The word Budapest was first used by István Széchenyi in his work Világ [The World] in 1831. He believed that modern Hungary needed a strong capital, which could be created by uniting the historical Buda and the intensively developing Pest. Later, he also wrote a separate book about the twin cities on the Danube, entitled Buda-pesti por és sár [Dust and mud of Buda-Pest], in which he asserted that the two cities - in the absence of higher intervention - would develop on separate paths and would never leave the ranks of provincial settlements. Therefore, he saw artificial intervention as essential, one of whose symbolic and still beautiful tools was the construction of the Chain Bridge.

Count István Széchenyi in a painting by Miklós Barabás (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

His fellow politicians shared his opinion and acted: Bertalan Szemere, as Minister of the Interior, ordered the unification of the cities on 24 June 1849. Buda was considered the capital for historical reasons - as it was the centre of the country for centuries, and Pest according to the laws of April 1848. By this time, however, the Chain Bridge was almost fully completed and was opened to traffic on 20 November 1849. Szemere - who was also the prime minister - justified the unification of the cities as follows:

"...the capital will only be powerful if it has a governing power, it will be prosperous in its life, if it is guided by one soul, one will in its pursuits, it will only be happy if the separate interests melt into a common interest."

With the fall of the War of Independence of 1848-49, the decree lost its validity, but its spirit remained. During the absolutism, they resorted to the tool of centralisation for the sake of easier governance: Óbuda and Buda were merged into a single administrative unit in December 1849, Buda and Pest in November 1850.

Bertalan Szemere in Sándor Kozina's painting (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

The need for a large city was also proven by international examples: in London in 1855, the idea arose to bring the surrounding localities under the administrative authority of the core city, and in Berlin, this was not just planned, but done: after 1861, the city's borders were pushed out in several steps, thus the metropolis of four million was born on the eve of World War I. The processes were similar in the Habsburg Empire: in Vienna, the city wall was demolished between 1861 and 1864, and then the surrounding settlements were also annexed, thus also becoming a metropolis of millions.

The population of Buda and Pest also increased significantly already from the end of the 18th century. From the 1850s, this growth accelerated partly due to natural reproduction, but much more due to the impact of the immigration movement. While 107,000 people lived in the town complex in 1840, in 1880 the population jumped to 356,000. This dynamic development is also explained by the fact that neither Buda nor Pest had developed a suburban system around this time that would have tied the newcomers down.

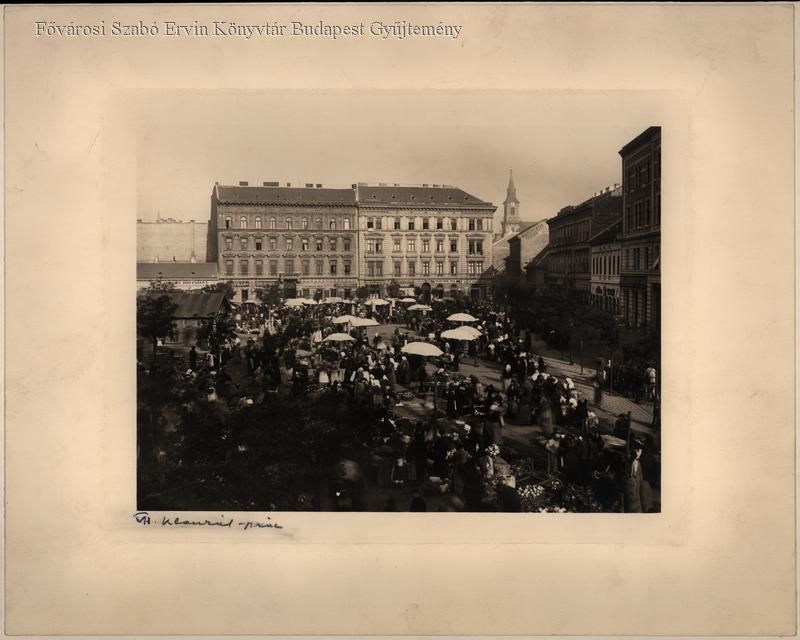

The population of the cities grew dynamically - the picture shows the crowded Klauzál Square market (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 brought about a major turning point in the political field, but the matter of the capital continued straight ahead, albeit only in small steps at first, in various areas of the administration. This was manifested, for example, in education: in 1868, a single joint school board was established over the Pest and Buda school districts. In terms of tax collection, only these two cities were given a special situation: it could be handled by their own tax office, while everywhere else in the country this was the responsibility of the state.

Of course, the increase in population raised many problems, similar to those experienced by the previously mentioned western cities in the middle of the 19th century: London, Paris, Berlin and Vienna also realised that spontaneous urbanisation had to be kept under control by state intervention. In Hungary, this solution was proposed by a well-informed politician on the international scene who, along with István Széchenyi, did the most for the creation of Budapest: Gyula Andrássy. As prime minister, on 23 October 1869, he proposed the establishment of the Budapest Public Works Council, whose task was to integrate the city's infrastructure. The parliament finally established the institution with Act 10 of 1870.

Prime Minister Count Gyula Andrássy (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

In the early 1870s, the two houses of the national assembly worked hard to create the modern organisational order of the independent Hungarian state based on constitutionalism. The autonomy of the county legislative authorities, which generally rejected the Compromise and wanted complete independence, was reduced, while the capital was raised to an even higher level. At the meeting on 19 November 1871, the draft law on the formation and organisation of the Buda-Pest metropolitan legislative authority was discussed for the first time, according to which "Buda and Pest are free royal capitals, as well as Ó-Buda and Margitsziget. These latter being separated from the county of Pest, are united into one legislative authority under the name of the capital city of Buda-Pest." A long debate began, but finally, Act 36 of 1872 stated the city merger. In the justification of the text of the law promulgated on 23 December 1872, the following can be read:

"The Hungarian state needs a centre that is a real gathering place for the interests of the Hungarian state, its main supporter and promoter, that represents the idea of Hungarian statehood in a dignified way and is irresistible to the parts [the parts of the country - ed.] both mentally and financially for the sake of national development exert an attraction.”

Budapest really attracted crowds from both the country and abroad. Many people came from German territories, who, however, assimilated relatively quickly into the Hungarian community. In the middle of the 19th century, assimilation was not yet so intense, around 1850 only 37 per cent of Budapest's population was Hungarian, but by 1880 this proportion had already increased to 55 per cent. Previously, the Germans were in the majority, who gradually developed a Hungarian identity from the end of the 18th century, because they wanted to resemble the Hungarian noble elite. A large number of Slovaks also arrived, who immigrated to the capital due to industrial development. It is interesting that, despite the geographical distance, they came in much larger numbers than, for example, the Hungarian population of the Alföld (Great Plain), who were more connected to the farmland.

The metropolis grew steadily, which the socio-economic crises could not break: in 1872-1873, a cholera epidemic ravaged the country, and in 1873, the collapse of the Vienna Stock Exchange caused the collapse of the Hungarian banking system. The newly established Budapest overcame the obstacles relatively easily: the pathogen was contained by disinfection and quarantine, and the financial sector was helped by mobilising the wealthy. The capital also became attractive for historical nobles: the Festetics's, the Eszterházys, and the Károlys built palaces in Pest after their country estates, setting an example for other families. The construction of the Avenue, a large-scale investment managed by the Budapest Public Works Council, but halted in the financial crisis, was largely taken over and completed by wealthy nobles.

The Avenue looking towards the City Park (Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.107)

The representative Avenue – known today as Andrássy Avenue – was actually part of a comprehensive urban developing plan. This was obtained through a tender, which was announced in 1870 and resulted in the victory of Lajos Lechner. He envisioned the capital as a boulevard-avenue network based on Viennese and Parisian models, and he was able to actively participate in its implementation: in addition to the Avenue, he also managed the construction of the Outer Ring Road and the Danube Banks. Lechner also won the international tender for the canalisation of the capital in 1873, so the drainage network was also designed according to his plans.

The Old Town Hall had a distinctive tower (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.081)

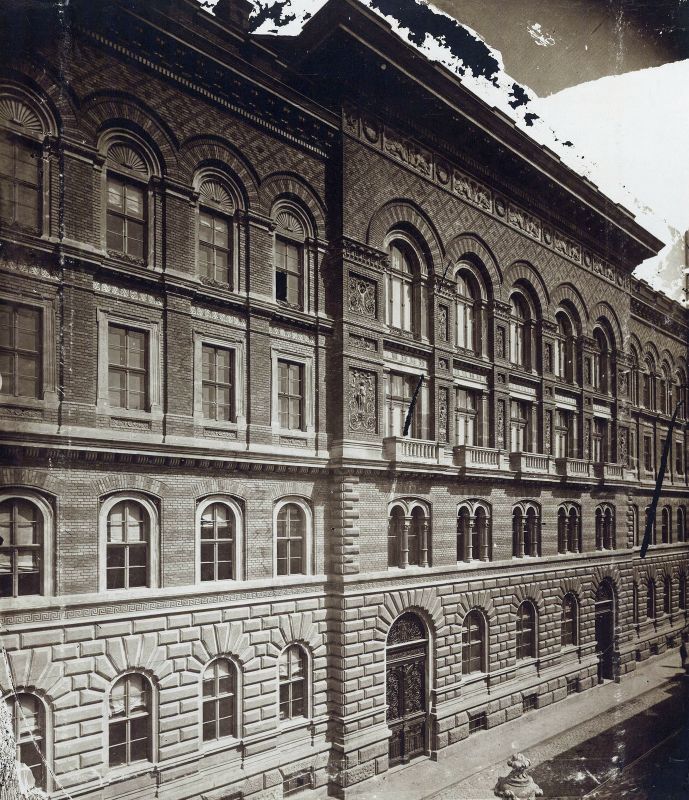

The growth of the population, followed by the merger of the city, also brought with it a rapid increase in the administration, which also required a suitable town hall. The old town hall of Pest was expanded in 1863 according to the plans of József Hild - it was then also given its characteristic tower - but this did not prove to be a lasting solution. As early as 1869, a tender was issued for a new town hall, which was won by Imre Steindl, and according to his plans, the Neo-Renaissance building with a brick facade was completed by the summer of 1873. In that year, the city magistrate moved out of the Baroque walls of the old Buda town hall, since Pest became the headquarters of the united capital.

The Neo-Renaissance building of the New Town Hall (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.037)

The city representatives were also elected in 1873, and with their participation, the first general assembly of the united capital was held on 17 November. However, this did not take place at the New Town Hall, because its ceremonial hall only became usable in 1875. Nevertheless, this small beauty flaw does not detract from the fantastic result that city leaders, businessmen, engineers, and architects created in the following decades. The unification fully fulfilled the hopes attached to it, and a beautiful world city was born in the charming part of the two banks of the Danube.

Cover photo: The Chain Bridge around 1890 (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.08.044)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration