The architect, Béla Lajta, is the most influential figure of Jewish funerary art in Hungary. At the beginning of the 20th century, he designed several tombs for several of the leading Jewish families in Budapest. Many of them can still be seen and visited today in the Jewish cemeteries on Kozma Street and Salgotarjáni Street. Early examples of his funerary art show characteristics of art nouveau, while his later works were influenced by early art deco.

A designer of synagogues

Béla Lajta was born in Budapest as Béla Leitersdorfer in 1873. His father, Dávid Leitersdorfer (1838–1920) was a tailor and leading figure in the Pest Israelite Community. In 1899 he was a high ranking figure in the Chevra, the burial society. Similarly to his father, the young architect took an active role in the work of the Chevra Kadisha in Pest from the end of the 1890s. His official stamp read: "Leitersdorfer Béla építő, az Izr. Szent Egylet Műszaki Tanácsadója" ('Béla Leitersdorfer, architect, Technical Consultant of the Isr. Sacred Society"). He changed his name to a more Hungarian form in 1907.

Béla Lajta (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 15 October 1911)

The size of the Jewish community in Pest and their wealth increased drastically by the end of the 19th century. On major holidays, even the two-storey gallery of the synagogue on Dohány Street proved to be too small. The community was forced to lease several empty shops in various parts of the city, especially in Lipótváros, for ceremonies that attracted a large number of faithful.

To solve the problem raised, the congregation issued a design tender for a monumental synagogue. The submitted and ranked plans all significantly exceeded the planned budget. The new sacred building was at the time to be built in the 5th District, not far from the parliament building, which was still under construction, on a plot bordered by Szalay, Szemere, Koháry – present-day Nagy Ignác – and Markó Streets.

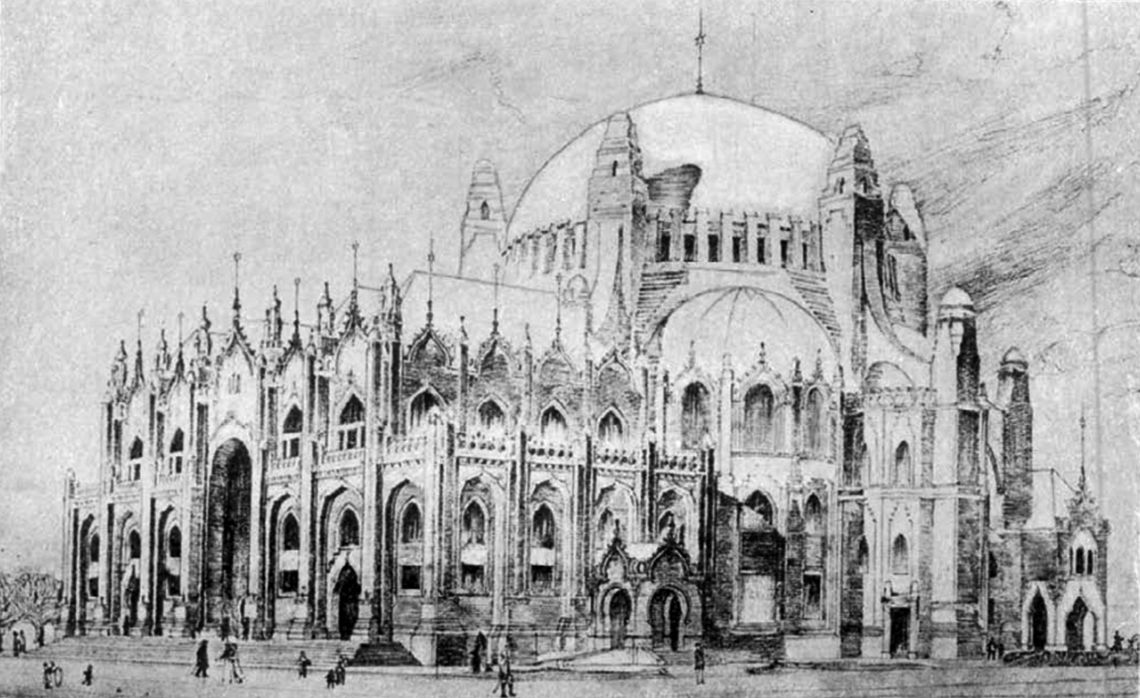

Béla Lajta's plan in Vasárnapi Ujság

Béla Lajta relied on the six-pointed star in his design for the 1899 synagogue tender. He even used the term "drawn hexagram as an architectural symbol" as his pseudonym for the process. He believed that 60-degree angles were the perfect solution to distributing the mass of such a large synagogue and ensuring the building remained proportional.

The judges ranked Lajta's design third. However, due to its extremely high costs, the winning entry by Ernő Foerk was never built either.

The most popular weekly at the end of the 19th century, Vasárnapi Ujság, presented Lajta's design with the following words in its 26 march 1899 issue: "third place was awarded to the design by the architect Leitersdorfer, in which even the smallest details conform to the rules of Oriental-style architecture. Both sides of the domed main building are lined with six towers that end in the frusta of pyramids. Between these four flat-roofed side buildings attach to the main structure, to expand the interior with further space for benches. On the facade facing Markó Street, a side structure with an arabesque dome protrudes with a large open arch for the main entrance. A second main entrance protrudes symmetrically on the rear, as well as side-doors on either side. The windows and ledges of the building are defined by Arabesque and Moorish ornaments, but not overcrowded. The plan is artistic in nature, and all pillar-like supports are foregone by the design.

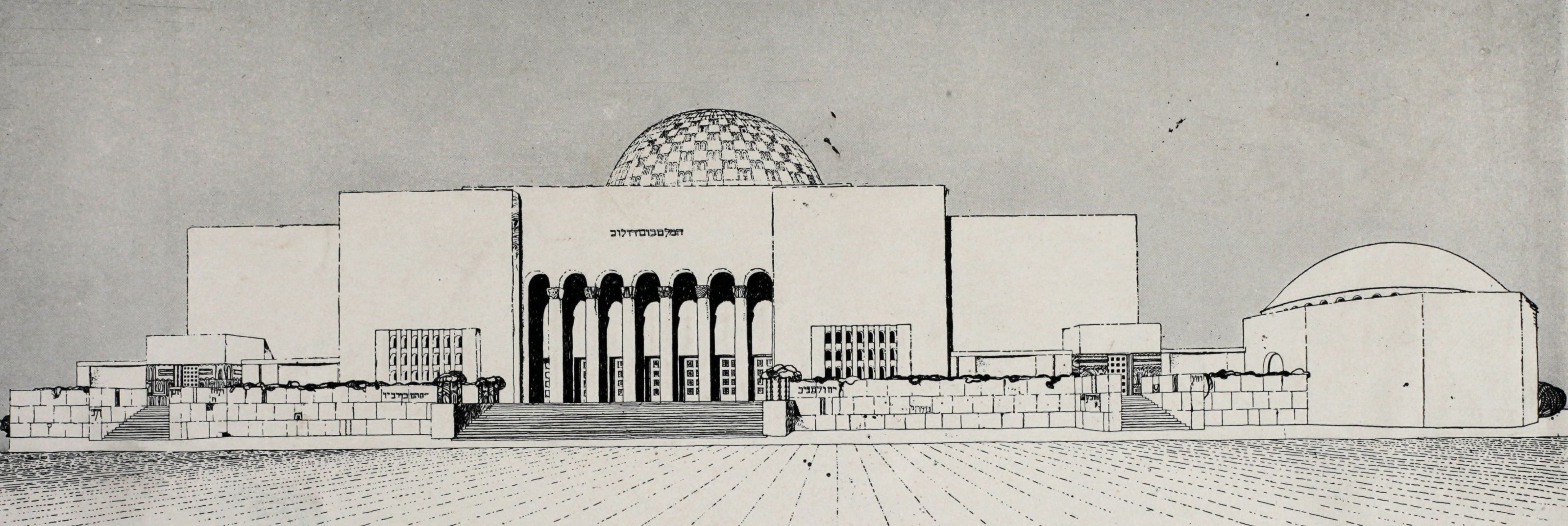

The synagogue planned for Buda, 1912

In 1912 Béla Lajta's design for a synagogue to be erected in Buda on Krisztina Boulevard near Széll Kálmán Square was awarded first place on a design tender. The architect envisioned a large domed space for major holidays and a separate, smaller space for more everyday prayers. The design can be considered a forerunner of 20th-century design, as it was dominated by simple surfaces, with ornamentation concentrated in a single area. The synagogue was never built due to the changing winds of history.

His work in the Jewish cemetery on Salgótarjáni Street

In Béla Lajta's oeuvre brick, ceramic, and stone surfaces offered a pathway to a unique artistic expression. An idiosyncratic style that was in line with the most modern currents of European architecture at the time. The thirty-five tombs and memorials designed by Béla Lajta offer a detailed overview of the variations in his work.

The Jewish cemetery on Lehel Road had been filled in the 1870s. The Jewish Congregation of Pest founded a new cemetery on Sajgótarjáni Street, not far from the national cemetery on Fiúmei Road. In a few decades, the new Jewish cemetery became the resting place of residents and entrepreneurs who accelerated the development of Budapest into a metropolis, and who commissioned considerable tombs for themselves and their families.

Béla Lajta designed not only tombs in the cemetery but the entrance and ceremonial buildings. The ceremonial building was built with a domed roof covered with Zsolnay-ceramic tiles. Due to poor maintenance, the roof collapsed in the 1960s, and the Zsolnay tiles were destroyed.

The tomb of József Bródy and his family stands out among those created by Béla Lajta in the Salgótarjáni Street cemetery in both artistic formation and the use of materials. The tomb, built in 1907, evokes the layout of ancient and early mediaeval round churches simultaneously. The historian of architecture, Rudolf Klein, considered the design a unique interpretation of the ancient tradition. The wealth of the deceased József Bródy is indicated by the materials used, which include Swedish granite.

The forms of late Viennese art nouveau, the Wiener Werstätte, can be seen on the tomb designed for Emil Guttman's family. Lajta's design is compact. The pedestal is topped with a half-a-metre thick and two-metre tall arched stone wall. Two geometric lion heads were carved on either side of the tomb.

By designing the grave of Rabbi Dr Vilmos Bacher (1850–1913) as a stele, Lajta returned to the centuries-old tradition of Jewish tombstones. The white marble stele is decorated with carved vines growing in two directions from a flower pot. A copy of the monument made of cast stone was erected by Lajta's family, as Henrik Lajta's (1865-1921) tombstone, in the Jewish cemetery on Kozma Street.

The Tomb of Henrik Lajta was completed in 1921 (photo: Máté Millisits/pestbuda.hu)

Lajta's work in the Jewish cemetery on Kozma Street

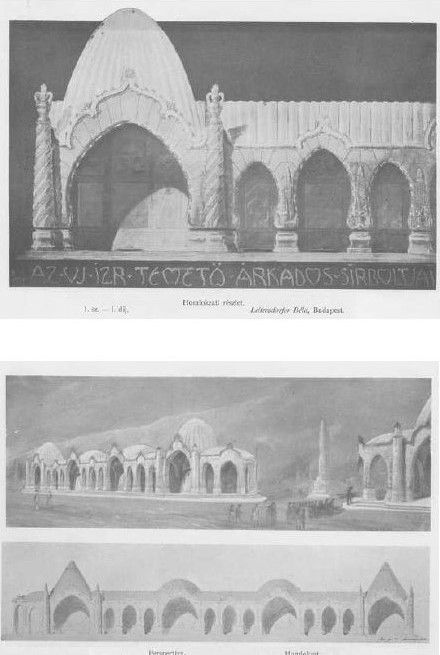

Two decades after the Salgótarjáni Street Cemetery was opened, it was deemed too small, and the community opened a new, significantly larger cemetery in 1891 in Kőbánya, on Kozma Street. The large ceremonial building at the entrance was built according to the plans of William Freud. Béla Lajta designed the burial arcade nearby in 1903. Lajta would have made the design more dynamic by modulating the size of the arches, but his design was not implemented.

Burial arcade in the Kozma Street Cemetery

The lawyer, Miklós Schmidl, commissioned a tomb for his parents Sándor Schmidl and his wife, Róza Holländer, grocers in colonial goods, in 1902 and 1903.

Béla Lajta's design combines archaic, ancient culture, with Jewish and Hungarian folk art in a ceremonial fashion, emphasising the artistic possibilities in ceramics and mosaics. The ceramics were created by the Zsolnay factory in Pécs, while Miksa Róth's workshop provided the mosaics. Leaning against the cemetery wall, the grave stands unsupported from the sides and is dominated by arch-supported walls.

The tomb designed for the Schmidl family (Photo: Máté Millisits/pestbuda.hu)

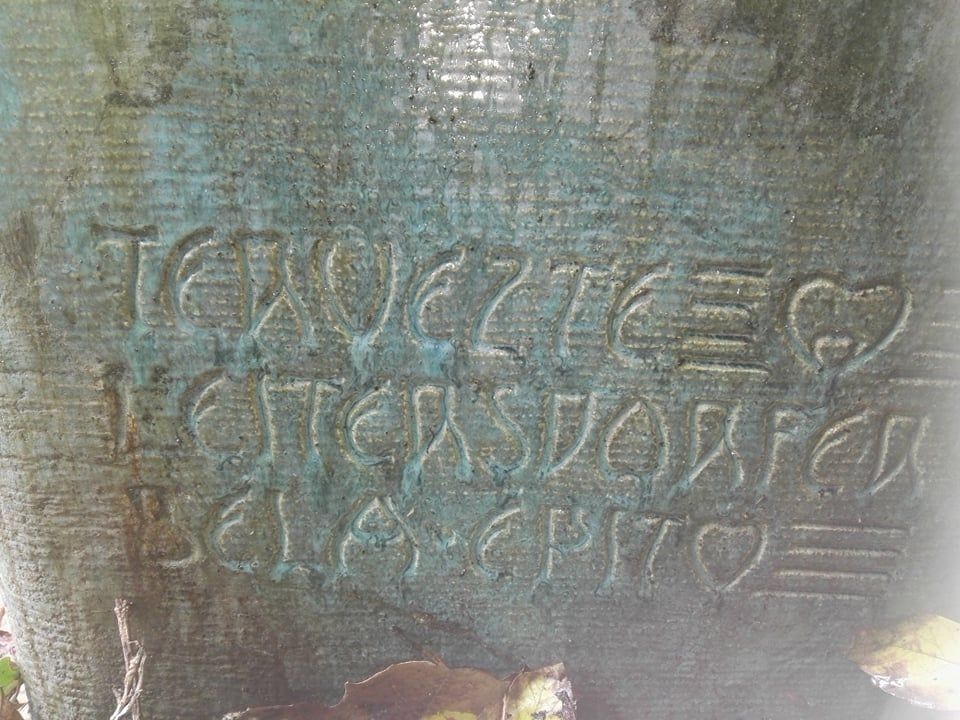

A crypt was built under the rectangular vault. Twenty-five large Zsolnay ceramic tiles dominate the main facade, the size of these is emphasised by the enveloping form and the cement between them. A signature on one of the ceramic elements reads Béla Leitersdorfer, architect.

"Designed by Béla Leitersdorfer builder" - reads on one of the ceramics (photo: Máté Millisits/pestbuda. hu)

Turquoise majolica-glazed Zsolnay-ceramics coat the facade of the Tomb (photo: Máté Millisits/pestbuda.hu)

The top of the main facade is decorated by a six-petaled plant ornament, reminiscent of a Star of David. A winged wrought-iron gate serves as the entrance to the crypt. The doors are an art nouveau masterpiece, a tree trunk from which the branches of a willow tree stream downwards.

A yellowish-white rose is visible at the bottom of the heart-shaped, indented mosaic surface, which is part of the "braided" Zsolnay ceramic basket, which rises out below it.

A Zsolnay-ceramic basket decorates the gate (Photo: Millisits Máté/pestbuda. hu)

The Schmidl tomb is related to the interior atmosphere of the 5th-century mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, but the elegant industrial design is also reminiscent of the entrances to the underground railway on Andrássy Avenue designed by Albert Schickedanz. The two buildings differed in their function and artistic style but shared an external covering composed of entirely Zsolnay-ceramics.

The National Pantheon Foundation restored the Schmidl tomb in 1998. The architects Tamás Kőnig and Péter Wagner, the art historian Ferenc Dávid, and the restorer Klára Csáky worked on the project.

The Gries tomb is another prominent monument designed by LAjta in the Kozma Street Cemetery. The exterior of the Gries-mausoleum was originally completely covered with Zsolnay-ceramics. The roof of the dome was made of pale green ceramic tiles playing into ochre. A line of geometric ornamentation decorates the arched entry.

The Gries Tomb (Photo: Millisits Máté/pestbuda.hu)

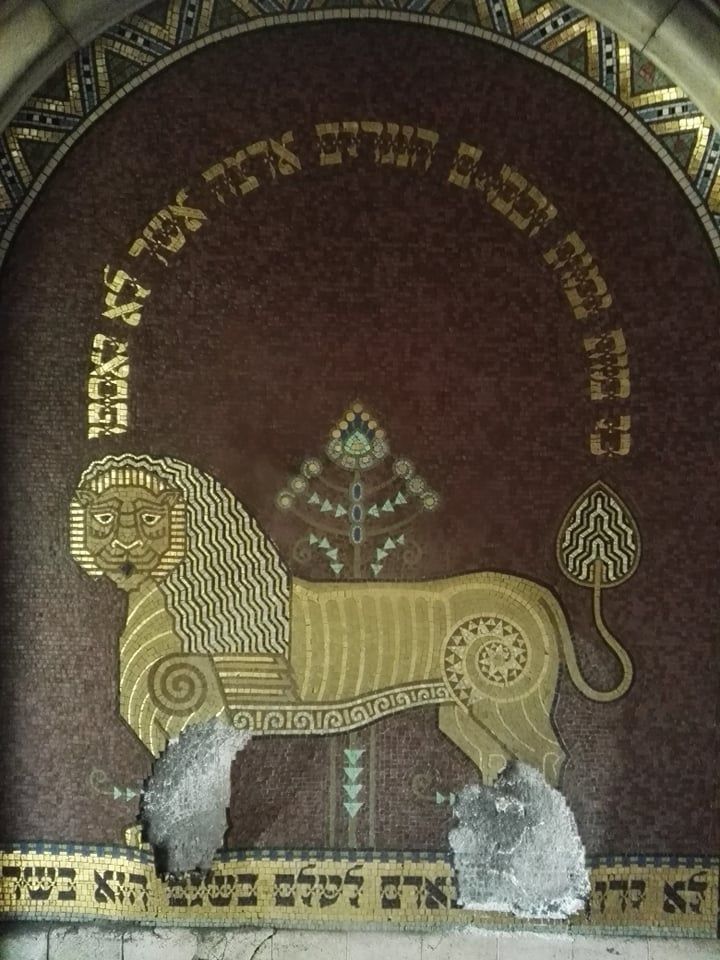

Gold and blue are the main colours of the mosaic on the inside of the Gries-mausoleum and empower the artistic representation of creation and rebirth.

Gold and blue mosaics decorate the interior of the Gries-mausoleum (Photo: Máté Millisits/pestbuda.hu)

The lion motif inside the Tomb (Photo: Máté Millisits/pestbuda.hu)

The mausoleum currently stands neglected and unmaintained, however, should be restored because of its artistic value.

Béla Lajta died in Vienna on 1 October 1920. His grave can also be found in the Kozma Street Cemetery. Designed by Lajos Kozma, the elegant tomb stands as a fitting memorial to the aesthetic values created in

Cover photo: The Schmidl family grave (Photo: Máté Millisits/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration