The Beautification Committee was established by Palatine Joseph in 1808 and tasked with urban planning. In the 200 years since, several Budapest development plans have been, including one in the 1910s, swept aside by history. Following World War I and the Treaty of Trianon, the world changed, and especially the role of Hungary and Budapest within it, its population, and their livelihoods. The Budapest Development Plan, adopted by the General Assembly of the Budapest City Council on 15 October 1940, was designed to adapt Budapest to these new challenges.

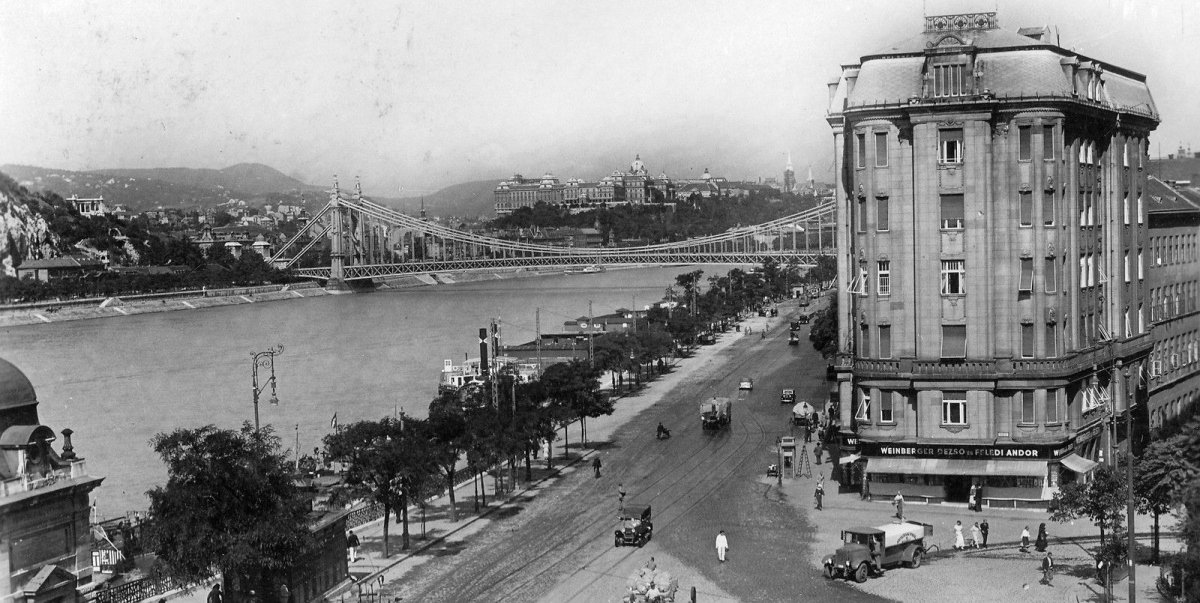

The Budapest cityscape in 1935 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 135104)

The Budapest cityscape in 1935 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 135104)

The 2 October 1940 issue of Pesti hírlap wrote about the plan:

"The new urban development plan aims to make better use of land in Budapest. (...) The primary and main goal of the development plan is to construction zones within the city that define to what degree different areas can be built up: the size of plots, houses, how many floors buildings can have, and what the ideal population density would be."

(The Hungarian text contains an error that cannot be translated into English. The word szépítési ['beautification'] is used instead of építési ['construction'] when referring to the created zones. It should be noted that the Hungarian name of the Beautification Committee set up in 1808 was Szépítő Bizottság – Trans.)

It would have been challenging to fit a detailed overview of the plans into a daily, as Ferenc Harrer wrote a 150-page study of it for the 1947/1 issue of the Tér és Forma journal. A massive amount of work stood behind the long study, as the committee formed to develop the plan had begun work eight years previously in 1932. The eight years had been spent with meaningful work.

A vast amount of preparatory materials were collected, including reports on the characteristics of the city's climate, its wind patterns, its hydrographic issues, the condition of its soil, and these were all taken into consideration during the planning phase.

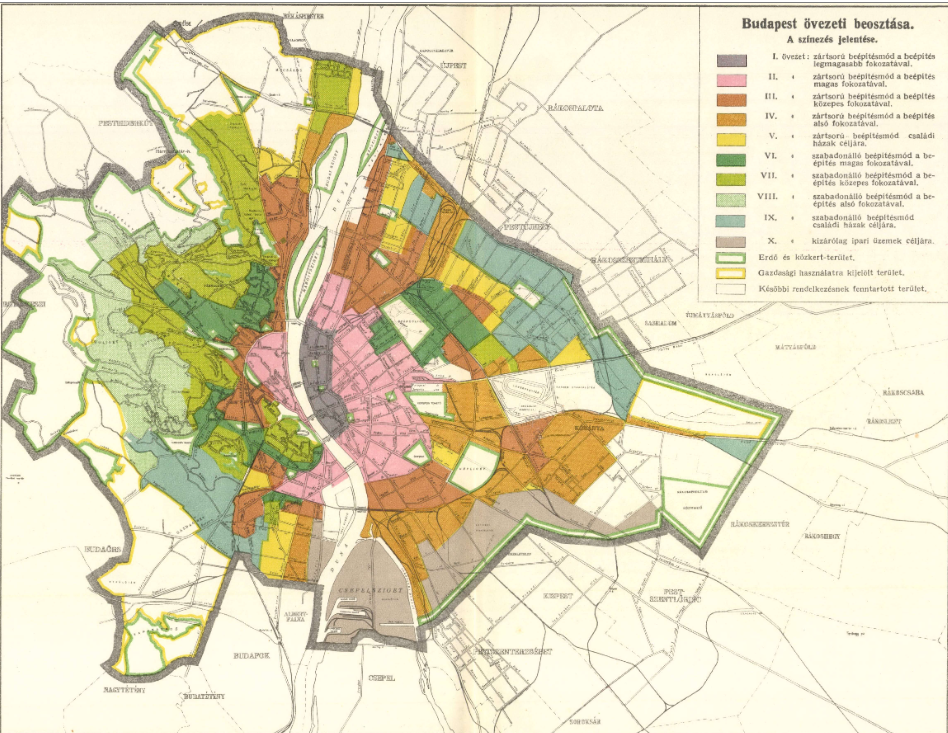

The new construction zones according to the 1940 plans (Városi Szemle, 1942, Ferenc Harrer: Budapest Construction Regulations, A study

The committee reviewed the functions of a modern city and examined how these could be achieved in Budapest to create a liveable city for all.

The city was divided into construction zones, from the densely built-up city centre to the outer residential areas with detached houses. Ferenc Harrer wrote of these in the 1941/1 issue of Tér és Forma:

"Each zone is defined by a single type of residential building, to ensure that only such buildings are built in the zone and achieve a uniform nature."

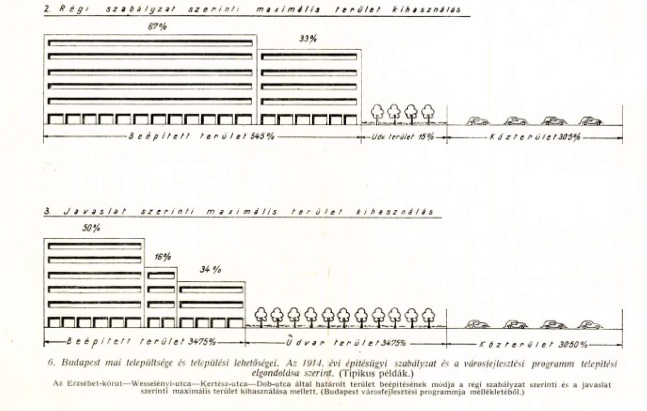

Among the new rules was one that broke with the tradition of inner courtyards. These had been popular at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. The courtyard or garden of the house could no longer be surrounded on all four sides.

The old and new regulations on buildings (Városok Lapja, 15 July 1940)

Toldy Ferenc Street and Donáti Street split in Víziváros, photographed in 1943 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 14978)

Toldy Ferenc Street and Donáti Street split in Víziváros, photographed in 1943 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 14978)

Of the densely built-up areas Harrer wrote:

"In accordance with the principle of concentration, and partly due to the situation at hand, the city centre is the most densely built-up area, and external centres have not been defined. This area on the Pest side is bordered by Aréna Road (present-day Dózsa György Road) – Orczy Road – Gróf Haller Road. In Buda, it is bordered by Horthy Miklós Road (present-day Bartók Béla Road), and Lenke (present-day Bocskai) Road and includes a part of Víziváros and the area of the Óbuda bridgehead."

The plan even contained provisions for tall buildings. Harrer even used the term skyscraper. Their construction was not to be limited to a small area, but an adequate number of parking spaces would have to be created around each.

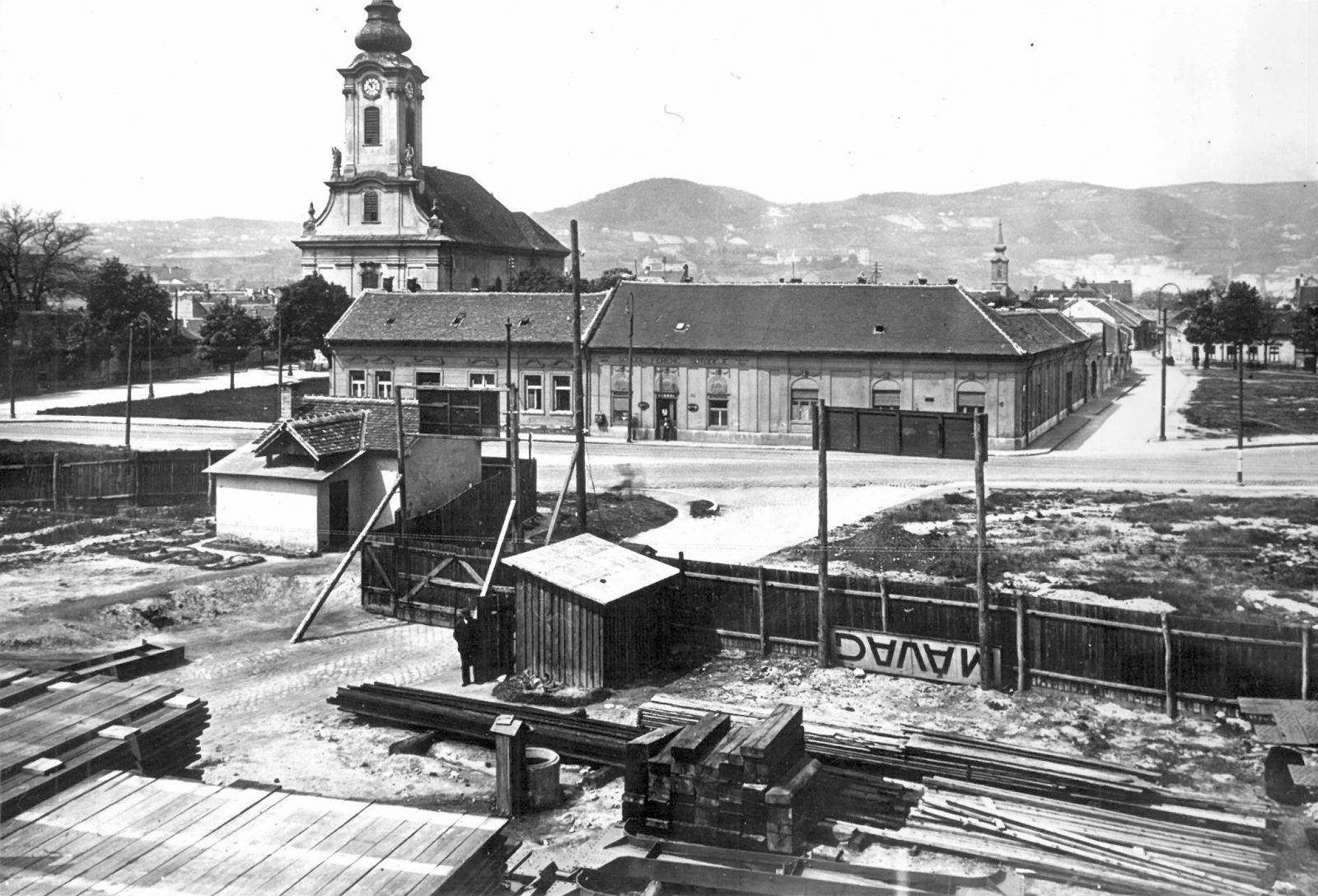

One of the designated city centres, the Óbuda bridgehead in 1944 (Photo: Fortepan, Magyar Királyi Légierő – Hungarian Royal Airforce)

One of the designated city centres, the Óbuda bridgehead in 1944 (Photo: Fortepan, Magyar Királyi Légierő – Hungarian Royal Airforce)

The goal was to build factories in locations that would minimalise the inconvenience caused to residents and even considered wind patters. Csepel, Kelenföld, southern Ferencváros, a the outskirts of Kőbánya ere chosen because of their proximity to waterways, and rail and road transport.

Óbuda photographed in 1940. The Church of Saint Peter and Paul can be seen on the left (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 116314)

Óbuda photographed in 1940. The Church of Saint Peter and Paul can be seen on the left (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 116314)

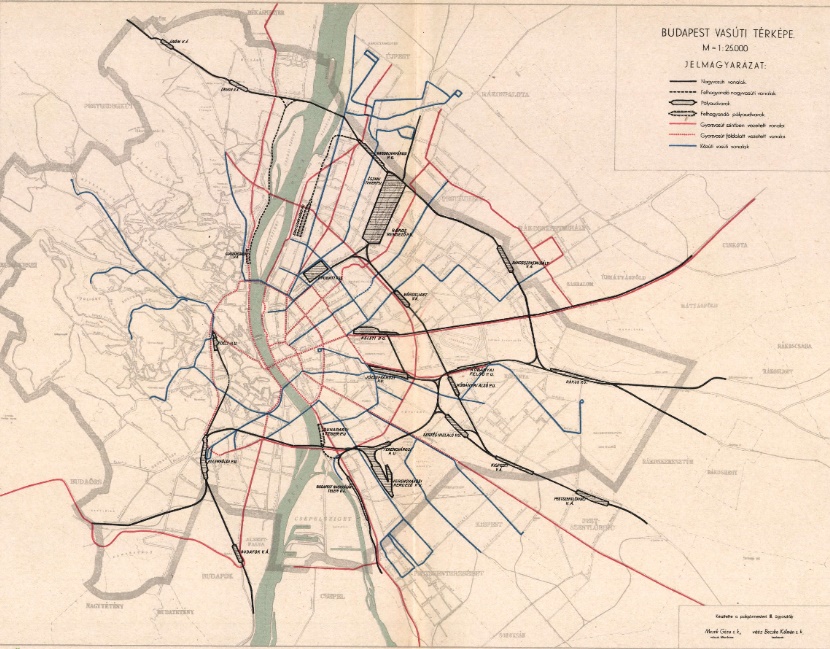

Transportation plans included the creation of main and national roads. The concept can be seen as a draft of what was realised in the 1950s, and even included the possibility of demolishing façades to achieve the required road width. The plans were completed two years before the Motorway Play by Boldizsár Vásárhelyi, which included the Budapest bypass. The concept designated the embankments as expressways for motor traffic.

Significant improvements to rail transportation were also planned, including the reconstruction of existing railway stations and the creation of a dense urban high-speed rail system, both above and below ground.

Rail network plan, dotted lines denote underground high-speed railway lines (Ferenc Harrer: Budapest Development programme, Városi Szemle, 1941)

However, the plan rejected plans for a navigable circular canal around the city.

Rwo interesting points highlight the mentality the concept. Of city parks Harrer's study says:

"In terms of groves, public gardens (city parks), or generally any small area the minimum needs of the population are not met in the most densely populated areas. Efforts must be made to create parks on the pest side which can serve for quick walks in the city."

Pozsonyi Road in the 13th District in the 1930s (FSZEK Budapest Collection)

As mentioned above the Óbuda bridgehead was designated as a high-density area. Nevertheless, the planners were aware of the fact that the site is littered with Roman ruins. On this subject, Harrer wrote:

"This process will likely bring even more Roman ruins to the surface. However, current results already indicate that the modern Óbuda will have to be built in line with the Roman Óbuda, which seems to be one of the most significant Central European ruins of the Roman world. The urban planning of Óbuda corresponds with that of the Roman city to a great degree, as is to be expected from both historical and natural characteristics. As a result, Roman ruins will be a natural part of Óbuda wherever they are found."

Large swathes of the plan were rewritten by history, the Second World War, the subsequent reconstruction and later the communist regime. Several elements of it, however, stood the test of time and influenced post-war plans. Nevertheless, it never accounted for forced industrialisation and large-scale prefabricated housing construction.

Cover photo: Fővám tér, looking towards Belgrád (Ferenc József) Embankment in 1935 (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 44838)

Dr Ferenc Harrer (Budapest 2 June 1874. – Budapest, 21 November 1969) urban planner, politician, university professor, Minister of Foreign Affairs between January and March 1919, member of the Budapest Public Works Committee between 1924 and 1942 and 1945 to 1949. The creator of the Greater Budapest concept. The representative for Budapest in the upper chamber of parliament 1934–1943. He did not quit politics after the Second World War and remained a member of parliament from 1949 until his death. In 1968 he received the Pro Urbe Prize.

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration