Kálmán Rózsahegyi was born on 6 October 1873 in Endrőd, Békés County. Following the example of his foster father, Ödön Rózsahegyi, he entered the stage career and graduated from the Academy of Drama in 1892. At the beginning, he got the opportunity to introduce himself in the countryside: he played in theatres in Debrecen and then in Cluj-Napoca, and he only came to the capital in 1898: first, he signed a contract with the Hungarian Theatre and then the National Theatre. Together with his wife, Angéla Hevesi, he founded an acting school in 1909, which enjoyed great popularity for decades. He was loyal to the National's company, which elected him one of its permanent members in 1923. Thanks to his talent, he was able to portray a diverse range of characters, but in the 1910s and 1920s, he became really popular with his cabaret roles, which is how he reached the United States of America in 1926.

Kálmán Rózsahegyi (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

His fans built the villa in an up-and-coming part of Buda, in Németvölgy, which was still a sparsely populated area in the 1920s. On the other hand, the capital was counting on the future growth of the population and regulated the area in such a way that as many residential buildings as possible could be built here, so the street had to be built in with closed rows. The reason was clear to everyone at the time, since immediately after the Treaty of Trianon, Budapest was tormented by a truly terrible lack of housing: the masses who had moved in in previous decades were also supplemented by refugees from across the border.

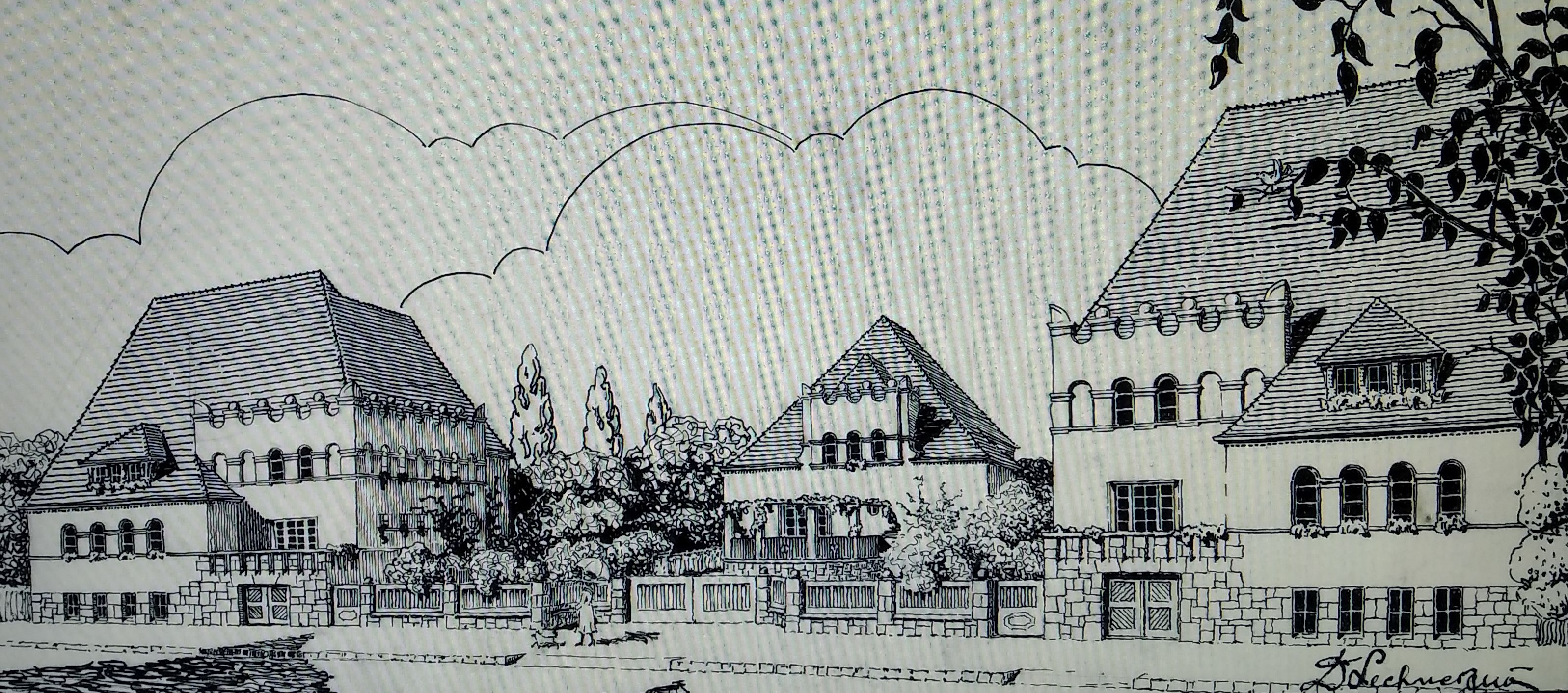

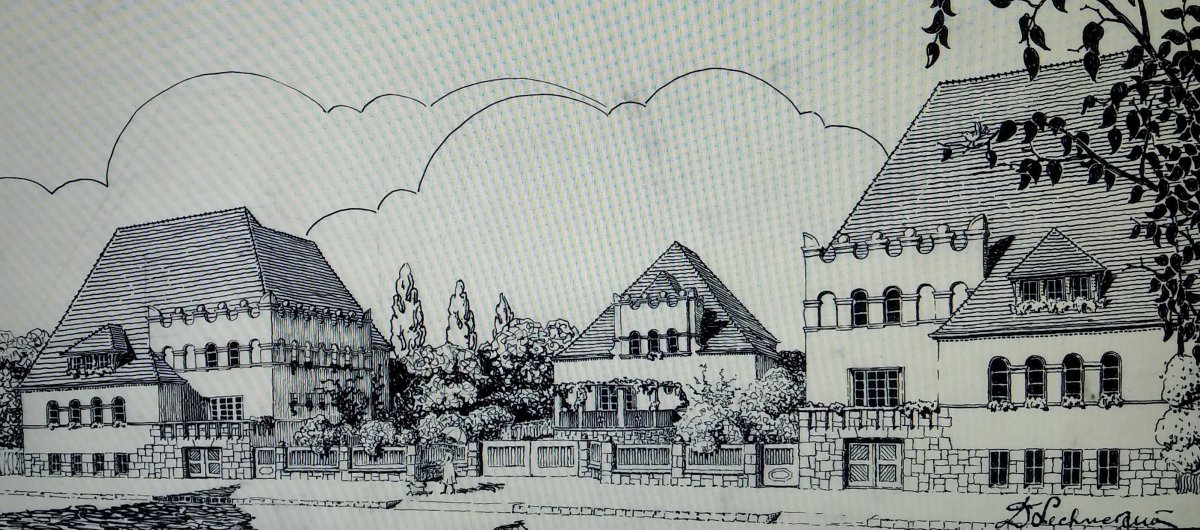

At the same time as the actor's villa, two residential buildings had to be built on the Hantos (today's Tartsay Vilmos) Street lot, which would have surrounded Rózsahegyi's house according to the building ordinance. Of course, this would have greatly reduced its value, making a truly picturesque appearance impossible. Jenő Lechner outwitted the building regulations by planning a spacious front garden in front of the actor's house while placing the two residential buildings completely on the street front. In this way, a free-standing villa was created, the rural atmosphere of which was enhanced by the wonderful view of Svábhegy. Their current address is 11–13–15 Tartsay Vilmos Street, 12th District.

Perspective plan of the three villas (Source: Kiscelli Museum of Budapest History Museum)

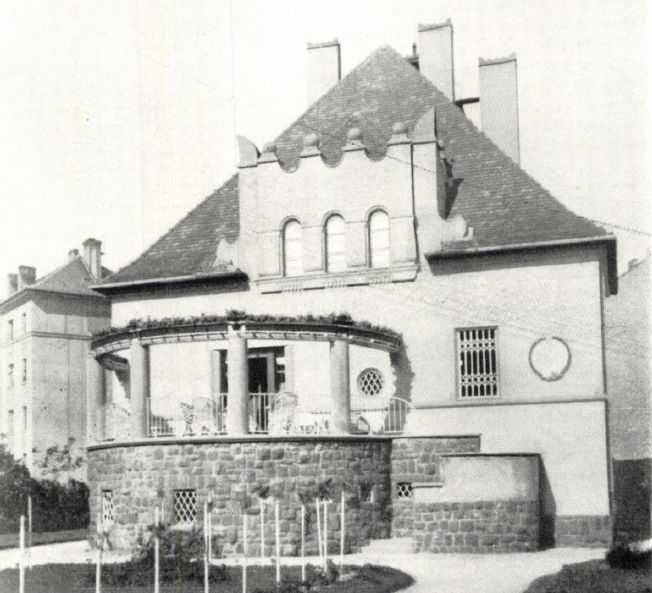

Lechner also emphasised its uniqueness with the building's style: he mostly used elements of the crenellated renaissance, which dates back to the 16-17th centuries and was fashionable in the Highlands, however, he did not really revive the historicism of the 19th century. The sight of the crenellations was therefore unusual on the streets of Budapest and captured attention. At the same time, due to the associations linked to castle architecture, it gave the villa a noble sense of privacy and inaccessibility, thus giving it prestige. The rustic stone covering of the plinth of the building was also in line with this.

The villa of Kálmán Rózsahegyi in the 1920s (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 5, 1928)

Jenő Lechner started using this rare style at the very beginning of the 20th century because he saw the possibility of creating a national architectural style in it. His uncle, Ödön Lechner, also dedicated his life to this, and at the turn of the century he created a new style, which can be admired today, but in his time it was rejected by the majority of society. Jenő believed that greater success could be achieved by transforming an already existing style. He chose the crenellated renaissance because it was actually a Hungarian style, although, in addition to the Highlands, its memories also arose in the southern part of Poland. After the Treaty of Trianon, the use of this style could also refer to the lost northern part of the country, so according to Jenő Lechner, it was a lucky choice from several points of view.

However, behind the castle-like exterior, a modern interior equipped with all the luxury was hidden. This was hinted at by the semicircular terrace extending forward from the main facade, on which a pergola covered with plants ran along. This light, beautiful solution was meant to offset the excessive gloom resulting from the castle-like appearance. Unfortunately, it is no longer visible, but the terrace's low fence remains, which the designer tried to make Hungarian with so-called Hungarian knots [vitézkötés] - the motif comes from the clothing of the hussars.

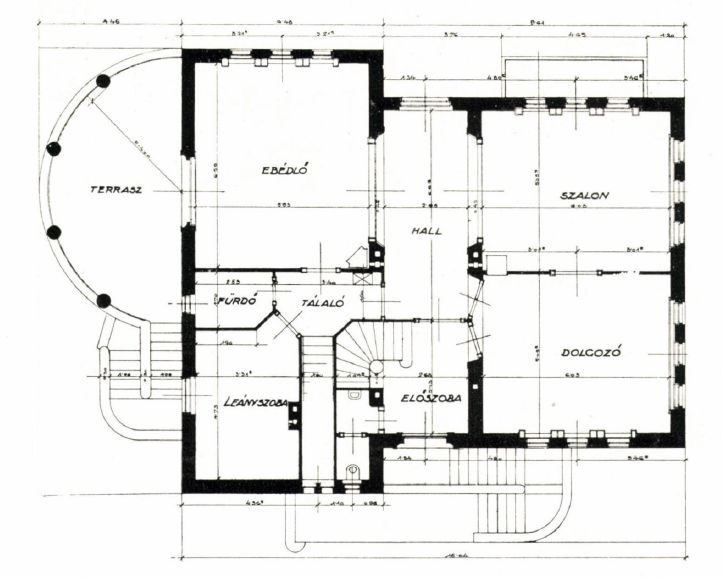

Ground floor plan of the villa (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 5, 1928)

The terrace expanded the space of a spacious dining room, which filled most of the southern half of the villa. People could enter the building here as well because a staircase led up to the terrace. However, the main entrance - which also opened on the mezzanine level - was located in the middle of the eastern side. Upon entering this, a small vestibule and a long hall were revealed. The latter functioned as a "distribution" room: turning left from here, the path led to the dining room, which also included a separate serving room and a servant's room. Even the maid was provided with good conditions here, as she had her own bath. To the right of the hall was another social room, the salon, from which they could go out onto a wide balcony.

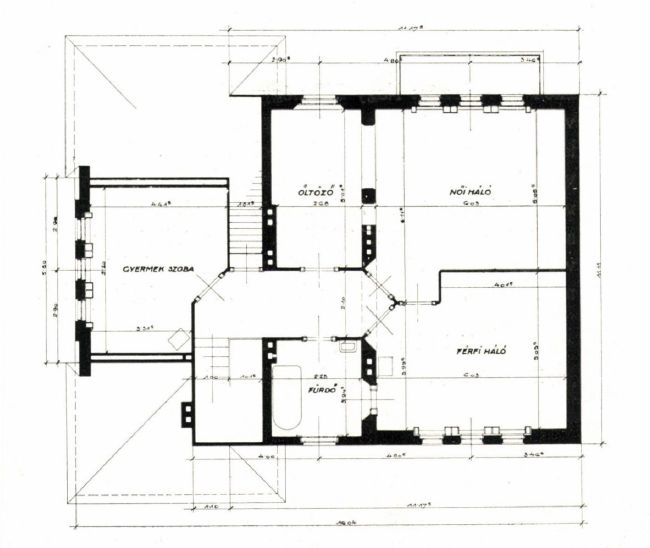

Floor plan of the villa (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 5, 1928)

Rózsahegyi's study was also arranged on the mezzanine floor, where the fans collected many memorabilia for him from the main stages of his career: photographs, wreaths and even a statue. The first floor was occupied only by private spaces, the bedrooms. As was customary at the time, the husband and wife had separate rooms, but they were placed next to each other at the northern end of the building. A dressing room was also opened from the women's bedroom, and the bathroom was created next to Rózsahegyi's room. At the far, narrower end of the floor was the children's room, where the parents pleased them with the most beautiful view from their window: they could enjoy the front garden.

In the basement under the building, a laundry room and a garage were built, and the boiler for the central heating was also located there. The villa not only met the comfort requirements, but its interior design was also aesthetic, for example, its floor was covered with marble mosaic tiles and beautifully laid wooden parquet. According to the plans, the designer envisioned the front garden as a geometrically structured, so-called French garden, in which rows of trees separated it from the courtyards of the two neighbouring residential buildings.

The main facade of the villa at 13 Tartsay Vilmos Street nowadays (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

These two residential houses were designed by Lechner in the same style, and they were similar in size to the middle one, so perhaps it is more correct to call them residential villas. These also included an identical semi-circular terrace, under which it was also possible to create a conservatory. The only significant difference was in their street facades, because the designer formed their corners as a bastion-like mass, on top of which a crenellation line ending in a sphere marched along. These spherical ornaments were also repeated on the top of the stone fence in front of the villas.

Building at 11 Tartsay Vilmos Street (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

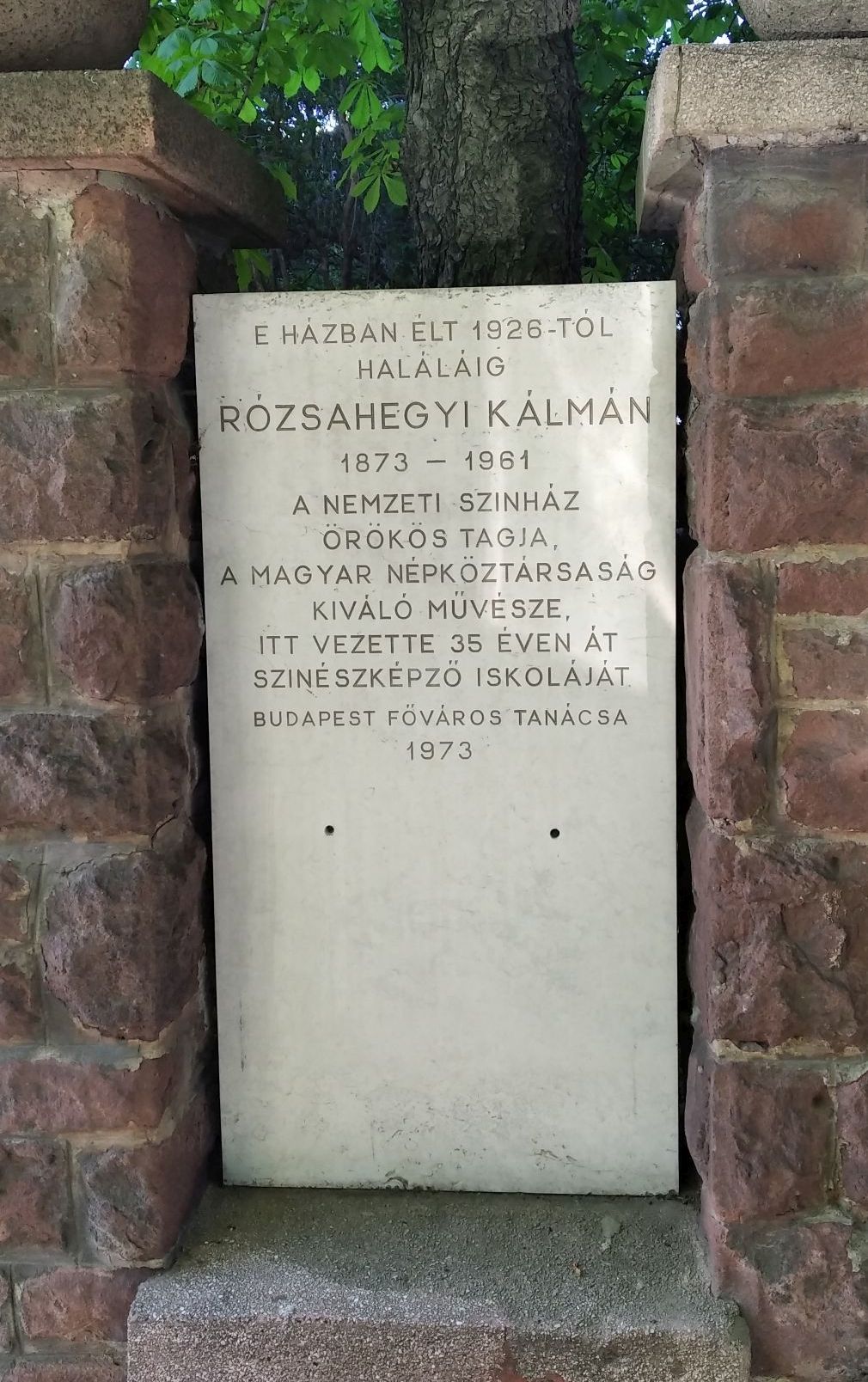

Jenő Lechner drew up the plans for the villas during 1923-1924, their construction soon began and was completed by 1925. Kálmán Rózsahegyi and his family moved into their new home in 1926 and lived here until the end of his life. They also received their students from their acting school here, who could usually present their exam performance on the stage of the nearby MOM Cultural Centre.

Plaque commemorating Kálmán Rózsahegyi on the fence (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

His film career began in the 1930s: he showed his talent in works that are still popular to this day such as My Daughter is Not Like That [Az én lányom nem olyan] (1937, directed by László Vajda) or Wild Rose [Vadrózsa] (1939, directed by Béla Balogh). Due to his origins, he was not allowed to perform in the first half of the 1940s, but he was not accepted back into the National Theatre after the war either. He did not remain without work, he played in the Comedy Theatre of Budapest, Hungarian Theatre and Madách Theatre, among others, as well as in movies (The State Department Store - Állami áruház, 1952, directed by Viktor Gertler; Liliomfi, 1954, directed by Károly Makk). His work was recognised with the Outstanding Artist award in 1960. He died on 27 August 1961.

Cover photo: Perspective plan of the three villas (Source: Kiscelli Museum of Budapest History Museum)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration