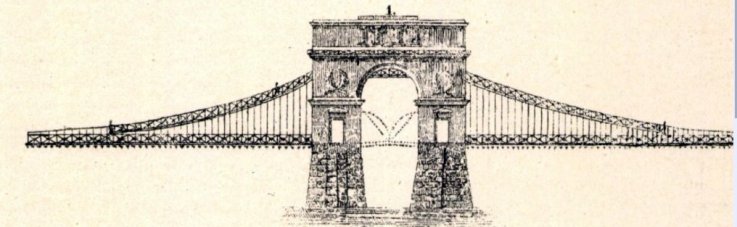

Chain Bridge is the most important Bridge in Budapest and Hungary. István Széchenyi’s dream and William Tierney Clark’s plan came to life was realised through funding provided by György Sina, when one of the largest and most modern bridges in the world at the time opened in 1849. The bridge was rebuilt between 1913-15 according to the plans of Hungarian engineers and also rebuilt with their sacrificial work after the Second World War, in which retreating German troops blew it up.

When was it named?

The structure’s official name is Széchenyi Chain Bridge. Kossuth proposed the name as early as 1842, and in 1895 a movement was started to rename the bridge, which was resisted by the Ministry of finance which had oversight over the bridge. Until 1915 the bridge did not even have a name; it was simply known as the lower case “chain bridge.” It was eventually given its current name in 1915.

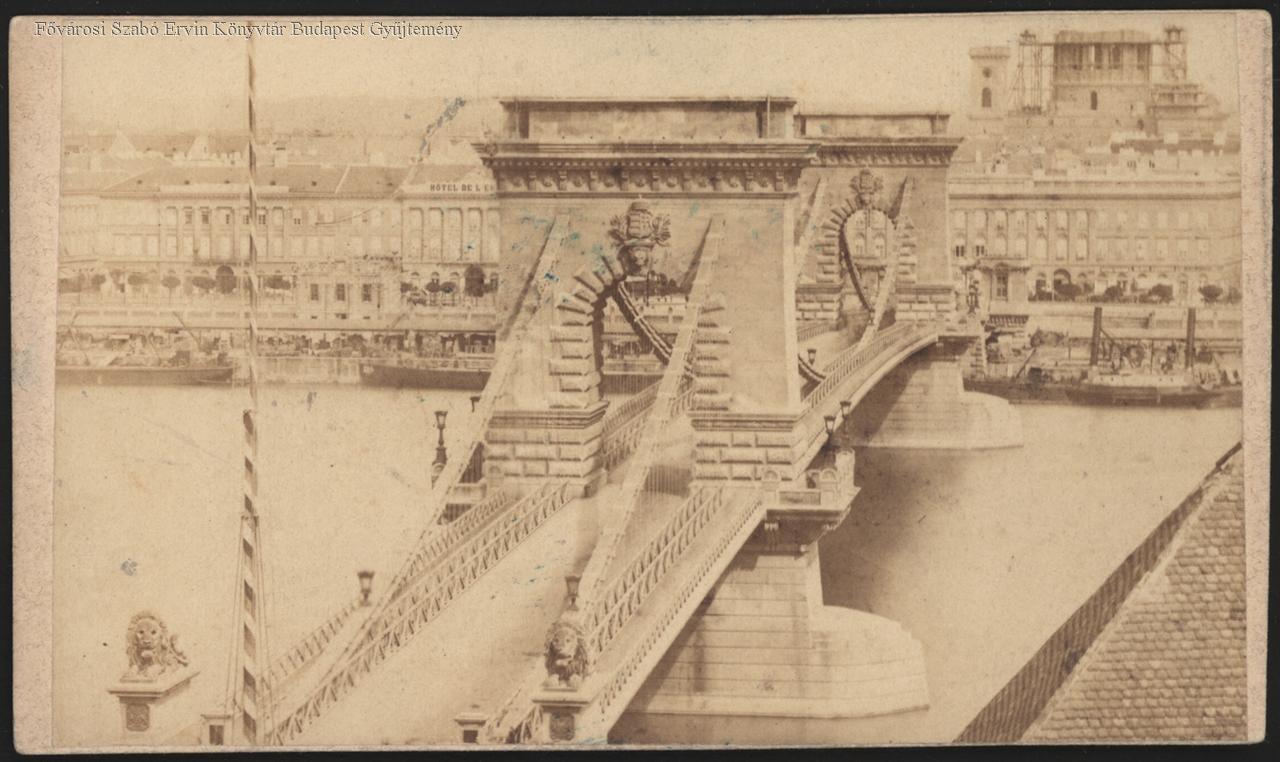

One of the earliest photographs of the Chain Bridge, taken between 1860–1865 (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

When was the bridge built?

The current bridge was built between 1947–1949 according to the plans used for the 1913–1915 reconstruction. More than 70% of the old chains could be reused during the reconstruction after World War II. The remaining iron was newly forged, while the pillars and bridgeheads were repaired.

Which parts of the original bridge have survived since 1849? The foundations and bottom of the pillars have not changed over time; everything else has undergone major or minor modification over the last 171 years. The biggest changes happened during the restoration in 1913–1915, and the post-World War II reconstruction.

This picture from around 1900 depicts the original bridge. The visible change in the pavement highlights the transition between stone and wooden cubes. The original bridge was paved with wooden cubes, which had to be maintained regularly (Photo: Géza Dabasy Fromm/Fortepan/No.: 93392)

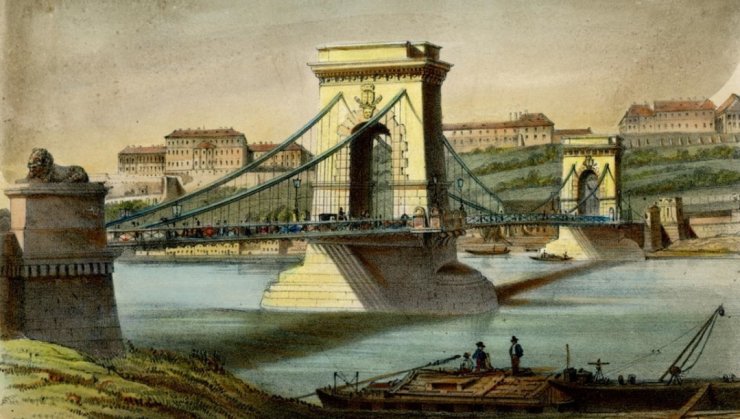

Is it really a copy of a bridge in England?

No. The designer, William Tierney Clark, planned several bridges in England, one of which has survived more or less unchanged, the bridge over the Thames in Marlowe. Since they were designed by the same engineer, there are several structural and aesthetic similarities between the two bridges.

Do the lions have tongues?

Yes. The legend that during the opening ceremony, a spectator shouted “look, the lions have no tongues!”, resulting in the sculptor’s, Marschalkó’s, suicide, is false. In fact, it is a borrowing of an Austrian story, according to which during the unveiling of an equestrian statue in Austria someone exclaimed that there was no stirrup on the saddle.

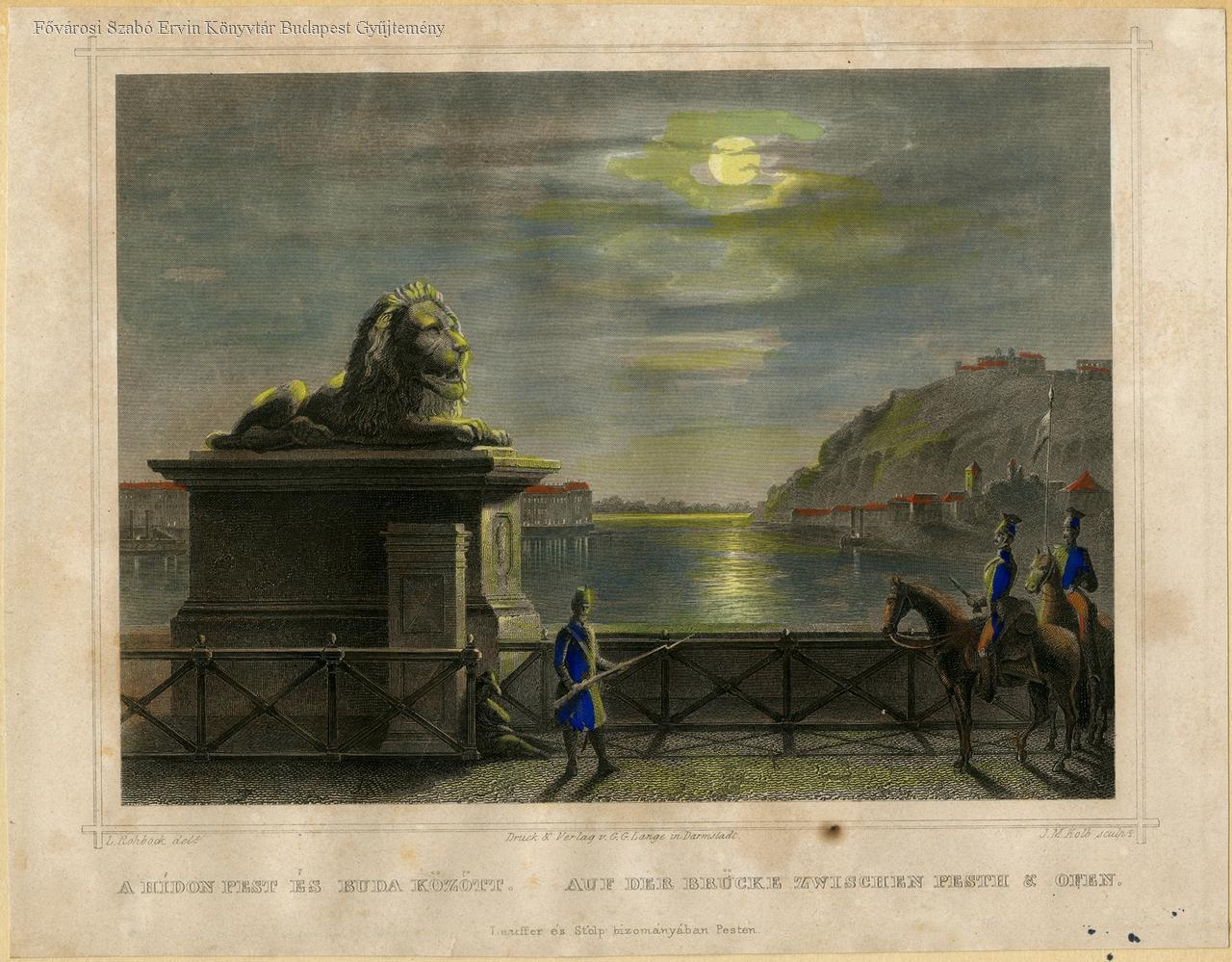

The lions on a mid-1850s engraving by Ludwig Rohbock (Photo: FSZEK, Budapest Collection)

Were the lions added to the bridge later?

No. Another reason why the anecdote above is untrue – there was no separate unveiling. According to contemporary newspapers, the lions were on the bridge when it opened. Moreover, according to Miklós Barabás (who spent a lot of time with the builders of the bridge), the sculptures were originally placed facing the long direction, looking towards the centre of the river. When Tierney Clark visited in the autumn of 1849, he was furious and had them switched.

What was added to the bridge later?

The coats of arms of the Sina and Széchenyi families. These were also created in the Marschalkó workshop in 1852 (and may be the root of the legends above). Later, gas lighting was also added as were the inscriptions about the bridge’s history.

Was it illegal to build another bridge next to Chain Bridge?

Many people claim that no other bridge could be built on the Danube within a mile of Chain Bridge in either direction. This is partly true. The company that built the bridge, the Chain Bridge Company, had an exclusive right to build a bridge between the two cities and collect a toll for crossing. However, the real distance protected was shorter than a mile (a Viennese mile being 7,585.92 metres, and a Hungarian mile 8,353.6 metres). The restriction extended to the edges of the cities on the river bank, which were all closer to Chain Bridge than 7.5 kilometres. In reality, this exclusive deal was not cast in stone: in 1865 a private individual received permission from the emperor to build a bridge. Maygraber Ágáston wanted to build a railway bridge on the site of today’s Margaret Bridge. (Later, it turned out he had neither money nor a good plan, and the permit was revoked in 1868). Nevertheless, he would have had to collect a toll and pay the Chain Bridge Company after each crossing, just as the operators of small ferries and boats paid a toll on their passengers to the Chain Bridge Company. The one-mile protection was presumably pushed by the Chain Bridge Company itself, to deter investors from building new bridges.

What was its colour?

The bridge has always been grey but has been coated in various shades. It was repainted regularly in the 19th century and saw coats of light grey, yellowish-grey, pigeon grey and dark grey.

The bridge was always grey. The pavement on the original bridge was 40 centimetres narrower. Pedestrians were only allowed to walk in one direction until (Photo: Both Balázs / pestbuda.hu)

Are cyclists allowed to use the bridge?

Cyclists have been allowed on the bridge since August 2012. Before then cyclists had been barred from using the bridge except for during a few exceptional periods.

A few more interesting tidbits.

Until 1937, pedestrians were required to move in a single direction on the bridge: on the right-hand side pavement in the direction of travel – even though at the time road traffic would still use left-hand traffic rules. Stopping or turning around was against the rules.

The bridge was privately owned until 1870; its shares were listed on the Vienna Stock Exchange, meaning virtually anyone could have bought it. True, the price would have been high. When the state bought the bridge, it paid nearly one and a half times as much as the construction of Margaret Bridge had cost.

One of the most beautiful bridges in the world, a symbol of Budapest, is in a rather bad shape (Photo: Both Balázs / pestbuda.hu)

In 1896, one of the captains of the Danube Steamship Company (DGT, or more commonly, based on the German name, DDSG), named Károly Ebeling, worked tirelessly in support of naming the bridge after Széchenyi. However, he never saw his efforts come to fruition, as he became the first Hungarian victim of World War I, sadly as a civilian.

The Rákosi coat of arms was placed on the bridge in 1949. It was replaced with the Kádár coat of arms in 1973. These were covered in 1992, and in 1996 the original coat of arms was put back in place.

Cover photo: The unique, stunning, unforgettable Chain Bridge (Photo: Both Balázs/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration