In Budapest, the construction of multi-storey residential houses peaked in the years immediately preceding World War I - at that time, almost unlimited loans were available to construction companies, which ceased after the war. Therefore, in the period between the two world wars, smaller buildings came into vogue, which, however, also accommodated more spacious - two- and three-room - flats.

People wanted not only bigger flats but also a healthier living environment, so migration started from the crowded Pest to the green areas of Buda. The increase in demand drove up the land prices here, which was countered by the construction of multi-flat houses. According to the regulations, free-standing, villa-like buildings had to be built in the beautiful landscape environment, so they were called condominiums or, if they were built specifically for investment purposes, rental villas.

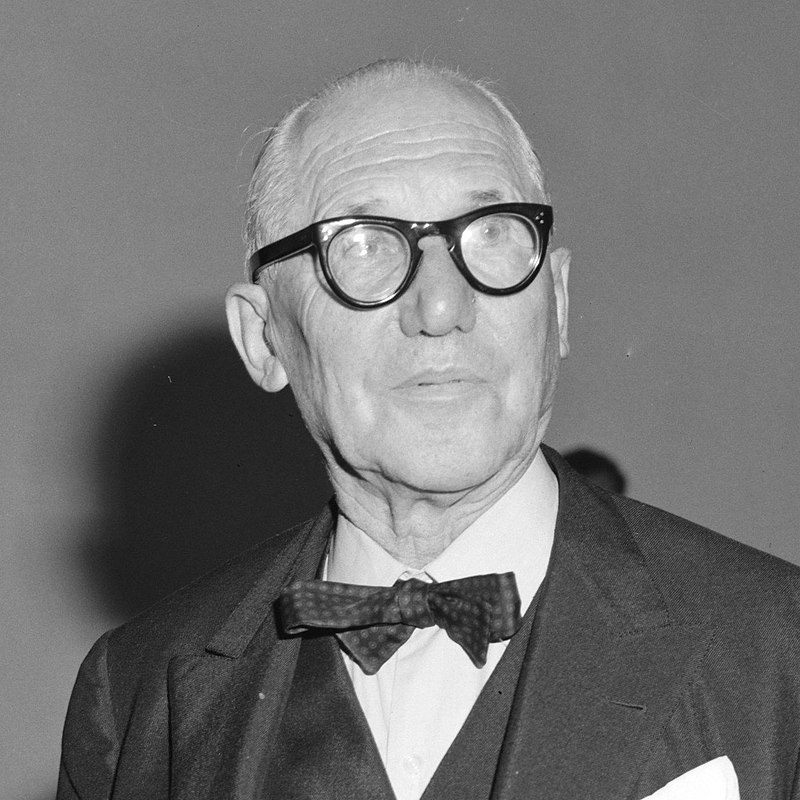

Le Corbusier - originally named Charles-Edouard Jeanneret - was the main theorist of modern architecture (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

Not only was the concept new, but from the beginning of the thirties the style of more and more villas followed a new trend, modernism. Its roots go back to the beginning of the 1910s, but it spread after World War I, during the period of the rampant housing shortage. Its essence is simplicity and good usability: while previously the main role was played by the facades, here, it is the reasonably distributed floor plan.

One of the main advocates of the style was Le Corbusier, who in 1926 defined the five characteristics of modern architecture as follows:

1. Setting the building on pilotis so that it does not take away land from nature

2. With the pillar frame, free floor plan design unrestrained from the supporting structure can be ensured

3. Free design of the no longer load-bearing facade

4. Ribboned windows, which increase the level of lighting and provide a better view of the outside space

5. A flat roof that allows for the creation of a roof garden

In Hungary, the conquest of modern architecture only started at the end of the 1920s, as the conservative public mood after the Treaty of Trianon was not favourable to it. Even then, it did not become dominant, but was accepted and used by more and more architects, and sometimes even great changes took place. For example, Lajos Kozma designed Neo-Baroque buildings and works of applied art during most of the 1920s, but in the following decade, he became an enthusiastic supporter of modernism. At the beginning of the 20th century, Jenő Lechner was still attracted by Art Nouveau and the crenellated renaissance, which was replaced by classicism in the twenties, from where he switched to the modern style at the very beginning of the 1930s.

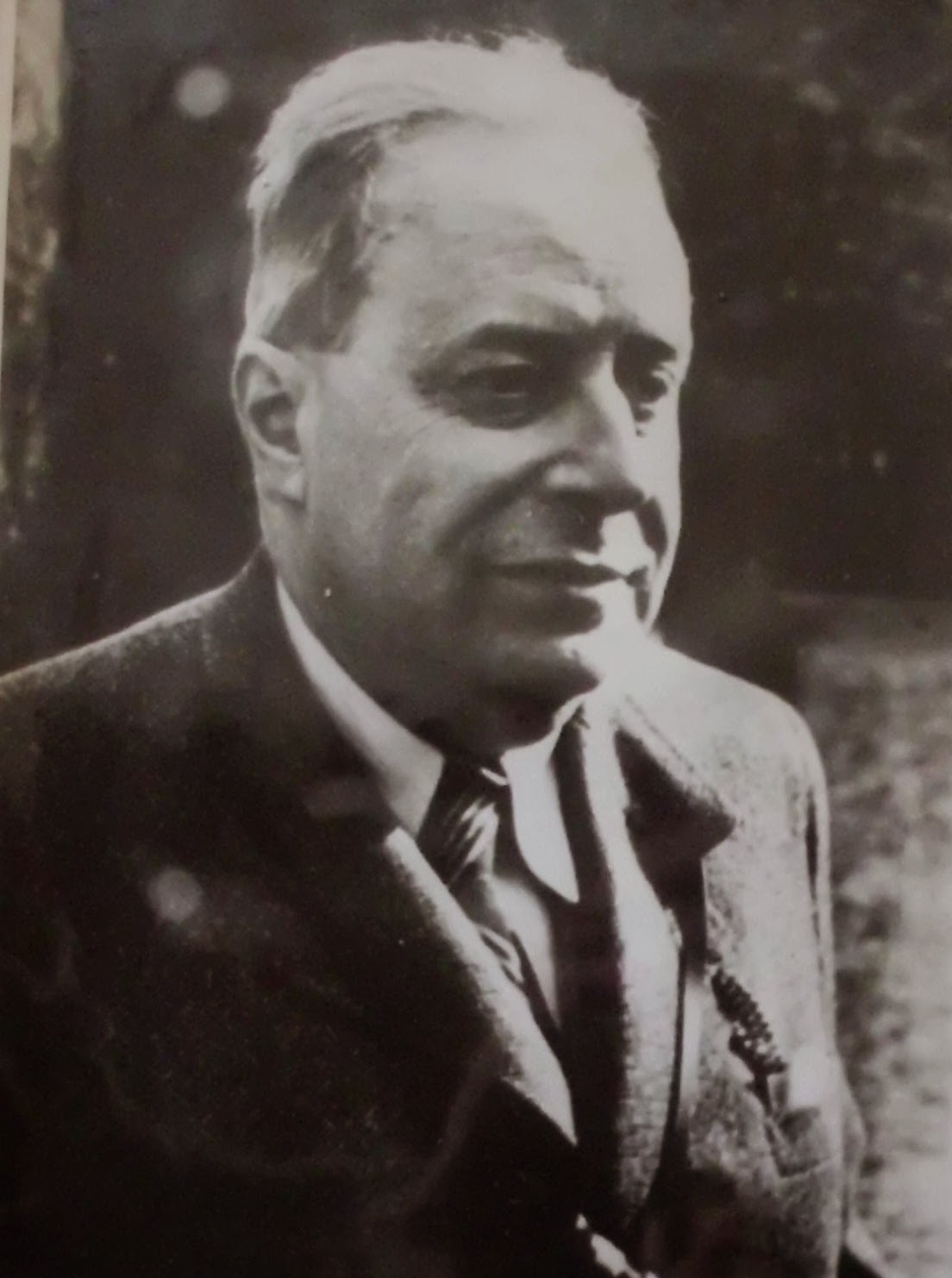

Jenő Lechner designed in the modern style from the early 1930s (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

