After the expulsion of the Turks, mainly Slovak settlers came to the Rákos Stream area, bringing their evangelical faith with them. This version of Protestantism conquered not only Upper Hungary, but also Transylvania, especially among the Saxon population. Since they lived on the southern borders and were more exposed to enemy incursions over the centuries, they surrounded not only their cities but even their churches with walls. The Saxon fortified churches are now world heritage treasures and breathtaking architectural wonders.

The Lutheran Church in Szászkézd, Romania (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

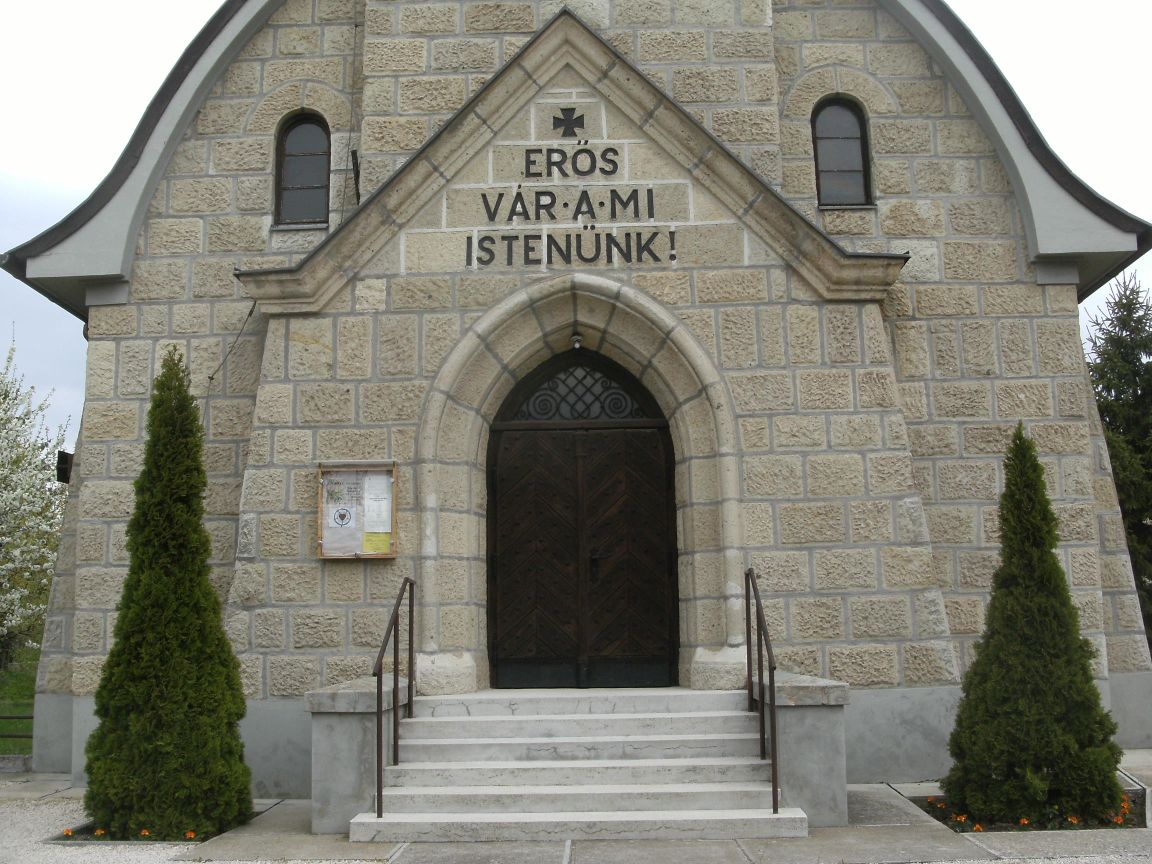

An interesting parallel is that Evangelicals in general had to endure a lot of persecution, not only in our country but throughout Europe. For this reason, they also saw their church community as a fortress, and their form of greeting became "A mighty fortress is our God". This inscription is also used above the gates of their churches. Among the Slovaks who settled in Rákosmente, there was also the need to build a shelter for God, but the opportunity to do so only opened up in the period between the two world wars - previously services were usually held in the school.

'Erős vár a mi Istenünk' [Mighty fortress is our God] - reads above the gate of the Rákosliget church (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

After the Treaty of Trianon, the strengthening of people's faith became more important than anything else, since it was the only way to survive the extremely difficult circumstances. At that time, the country's leadership also became Protestant: the governor and most of the prime ministers were also Reformed, who naturally supported the church-building initiatives. Regardless, the churches had to provide the financial background, which was not an easy task. Fortunately, at least they did not have to worry about getting the plans: Gyula Sándy, one of the star architects of the era, undertook to prepare them for free.

Gyula Sándy in the early 1920s (Source: Private property)

Naturally, Sándy himself was an Evangelical, and he not only practised his faith but also played an important role in the church. He became the clerk of the Buda Evangelical Church District as early as 1891 when he was only twenty-three years old, but he also moved up the ranks: in 1906 he was elected caretaker, and in 1924 he was elected supervisor in the same place. He was also a member of the presbytery, auditor's office and the universal assembly of the Budapest Diocese and the Bánya Church District. Since he graduated as an architect from the Royal Joseph University of Technology, he also put his expertise at the service of the church: he also worked as the chief architect of the University of Hungarian Evangelical Church.

Flensburg's city gate, the Nordertor, is also closed by a stepped gable (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

However, he was not only so active in the church: he taught - first at the Upper Builder Industrial School, then from 1914 at the Technical University - and also designed a lot. Evangelicalism also left its mark on the style of its buildings: it considered the Brick Gothic typical of the North German areas as a model. As a result, he preferred to use unplastered, raw brick facades, as well as the stepped gables so typical of Baltic Sea port cities. Although he borrowed forms and structures from Germany, he was a patriotic Hungarian at heart, and he thought it important that this be reflected in his buildings.

Sándy's early work, the Reformed Church in Hódmezővásárhely-Újváros, 1899 (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

For this reason, from the 1890s onwards, he incorporated the form of Hungarian folk art into his style, the most ancient, intact version of which has survived in Transylvania: beautifully carved wooden eaves, plank frames, and small turrets decorated Sándy's buildings as well. He actually stuck to these until the end of his career. And after Trianon, he gladly turned to the crenellated renaissance, which was the typical style of Upper Hungary in the 16th and 17th centuries. Not surprisingly, he himself came from this area: he was born in Eperjes (Prešov, Slovakia). With the style, he wanted to refer to the unjustly annexed areas, but this was actually also the case with Transylvanian folk art.

The tower of the Lutheran church in Breznóbánya (Brezno, Slovakia) was designed by Sándy and Ernő Foerk in a Crenellated Renaissance style (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

We can see that the appearance of Gyula Sándy's evangelical churches was influenced by impressions coming from different directions, which, however, he mixed in different proportions on the individual buildings, which thus received a more or less individual face. The most unique of them is the one in Rákosliget, which is also the earliest, built in 1931. This is where the fortress-like appearance is most emphatically displayed: the massive stone cladding of its outer walls radiates strength, and it also overlooks the surrounding area from the top of a hill. On its main facade, only narrow windows and porthole-like openings can be seen, and its arched gate is also guarded by a solid wooden door. Its tower is not too tall, but its gable is very characteristic: it closes in steps, which testifies to the knowledge of northern (Baltic Sea) architecture.

The tower of the Lutheran church in Rákosliget (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The Transylvanian motifs are missing from the outside, but there are many inside. The designer covered the peaked vault with planks, which are reinforced with timber, and at the same time create a shape reminiscent of Gothic mesh vaults. The individual fields, on the other hand, are filled with stylised plants that used to decorate the coffered wooden ceilings of Transylvanian churches. The altar at the end of the small church is an even clearer reference to Transylvania, as it follows the structure of the Székely Gates: its beautifully carved and painted pillars support a gabled roof. On the other hand, the altar image itself can be seen in the doorway.

The altar follows the structure of the Székely Gates (Source: Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

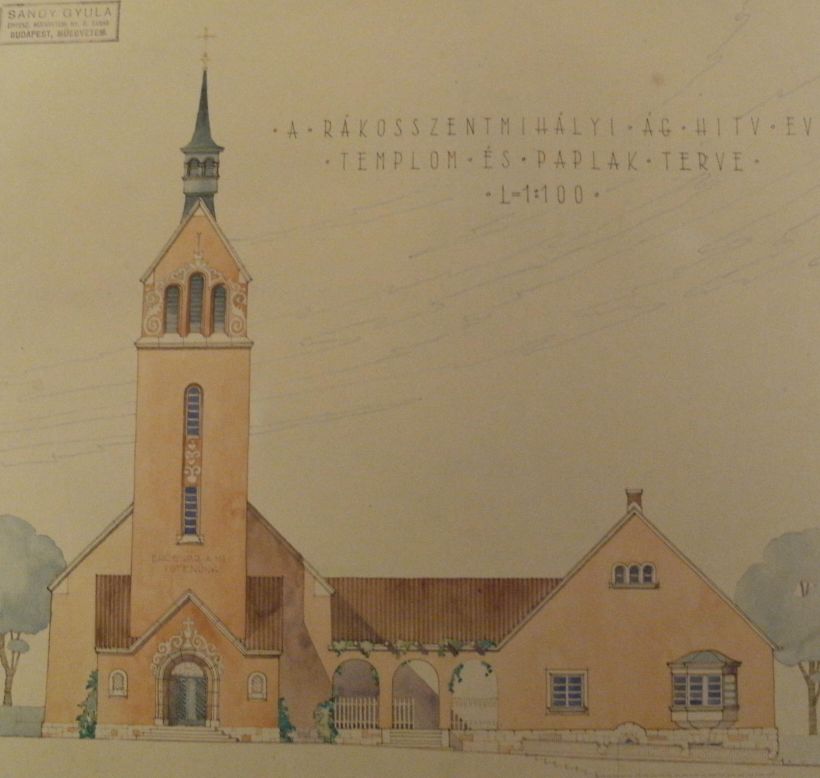

The Lutheran church in Rákosszentmihály is very similar to the one in Rákosliget, but its designer designed a less fortified, more playful exterior. Here too, the tower closes in a stepped gable, but the individual steps are rounded, and the surface was originally covered with plant tendrils and flowers. At the top of the tower, there is currently a cylindrical spire, but the first versions of the plan still featured a pointed turret, typical of Transylvanian churches, whose trunk is pierced by small openings and whose lower edge is scalloped.

The Lutheran church in Rákosszentmihály today (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The Lutheran church in Rákosszentmihály today (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The original plan of the church (Source: Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

In the interior, the shape of the altar structure nicely follows the gable of the tower, it consists of the same rounded steps, but fortunately, the winding flowers made with the intarsia technique have remained on its surface. The pulpit standing next to it also bears witness to the artistic perfection of the wood carving, its parapet is decorated with floral inlays, and the top - the so-called sounding board - is decorated with the dove of the Holy Spirit and a peak decorated with Luther roses.

The altar follows the shape of the gable of the tower (Source: Evangelical National Archives)

The Lutheran church in Rákoshegy, built in 1938-1939, is most reminiscent of Saxon fortified churches, mainly due to the layout of the upper part of the tower: the pointed, pyramid-shaped top is surrounded by four smaller, but similarly shaped spires. The brick facade, on which only relatively narrow windows open, gives it a castle-like appearance. The place of the bells is revealed by Neo-Romanesque twin windows with semi-circular closures, which are separated by stubby columns. The so-called portals, recessed into the wall, also refer to medieval architecture, when the Saxons also built their churches. The gloominess of the walls radiating strength is relieved by only a few small decorations: stylised flowers filling the semicircular field above the entrance - where a Luther rose and the year of construction is also indicated - and a slightly protruding cross on the back wall of the sanctuary.

The fortress-like Lutheran church in Rákoshegy (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The Lutheran church in Rákoscsaba was also built in 1939 and is very close in style to the one in Rákoshegy: its facade is completely covered in brick, and there are smaller spires at the corners of its tower. However, its layout is different, as the tower has been moved to the side. We can also discover a difference in the details: the towers are lower and their tops are flatter, although they are elevated by the star-shaped top ornament typical of Protestant churches. By the way, in the 20th century, evangelicals placed a cross on the top of their churches more often, but as it can be seen here, the star also appeared. However, the spires seen on the last two churches are not only reminiscent of the architecture of the Saxons, but also the Székelys, and in fact, it is even more common in their churches. However, this only makes them even more suitable for reminding us of the lost Transylvania.

The Lutheran church in Rákoscsaba (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The largest Evangelical church in Rákosmente is the one in Rákoskeresztúr, as the congregation is much more populous than the others. Precisely because of this, the need to build a church arose long before, and it was inaugurated in 1800. With the increase in the population, a new church would have been needed already at the end of the 19th century, but it was not until the 1930s that the financial basis was created. Sándy designed a strong fortress here as well: the brickwork, the narrow windows, but especially the staircases on the edges of the main facade, reminiscent of a round bastion, all radiate protection. Above the entrance and at the foot of the spire, there is a crenellation, which, however, with its gently undulating outline, resembles flower petals, as if it were a stylised tulip - this can be interpreted as a reference to folk art.

The tower of the Lutheran church in Rákoskeresztúr (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The Transylvanian folk architecture is more spectacular in the interior, mainly thanks to the many trees: the walls are covered with panelling made of brown-stained boards, on top of which the same tulip pattern that we saw on the exterior runs. The ends of the pews were also carved into a tulip shape by the carpenters, and the roof above the pulpit – the so-called sounding board– is also crowned with crenellations. The rarity of this church is the ceiling, which is covered with planks laid in a herringbone pattern as if it was a parquet. The simple, peasant life is also represented by the charming wall brackets holding the lamps, which are decorated with ears of wheat, grape leaves and bunches of grapes.

The interior of the church in Rákoskeresztúr (Source: Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

Along the Rákos Stream, small villages and small towns have indeed sprung up, with an almost village-like cityscape. However, on 1 January 1950, when Greater Budapest was created, these were annexed to the capital. Although they have been forming the 16th and 17th districts for almost three-quarters of a century, they have largely preserved their rural character, to which these evangelical churches, reminiscent of Transylvanian villages, fit perfectly.

Cover photo: The Rákoshegy Lutheran Church (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration