Pedestrians can use every bridge in Budapest, even the northern Újpest Railbridge (even the Connective Railway Bridge used to have a footpath, which has since been closed). Nevertheless, Budapest is not the city of footbridges. In fact, not a single pedestrian-only bridge exists over the Danube within the city limits, despite the need for one.

But what makes a bridge a footbridge? Something more than the fact that only pedestrians and possibly cyclists can cross them. Footbridges are public spaces, meeting spots, community areas. Recognising this function, several major cities worldwide have designed footbridges to fill this exact role.

The city centre and merchant hotspot: the Ponte Vecchio in Florence (Photo: Csaba Domonkos)

The city centre and merchant hotspot: the Ponte Vecchio in Florence (Photo: Csaba Domonkos)

Bridges have historically been meeting spots or even central elements of business life. Think of the old London Bridge, or Ponte Vecchio, or the Rialto Bridge.

In 2016, when Szabadság Bridge in Budapest was closed to vehicle and tram traffic due to the construction of the connecting tram network, a lively community formed on the bridge. Since then, we know it takes 1700 yoga mats to cover the entire bridge.

Road bridges, on the other hand, whether they are in a city centre or elsewhere, primarily serve to bring traffic across the river. They are, in essence, a type of road.

Budapest is missing a footbridge. The banks of the river are stunning, and people desire to be close to the water, from which they are currently barred. Many people believe that the Chain Bridge could be the footbridge of the future. However, the bridge was simply not designed to be one. It consists of three well-separated sections: the two footpaths and the road section. There is no way to move between the sections, and the view from the middle is lacklustre due to the nature of the design. Another solution is the only way forward to create a footbridge that so many in Budapest have wanted for years.

There are and always have been plans for a footbridge in Budapest. Even before the Chain Bridge was built, Tierney Clark recommended a footbridge. True, it could not have served to replace the Chain Bridge, only augment it.

Throughout the 19th century, plans were made for several footbridges. However, these were forced designs, planned as minimal solutions for spaces where larger bridges could not fit.

In the 1880s, the residents of pest increasingly demanded a bridge to connect the city centre with Buda Castle and the Tabán. However, a proper road bridge could not be built in the area due to the dense Pest city centre of the time.

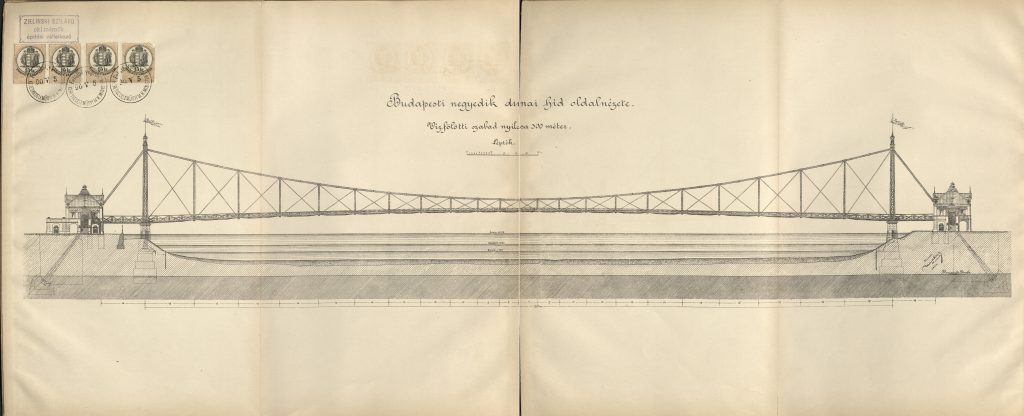

Thus, the plans of a unique bridge were made, which could be opened at the middle to shrink the size of the bridgehead on the Pest side, while two businessmen, György Gerenday and Adam Benicky, supported the construction of a footbridge. Szilárd Zielinski, a respected engineer of the era, drew up the plans for the bridge. The bold proposal merged design elements of suspension and beam bridges. Pedestrians would have used stairs to read the roadway on both sides, while trams would have been lifted with a crane.

Szilárd Zielinski’s plans for the footbridge, 1890. Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport. MMKM TEM 247

The other area where the idea of a pedestrian bridge was raised was the area around the Houses of Parliament. The grand structure was already in place when several specialists, including Lajos Lechner, the director of public construction at the time, raised the idea of a bridge in the area. In the Budapest Gazette (Fővárosi Közlöny) issuedon 14th April 1891 Lechner wrote:

“There will be need at some point, for the construction of a bridge near the new houses of parliament, however, this can only be built once the building has been completed.”

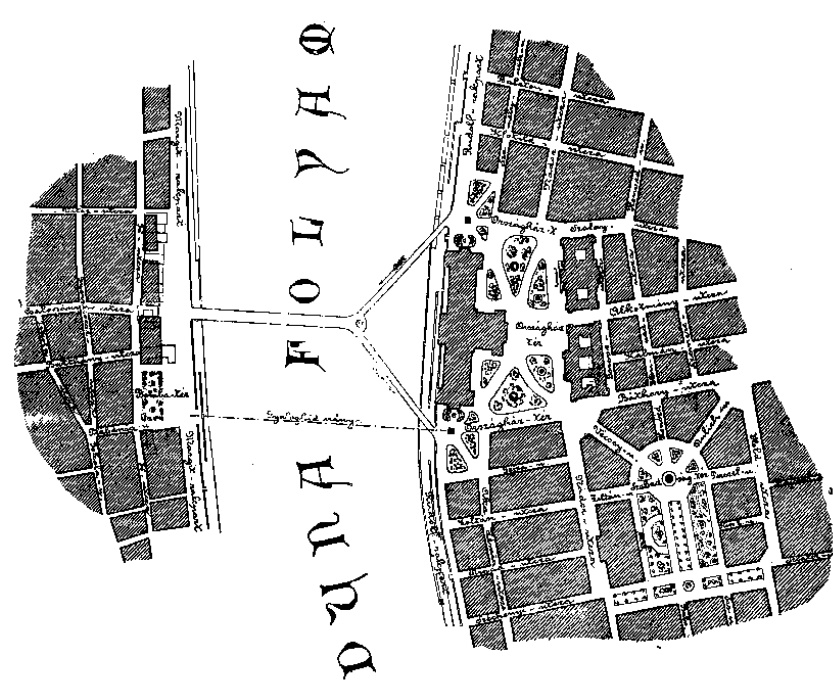

The bridge recommended by Ágost Lipthay, pedestrian section on the bottom, from Construction Industry, 26 February 1905.

After the turn of the century, once the parliament building had been completed, the question of a footbridge in the area was raised again, as the bridgeheads needed for a road bridge would have blocked the view of the stunning building. Writing in Construction Industry on 26 February 1905, Ágost Lipthay penned an interesting idea, planning not one but two bridges. The first was a footbridge starting around the Andrássy statue, on which moving walkways would have helped pedestrians climb the steep slopes. The other way a Y-shaped bridge, in which the two branches of the Y would have encompassed the Parliament.

The idea of a temporary footbridge was also raised when the Chain Bridge was closed between 1913 and 1915.

These original plans were never completed. A proper road bridge was constructed in the city-centre, sacrificing really all original building on the Pest-side. While near the Houses of Parliament, the temporary Kossuth Bridge was erected to replace the bridges destroyed during the Second World War. The bridges of Budapest were not particularly kind to pedestrians either. The footpaths on Chain Bridge were a recurring matter of contention. Pedestrians were only allowed to walk in one direction (on the right side of the direction of travel, similarly to vehicles). Thus pedestrians could not stop or turn around on the bridge. The strict rules stayed in place even when the bridge toll had been scrapped.

Following World War II, all bridges allowed pedestrians to cross, but this was not their primary purpose.

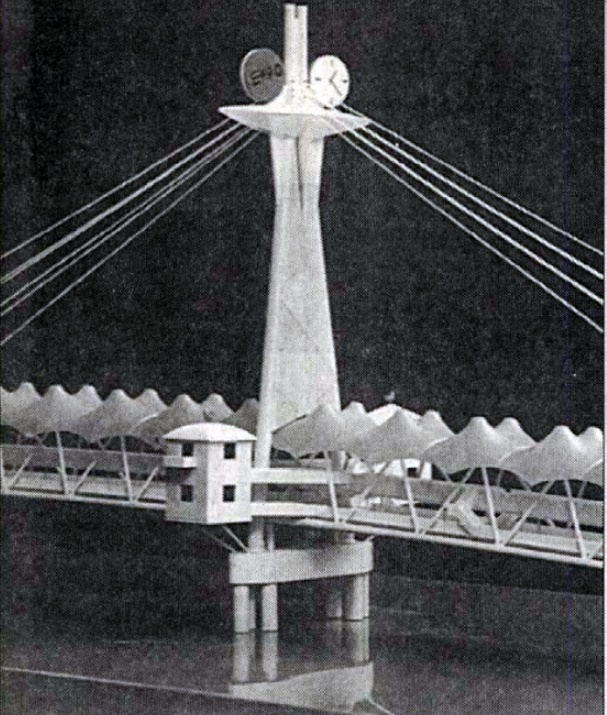

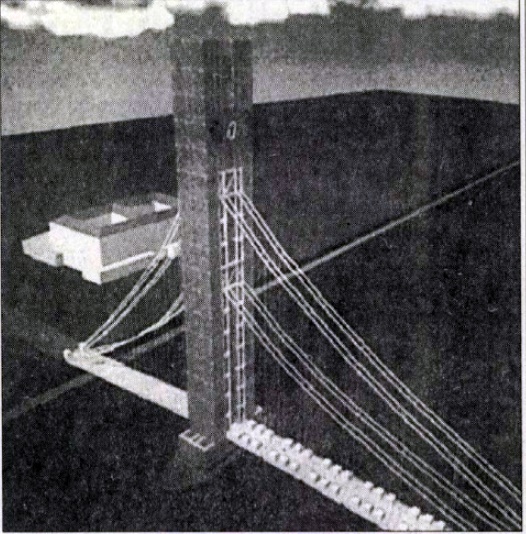

The first major plans for a Budapest footbridge were completed in connection with the 1995 Budapest–Vienna World Fair and then the 1996 Budapest Fair around Haller Street. The plans were created by the same UVATERV team that planned the Lágymányos Bridge, today is known as Rákóczi Bridge. This would also have been a temporary bridge to be deconstructed after the expo and rebuilt in another position as a road bridge.

A mock-up of the UVATERV bridge photographed in a newspaper (Photograph: Népszabadság, Budapest, Annex, 14 January 1994)

After the footbridge was never built for the cancelled World Fair, several pedestrian bridges were floated. Some were ideas. Others fully-fledged plans. Some were dreamt up by engineers, architects others by grassroots movements. Grass root and community pressure have long been a part of bridge-building in Budapest as the Chain Bridge, Margit Bridge, Szabadság Bridge were all first recommended and thought up by soldiers, investors and lawyers.

Another planned bridge from the middle of the 1990s was the Crytal Tower Bridge (Kristálytorony híd), created by the First Hungarian-Canadian Ltd. (Első Magyar-Kanadai Kft.). According to the plans, the bridge itself would have been a string of shops. The Budapest magazine of the daily Népszabadság wrote on 8 February 1994:

“Between Petőfi Bridge and the Connective Railway Bridge, the footbridge would be constructed in-line with Haller utca, connecting the two campuses of the University. The bridge would be a double chain bridge supported by the 150 metre (492 feet) high crystal tower placed 100 metres from the Buda side. The sights of Budapest would be visible from the floors of the tower, with 320 square metres per floor for shops, cafés and galleries in the glass tower.

The cancelled expo released the Genie from the lamp, and from the end of the 1990s onwards, several plans for pedestrian bridges were published. However, these were not designed to be agorae, rather shopping centres above the Danube.

József Finta and his office came up with several designs for southern Budapest, between the Petőfi and Rákóczi bridges. One of these would have spanned between the two university campuses around Haller Street. Another plan connected a footbridge to Rákóczi bridge, in essence hiding it from view. In 2019, he penned a plan for a seven-story house-bridge between Csepel and Albertfalva.

Foot and Cycle Bridge over the Danube. Budapest, between the Chain Bridge and Elizabeth Bridge – Design tender 1st place – 2005, lead architect: József Kószó (Source: 4 D Építész Stúdió)

Ideas coined after the turn of the millennium were the first to consider footbridges as public spaces, even designing two-levelled bridges with shops on the lower level and open spaces above.

In 2005 several architectural design competitions were announced regarding Budapest city-centre, and several studios, NGOs and private individuals entered with their ideas. These were all planned wither between Margit Bridge and the Chain Bridge or Chain Bridge and Elizabeth Bridge.

Those against these bridges claim that building a new bridge in these areas would disrupt the rhythm of bridges, the cityscape or even take up space from a needed “proper” road bridge. However, these locations have been raised several times in the past as well.

Architects also feel the need for a footbridge in Budapest. As a result, the designs entered for the design competition in 2018 for the new bridge planned in the area of Galvani Road considered pedestrians not side characters but focused on making crossing the bridge on foot or bike the most enjoyable as possible.

Hopefully, sometime in the near future, Budapest will gain an “agorabridge” that will spark a lively community life, just as Szabadság Bridge did when it was closed for a few weeks.

Cover photo: Pedestrians crossing Chain Bridge under strict rules: moving in one direction without stopping in 1894 (Source: Fortepan/Géza Fromm Dabasy)