Lechner came from a famous family of architects, his uncle named Ödön was the most outstanding figure of the Hungarian Art Nouveau. Jenő Lechner owes not only his name but also his brilliant talent to the fact that he was commissioned to design many residential buildings and villas from a young age. From these, he also acquired a considerable fortune, which he wisely invested in real estate: he built a rental villa on Gellért Hill, which was becoming popular. The building on the corner of Nagyboldogasszony (today Ménesi) Road and Alsóhegy Street (87 Ménesi Road) was built in 1931-1932 according to the principles of modern architecture.

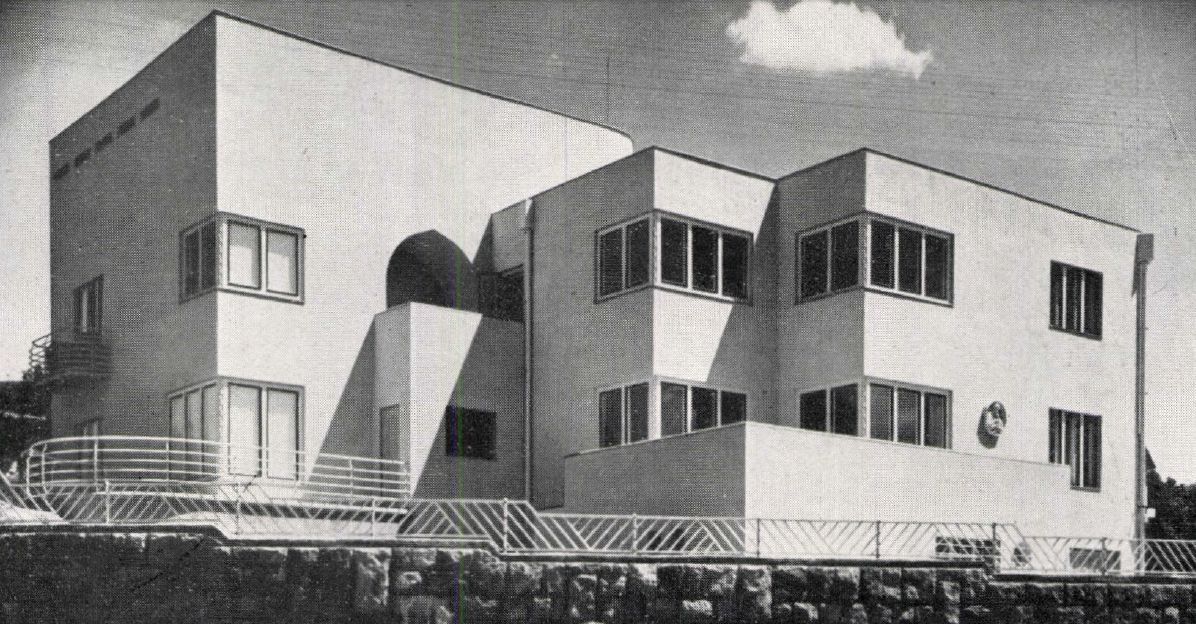

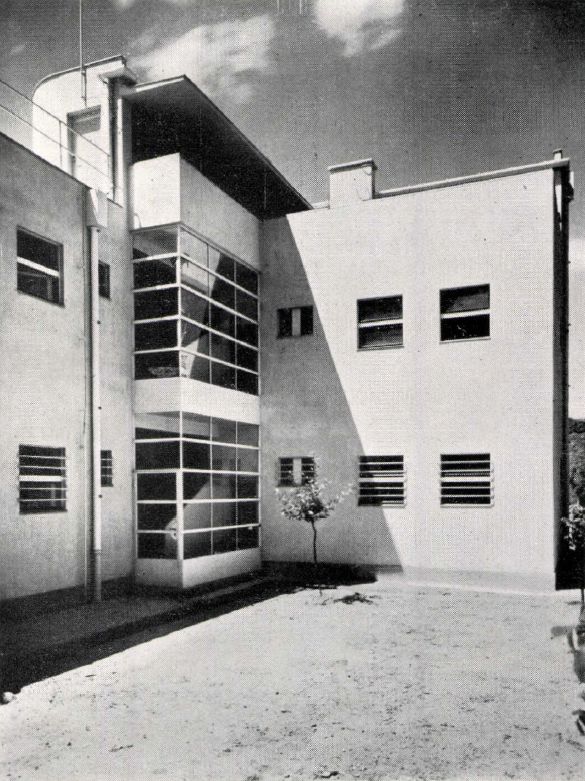

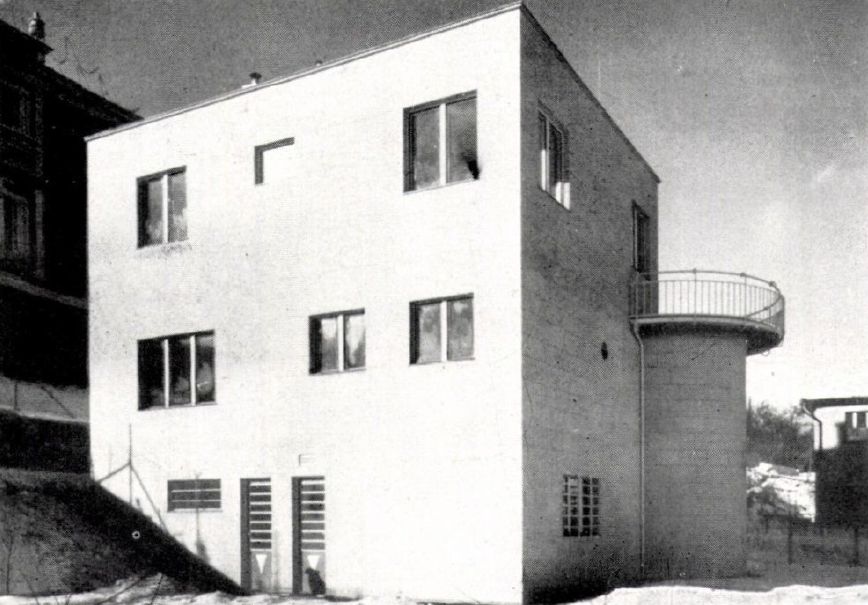

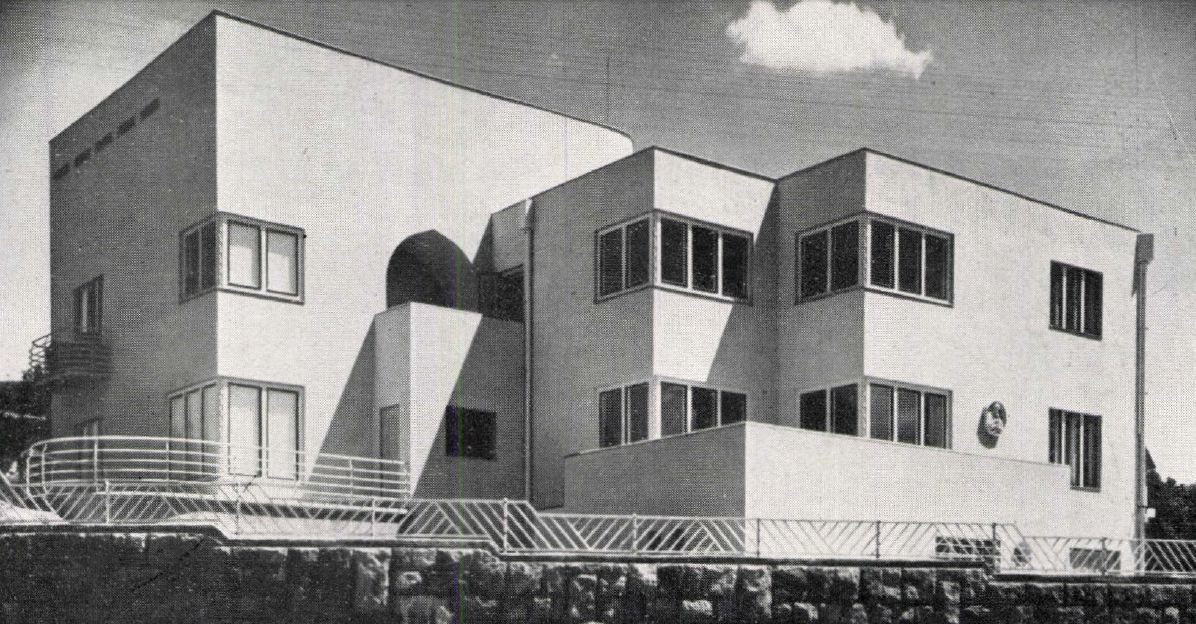

The rental villa at 87 Ménesi Road between the two world wars (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 8, 1932)

Above all, Lechner ensured good usability by placing the individual flats as far apart as possible, so that the residents did not disturb each other. He achieved this by dividing the building into two tracts, which were in contact with each other only on a small section, the shared staircase. Due to terrain conditions, the two blocks also slide next to each other in space: the northern one rises one level higher. The designer also enhanced his stepped mass system by cutting out the corner of the southern block in order to place a corner terrace there. From the northern tract, a semicircular terrace stepped in front of the plane of the facade.

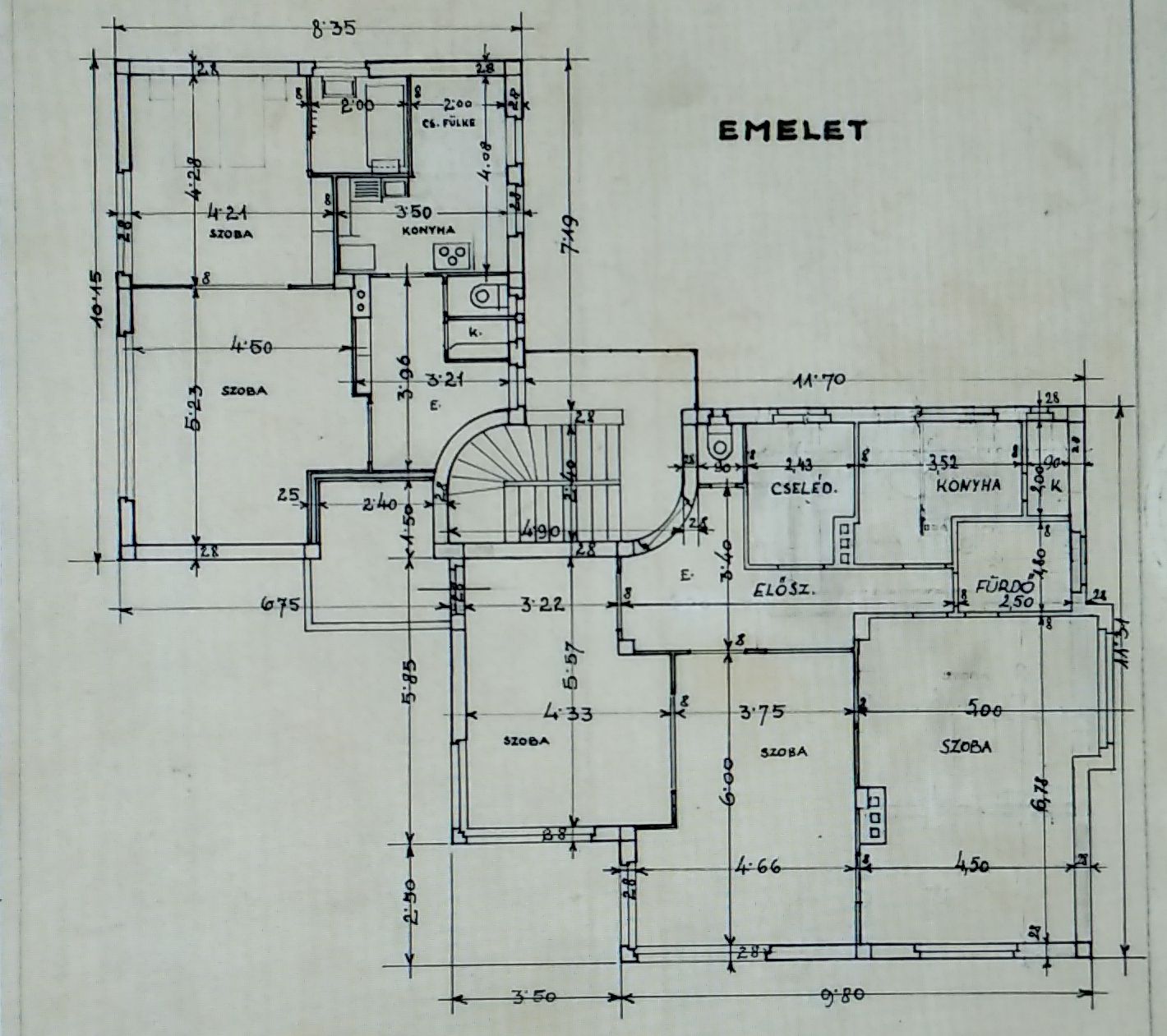

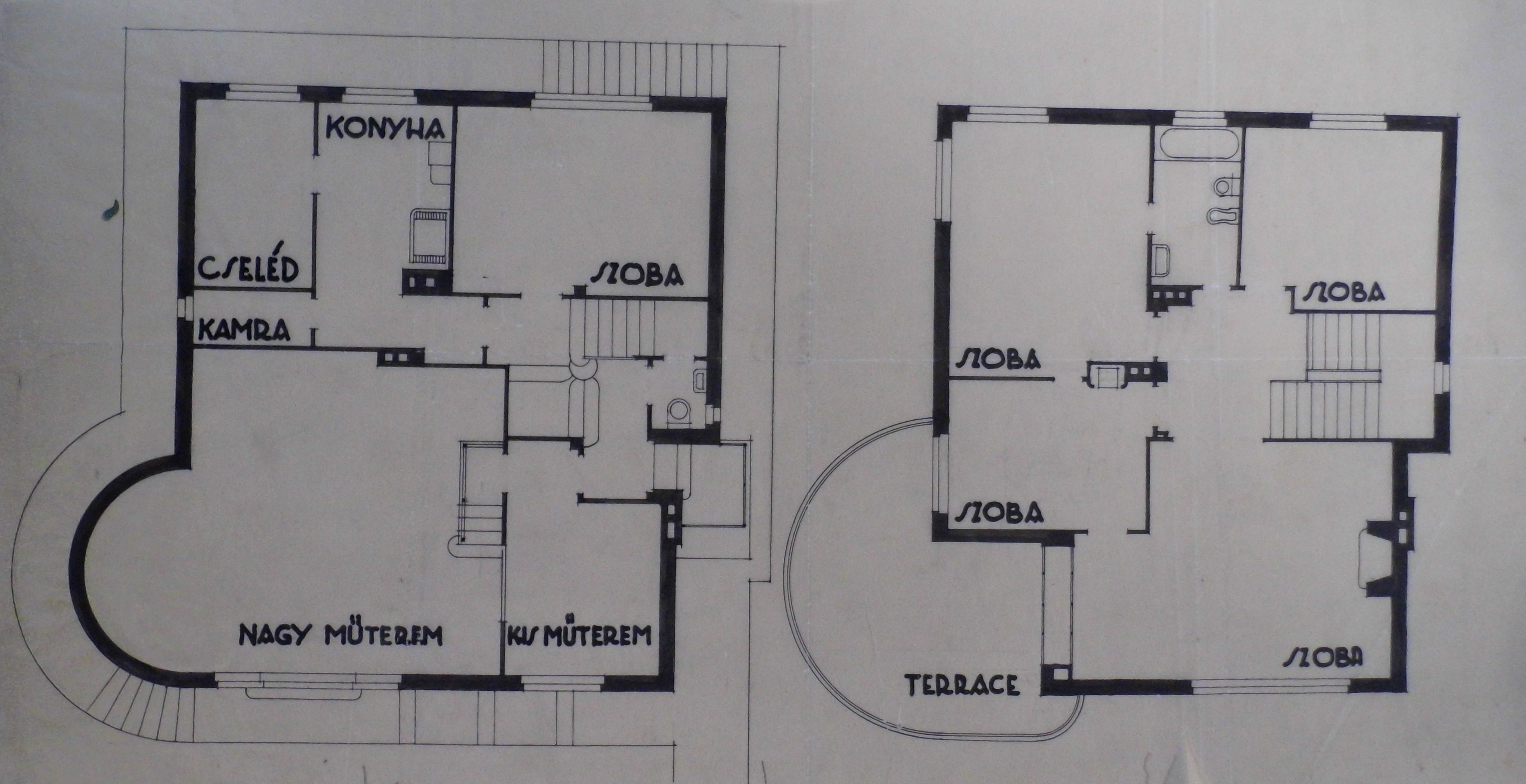

Floor plan of the villa on Ménesi Road (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

The entrance was created at the point of contact of the two blocks, at the bottom of a glass-walled staircase, through which light permeated. This was a key issue from the point of view of usability since light is essential for safe stair climbing. The large glass surface is strengthened by thin dividers, resulting in a grid pattern. The modern principles are also manifested in the fact that the main entrance is just a simple door that completely blends into this glass-walled mass. Usability and lightness were the guiding principles in the layout of the rental villa, so the rooms occupy the sunnier, southern half of both blocks, while the designer grouped the hallways, kitchens, and bathrooms in the northern part.

The entrance was on the courtyard side of the rental villa on Ménesi Road (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 8, 1932)

There are four rooms on the ground floor of the larger southern tract and three on the upper floor, while there are two rooms each on the ground floor and first floor of the northern block. Perhaps the excellent location of the building also justified the fact that a small studio flat was also created on top of the southern block. Only the southern has a basement, where, in addition to the garage, workshop and cellars, a flat was also furnished for the servant, who also worked in the laundry room at the top of the north block.

The Ménesi Road villa nowadays (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The facade is almost completely undecorated, the distribution of the windows is adapted to the function: on the south and west sides – to let as much light as possible into the rooms – there are ribboned windows that turn around corners, while the service rooms on the north and east sides only have smaller openings. The grille protecting the basement windows shows knowledge of one of the styles of modernism, the so-called streamlined style, as does the bent pipe railing of the semi-circular terrace. The interesting feature of the northern block was an arched opening with which the designer aimed to make modernism more Hungarian. Between the ground-floor windows of the Ménesi Road tract, a round relief was also visible, which depicted the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus (unfortunately, this was removed during later renovations).

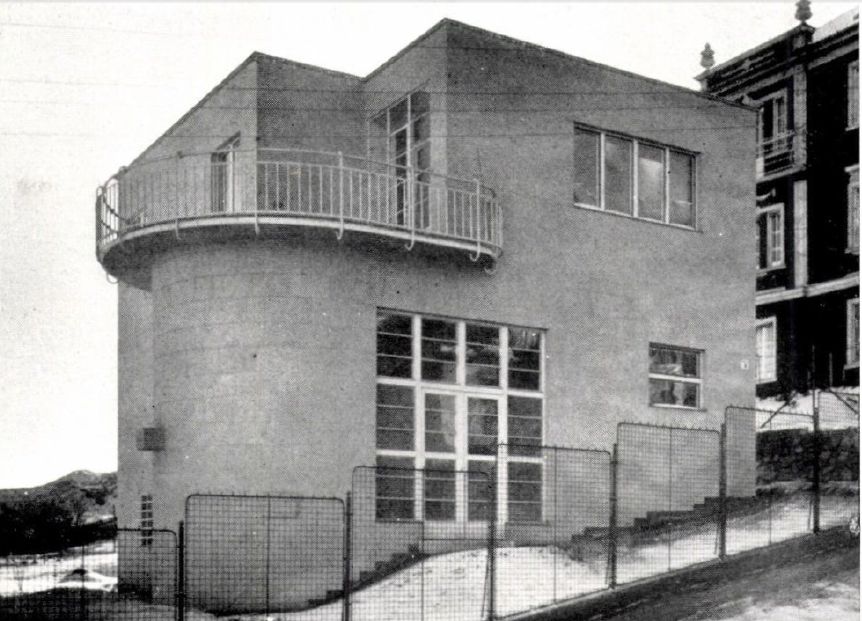

Gyula Tóth's studio villa at 8 Podolin Street (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 6, 1934)

In the past, Jenő Lechner gladly allowed painters and sculptors to appear in his buildings and – if only for the sake of this small decoration – he did the same in this modern rental villa. He maintained good relations with many of them, and in 1933 the sculptor Gyula Tóth commissioned him to design his villa, which included the studio. He also dreamed of a modern house under the steep 8 Podolin Street, which runs at the base of the Kiscelli forest park.

Floor plan of the villa on Podolin Street (Source: Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

It is also built up of elementary geometric shapes, of which the semicircular terrace extending from the north-eastern corner attracts the most attention. Otherwise, the villa's rather compact, small floor area is probably also explained by the terrain: Lechner wanted to avoid a large difference in levels within the building. He could not do it completely, but he put the slope to the service of the function: most of the lower east side is occupied by the studio, which could therefore be one and a half levels high. In order to shape the often large-scale sculptures, the high interior height was certainly necessary. In its continuation, on the western side, a smaller and lower studio was also located.

Huge windows provide light in the villa on Podolin Street (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 6, 1934)

Gyula Tóth's three-room and hall flat occupied the first floor, where the spacious dining room on the north side and the above-mentioned terrace opening from it increased the comfort. On the ground floor, in addition to the workshops, there was also the kitchen and the servant's room, and the additional service rooms (warehouse, laundry room, cellar) were located in the basement. The facade is once again dominated by the simplicity of modernism, and for the sake of light, a ribboned window opens on the wall of the dining room, which is the main communal room. Light also flows into the studio through a huge window, and because it faces north, it creates constant light conditions inside. The function was therefore also a priority in this villa, but aesthetics were also present, for example in the bent pipe railing of the semi-circular terrace. During the renovation in the 1960s, this was dismantled, as the terrace was surrounded by an iron-glass wall.

The villa on Podolin Street nowadays (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

No matter how practical the modern villas built between the two world wars were, the new owners often changed their interior layout as well. However, the simplicity of their external appearance suggests that good usability was the main guiding principle during their design.

Cover photo: The villa at 87 Ménesi Road (Source: Tér és Forma, Issue 8, 1932)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration