Ernő Foerk was born on 3 February 1868 in Temesvár (Timișoara, Romania). After graduating from the College of Applied Arts, he continued his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, where the great Friedrich Schmidt was his master. He was also noticed by Imre Steindl, who invited him as a teaching assistant at the University of Technology, as well as to the office that built the Parliament, where he was entrusted with the tasks of designing the furnishing. Even at a young age, he gathered very valuable experience, which he soon had the opportunity to pass on, as he taught at the Felső Építő Ipariskola [Upper Civil Engineering School] from the mid-1890s. Here he formed a good friendship with his colleague Gyula Sándy, with whom they successfully participated in numerous design competitions, and several of their creations were realised.

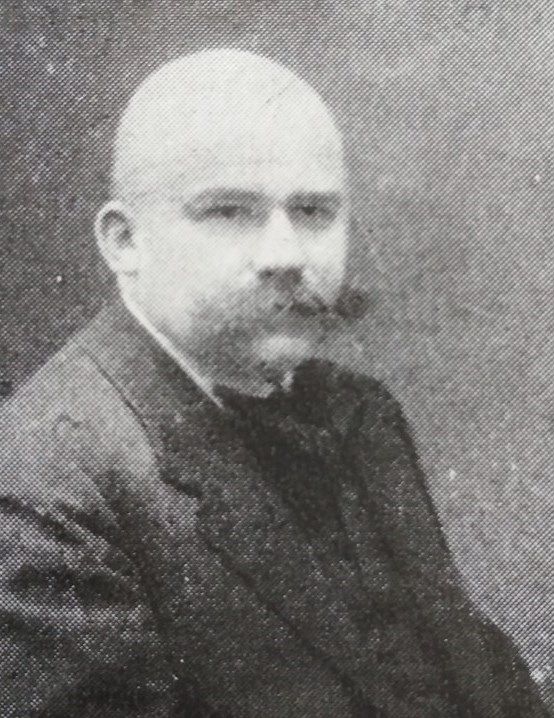

Ernő Foerk in the 1920s (Source: The anniversary album of the 50-year-old Vállalkozók Lapja, 1929)

He mixed the neo-Gothic style he learned from his masters with the Hungarian Art Nouveau style, borrowing mainly the brick strips from the latter. He also preferred to use brick on the facades because he was captivated by the medieval Lombard brick churches during his travels in Italy. Foerk was a real artist, while Sándy was more of an architect with an engineering mentality, so they complemented each other perfectly: the latter designed the floor plans and structures requiring complex calculations, leaving the former more time to draw eye-catching facades.

From the second half of the 1900s, he worked more with Gyula Petrovácz, and their collaboration is especially praised by churches, which were built on the order of the Archbishop of Kalocsa. In addition to the design of several smaller buildings, Foerk also restored the Baroque Kalocsa Cathedral. His real field of expertise, however, was the Middle Ages, and he put this into practice in his monumental work: he travelled to the countryside with his industrial school students in the summer to study a Romanesque or Gothic monument.

Part of the Tripolisz housing estate (Source: Fortepan/No.: 41104)

In the meantime, the capital city continued to expand and at the beginning of the 1910s, the part of Angyalföld north of the Rákos Stream began to be incorporated. In the area between today's Váci Road and Béke Road, a settlement consisting of ground-floor barracks was erected, in which mainly one-room emergency apartments were created. Along with the residents, of course, the pubs also appeared, one of them was called Tripolisz, the good-sounding name then stuck to the entire settlement. By the way, Tripoli is the capital of Libya, for the possession of which Italy launched a campaign against Turkey in 1911, so it was often featured in the columns of the newspapers. Perhaps this also contributed to the naming of the pub and the settlement. Please note that the latter never became an official name - it was called Palotai Street small residential estate - it was only referred to as such in everyday speech.

Tripolisz was almost a slum and thus one of the capital's most dangerous housing estates. Because of this, the residents had an increased need for spiritual care, which was provided by Carmelite fathers from 1917 within the framework of the Hóvirág Chapel Auxiliary Association. Masses were held in the gymnasium of the Tomori Road school, which the Catholic parish founded in 1923 received from the Capital Education Authority. While until then the word chapel was only used in the name of the Association, after that they were able to turn the gymnasium into a truly consecrated mass place, and on 1 December 1923, the Archbishop's High Authority assigned a priest to the parish, Jenő Mester.

The former Tripolisz, now officially St. Michael's Parish Church of Budapest-Angyalföld (Photo: Gyöngyvér Havas/pestbuda.hu)

In the mutilated country between the two world wars, the government paid special attention to religion, as the extremely difficult circumstances could only be overcome with strong faith. They also supported the establishment of churches, which also positively boosted the construction industry, so it was a double benefit. In Budapest, the Council of the Capital financially supported such investments by the parishes, which was also necessary for Tripolisz because the vast majority of the population lived in extreme poverty, and the donations of the faithful could not have covered the costs by themselves.

The Votive Church in Szeged (Photo: Krisztina Bélavári/Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

The fate of the infamous neighbourhood and the architect Ernő Foerk met at this point: in 1929, he was entrusted with the preparation of the plans. At that time, he had been working on the Votive Church in Szeged for more than a decade and a half, so it is no wonder that he could not get rid of its basic ideas: he also designed a church with two towers and a brick facade in Tripolisz. Of course, its size is much smaller, but the floor plan in the form of a Latin cross still covers nine hundred square metres. Its structure is of the so-called basilical system, that is, in the longer leg of the cross, three naves run parallel, of which the middle one is higher and wider than the side ones. The sanctuary formed at the end of the longhouse is closed in a semicircular arch and is bordered by a low corridor.

The side facade of St. Michael's Parish Church in Tripolisz (Photo: Krisztina Bélavári/Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

At first glance, common points also appear on the facade, as light plastered fields blend into the red brick surface on both sides, a large rose window opens in the middle of the main facade, and above it, the pediment closes in a triangular shape. In the details, however, Foerk tried to deviate from the cathedral on the Tisza Bank. While that one is made lively by many more articulate elements (cornices, pillars, arcades, dwarf gallery) and the towers are further apart, the one in Tripolisz is much more compact: the towers are closely connected to the main facade, which is decorated with planar, geometric fields. Foerk already used brick triangles, squares, and rhombuses in his turn-of-the-century buildings, which can be seen here as well. In Szeged, these were probably not given as much space, because there he only reworked Frigyes Schulek's designs made at the beginning of the 20th century.

Works of art were also added to the main facade of the church (Photo: Krisztina Bélavári/Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

A significant difference is that the dome on the Votive Church also emphasises the meeting of the nave and the transept, but in Tripolisz it was no longer possible to do so from the financial framework. Attention was paid to the decoration since according to the decree of the Capital, 2 per cent of the total budget had to be spent on artistic creations. There are fewer of them on the facade and they are concentrated on the main facade: the gilded alpha and omega letters on both sides of the rose window express God's eternity, and the tympanum is decorated with a relief of the Archangel St. Michael, the patron saint of the church.

The ornate interior of the church (Photo: Krisztina Bélavári/Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

Entering the building, a wonderful sight unfolds before the visitors, as the walls are covered with continuous colourful paintings, which also creates the illusion that it is made of marble. The flat ceiling is also enlivened by a coffered arrangement, the compartments of which are filled with gilded ornamentation. The most beautiful part of the interior is the sanctuary, whose quarter-spherical vault is covered with a representation of Heaven. The work of Jenő Dénes depicts the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit between clouds - that is, the Holy Trinity - and a multitude of saints on the edges. The original main altar was decorated with the figure of the Archangel Saint Michael, but it was replaced in 1980 with the fire-enamel work that can still be seen today. Of course, the titular saint also appears here, but on both sides, people can also see the archangels, Gabriel and Raphael.

Ernő Foerk's relief on the Votive Church in Szeged (Photo: Krisztina Bélavári/Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

Ernő Foerk's architectural qualities and brilliant sense of beauty are also evidenced by the Tripolisz church. The fruit of his work was doubly ripe in 1930, as the Tripolisz and Szeged churches were consecrated one month apart: the former on 29 September, the latter on 24 October. However, not even four years passed and death suddenly took him from this world. He was laid to rest in the Votive Church in Szeged, but his memory is also preserved in the capital. Five years ago, on the one-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of his birth, Pestbuda presented his life work in detail, which can be read here in Hungarian.

Cover photo: The St. Michael's Parish Church (Photo: Krisztina Bélavári/Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration