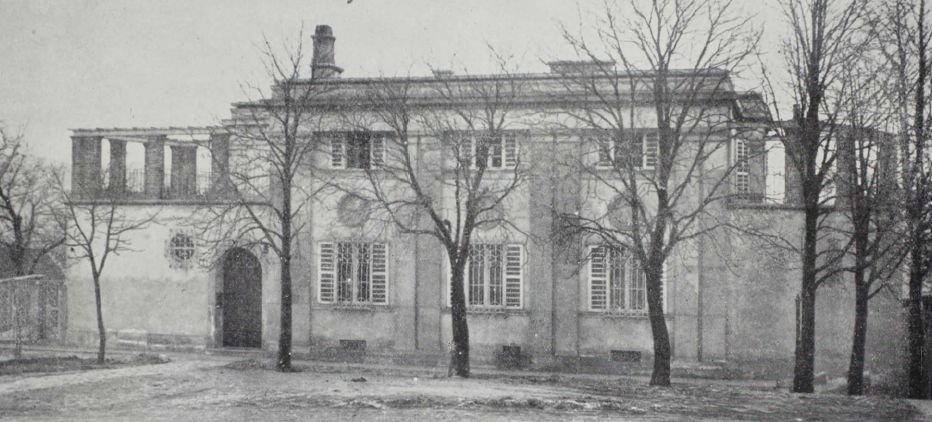

The main facade in the 1920s (Source: Magyar Építőművészet 1924, Issue 1-3)

The white-plastered main facade is divided into three sections by double wall pillars, in which simple, rectangular windows open. The parapets bordering the terraces are also strengthened by pillars, but they are covered with bricks. Pergolas were installed on top of the latter, which could even be covered with plants, thus almost creating the effect of a roof garden. The classicising character of the villa is enhanced by the circular reliefs decorating the main facade, which show allegories of a happy family life and which praise the talent of János Pásztor.

The main facade of the villa is decorated with reliefs by János Pásztor (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Among the additional elements, the parapet railing of the rear terrace is worth mentioning, the grid of which was enlivened by the designer with geometric shapes. The windows on the ground floor of the main facade are also protected by fine-line wrought iron lattices. On the surface of the oak gate at the main entrance, Lechner attached discs, which are probably enlarged wood copies of the rivets fixing the ironwork, thus giving it a very massive appearance reminiscent of castle gates.

Entrance reminiscent of the castle gates (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

For Lukács, representation was important not only in the case of the facade but also in the interior spaces, as he often received illustrious guests. Therefore, he closed the room with a two-story ceiling height in the middle of the villa with a square-mesh plaster ceiling, decorated the plinths of the side walls with dark-stained coffered wainscoting, and above that with floral patterned wallpaper. He also created a fireplace in the corner, which was surrounded by brickwork, and on it, the majolica reliefs of the sculptor Miklós Ligeti raised the solemnity of the room. This central room - which is shown as a hall in the plans - can be called romantic overall, while the adjacent salon, matching the facade, is classicising. The dining room was also located on the ground floor, the main decoration of which was the allegorical mural covering the ceiling, created by Sándor Unghváry. From the hall, an elegant wooden staircase led up to the upper floor, where the bedrooms were located, except for the master of the house. He slept on the ground floor in accordance with the customs of the bourgeoisie of the time.

The ground floor plan of the villa also shows the individual rooms (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

A special staff took care of the residents' comfort: the caretaker's apartment was in the basement, where the laundry room and the central heating boiler were also located. At the end of the basement towards the courtyard, the previously mentioned semi-circular area was opened, which according to its function was a winter garden. From here they could get out into the real garden, where the owner also had a greenhouse built in the mid-1920s.

Lechner's drawings for the interior decoration of the villa (Source: Kiscelli Museum of Budapest History Museum)

The demolition of the previous house and the construction of the villa were carried out by master builder Sándor Havas. He started work as early as 1921, although he only received the permit from the capital in October 1922. Thanks to this, the new villa was inaugurated already that year, on 16 December 1922. If people did not know the story of its origin, they would turn to it with pure admiration. Perhaps the villa is a little ashamed of itself because it has been hiding behind trees for many decades.

Cover photo: The Lukács Villa in 1924 (Source: Magyar Építőművészet, 1924, Issue 1-3)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration