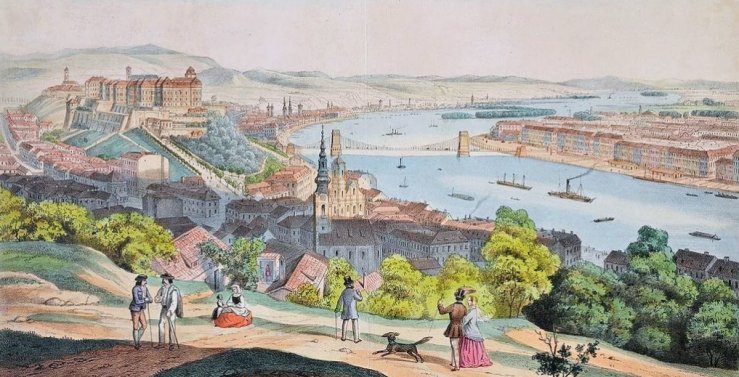

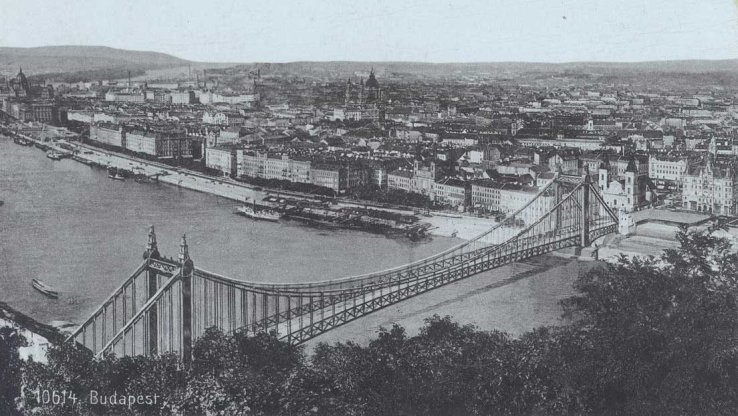

The first question about a permanent Pest–Buda bridge is why did this issue preoccupy the authorities when Vienna did well without a permanent bridge? The reason is to be found in geography. Buda and Pest are a city duplication that is not typical on the Danube. Vienna is actually on the right bank of the river, not on either side.

On the other hand, Buda and Pest are located opposite each other, not by chance, as this area was traditionally a crossing point on the Hungarian section of the Danube. This is why the Romans also built a bridge here. Even in the Middle Ages, it was one of the best ways to cross the river when travelling between Western Europe and the Balkans. The river is relatively narrow, its shores are not swampy, so it was ideal in all respects for a crossing.

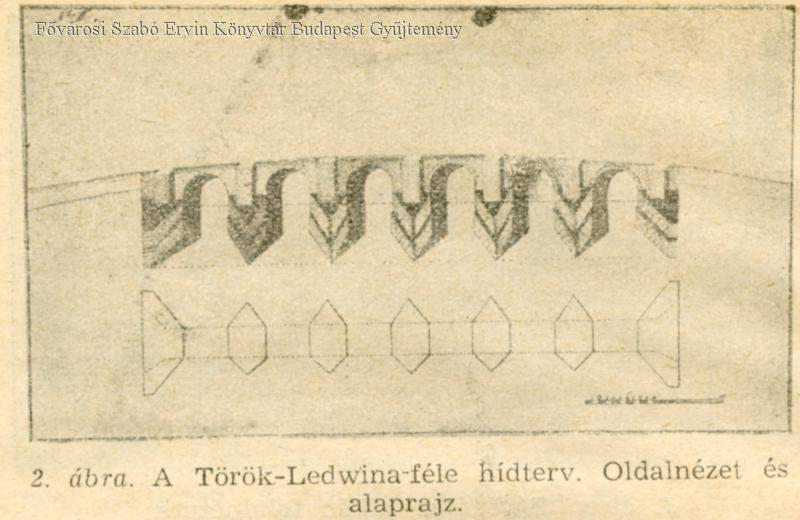

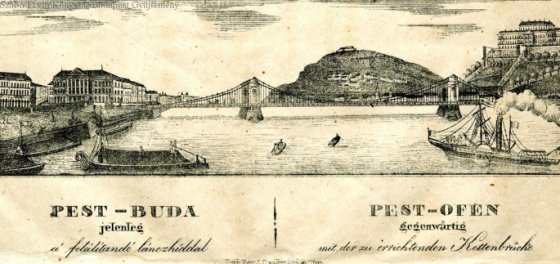

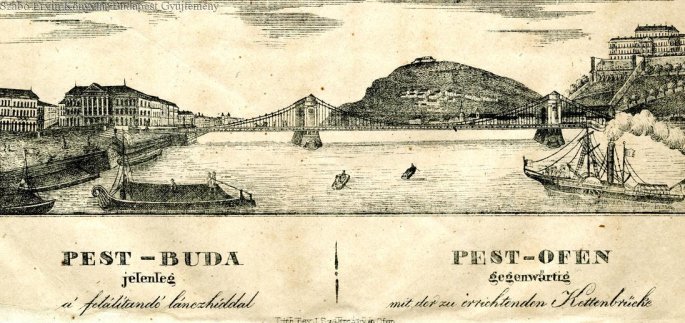

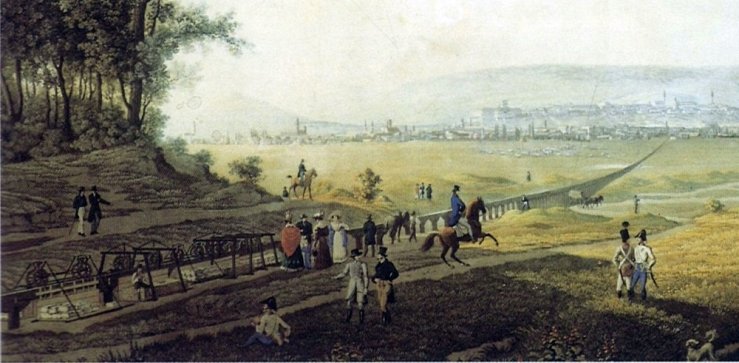

One of the first surviving bridge plans from 1786 (Török-Ledwina bridge plan) (Source: FSZEK)

There are also indications that at the end of the Middle Ages, both Sigismund and King Matthias thought of building a bridge. During and after the Ottoman Era, temporary structures, a pontoon bride and a reaction ferry opened up the crossing, but the commercial demand was so high that even Joseph II examined the possibility of building a permanent bridge. A few plans were up to the standards of the age, but when the officials of the Governor's Council examined the issue from a technical point of view in 1810, they rightly declared that no permanent bridge could be built between Buda and Pest.

At first glance, this may come as a surprise, as at the time, there were already particularly large bridges in many cities. Prague, London, Paris, Rome, and even Regensburg on the Danube, so why couldn't a bridge be built between Buda and Pest?

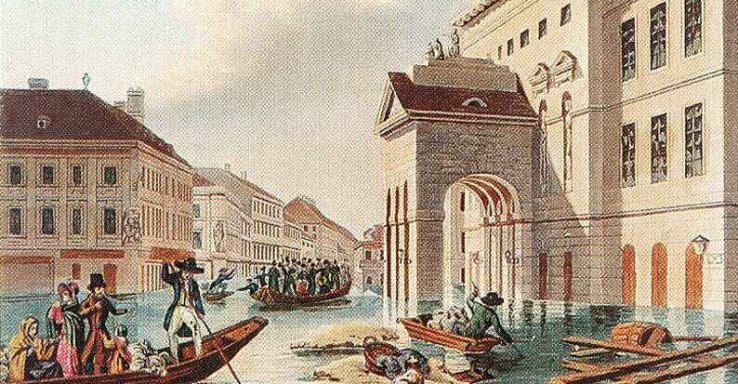

The reason was the Danube itself. On the one hand, the river (at least then) usually froze in the winter, and the ice flowed down the river in large boards, breaking and crushing everything in its path. On the other hand, the water flow of the Danube fluctuates. The difference between the highest and lowest water level ever measured at Budapest is 8 metres. Thirdly, the riverbed is sandy, which made the foundation work extremely complicated.

Nevertheless, even after 1810, many plans were made for the Pest-Buda bridge, the first by Antal Bernhard, who opened a crossing with his steamer 200 years ago. He received no substantive response to his plan in 1811, or at least no record of such has survived, but we know that he resubmitted it in February 1820 in almost unchanged form.

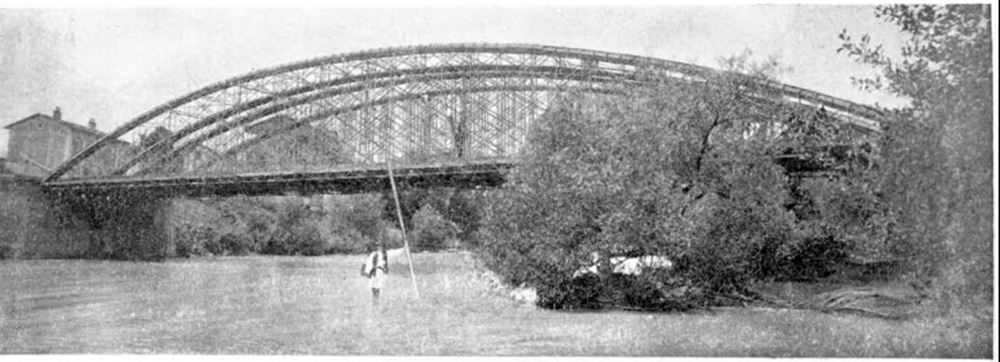

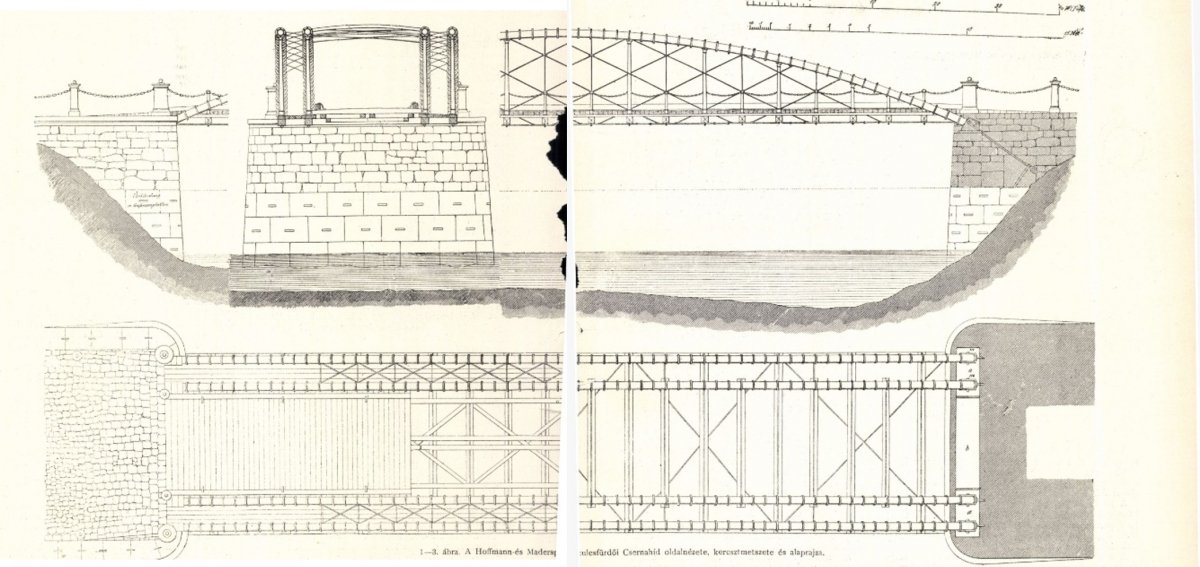

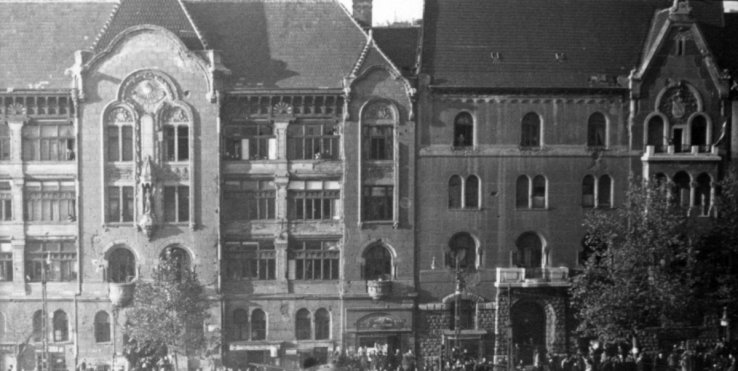

Contemporary (1842) tied-arch bridge in Karánsebes, built by Károly Maderspach, who put Bernhard's plan into practice (Photo: Magyar Mérnök és Épész Egylet Közlönye, No. 1, 1903, Róbert Totth: A karánsebesi régi Temes-híd)

According to the surviving documents (because no picture of the bridge survived), Bernhard proposed a revolutionary structure for the time, a tied-arch bridge.

As described in his submission, the Hungarian translation of which – the original language of the submission was German – is quoted in Imre Gáll's book Old Hungarian Bridges:

“The bridge consists of an arch connected to a "string" at both endpoints, on both banks of the riverbed. The "string" is connected to the arch by vertical suspension bares, secured with screws.

The arch cannot sink without bending the "strings" through the ordinates, thereby extending the entire length of the "string". The two cannot happen at the same time because one raises the other, making it impossible to bend the arch (…).”

What Bernhard described here is nothing else than a tied-arch bridge. The normal arch bridge had long been known, as it was based on an arch, but like arches, an arch bridge needs solid side support because otherwise, it will collapse. The chord between the two ends of the arch helps with this because, similarly to a bowstring, it holds together the two points of the arch at the bottom, preventing them from slipping apart.

.jpg)

One of the forerunners of tied-arch bridges, the bridge over the Aranyos stream (Torda) built at the beginning of the 19th century. A large model was displayed in the former Transport Museum (Photo: MMKM, inventory number: 10.69.5.1)

Today, it is a popular and frequently used bridge type, but it was revolutionary at the beginning of the 19th century. In Transylvania, similar wooden bridges were built in the 18th century, and Károly Maderspach also built similar steel bridges later, albeit at a smaller scale. The technical development of the structure was nowhere near far along enough for Bernhard's plan to be built in the 1820s.

Bernhard wanted to bridge the Danube with a single huge span and a very low curve that accounted for only 13 per cent of the bridge's total length. Imre Gáll, a bridge design engineer and bridge historian, writes about this project in his book quoted above:

“This idea is undoubtedly bold for the time but could be completed with today's state of the art technology with an arch height of 20% (the plans indicate 3%), albeit with a great deal of wasted material.

The bridge would truly have been feasible. There is one above the Danube, the size of which would correspond to the one sketched by Bernhard, the Pentele bridge at Dunaújváros. True, it was built in 2007 with 21st-century technology and was the largest bridge of the type in the world at the time. Bernhard also considered a multi-span structure to be conceivable in his submission but only suggested it as an alternative. The petition was rejected in 1820 by the Governor's Council on the technical proposal of the Directorate-General for Construction.

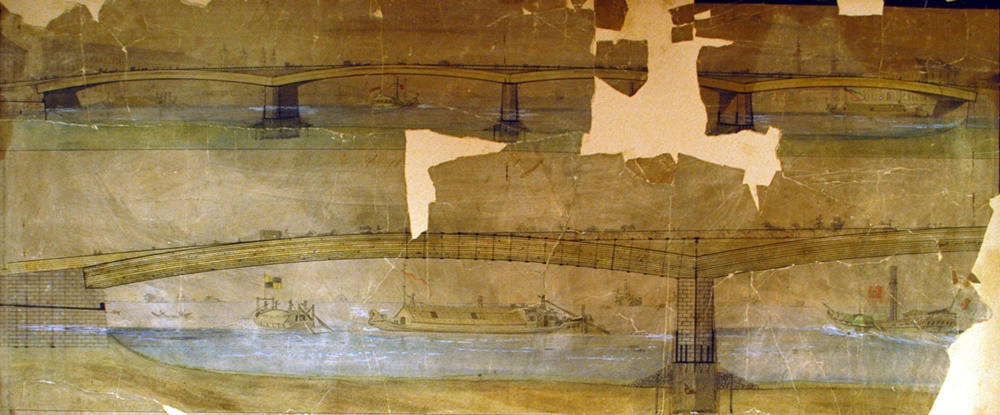

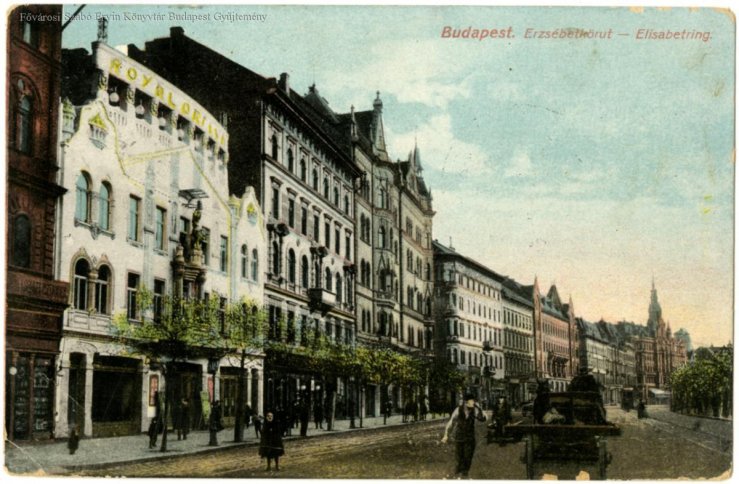

Another contemporary bridge plan: József Campmiller's design from 1819 (Source: MMKM Picture Collection Ltsz: 8014)

Although Bernhard's plan was rejected, various bridge designs appeared in the 1820s from well-meaning amateurs and highly trained engineers such as Pál Vásárhelyi.

However, at the time, there were probably 4–5 professionals in the world who could have built a bridge between Buda and Pest (not counting the almost insurmountable economic or political obstacles), some English, French or American engineers such as John Roebling, Mark and Isambard Kingdom Brunel and William Tierney Clark….

Cover photo: Kornél Zelovich: Maderspach and Hoffmann -type tied arch bridges (A Magyar Mérnök- és Építész-Egylet Közlönye, No. 2, 1903)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration