PestBuda recently reported that a decision had been made to renew the Pest embankments. But what are these structures, and why are they called embankments?

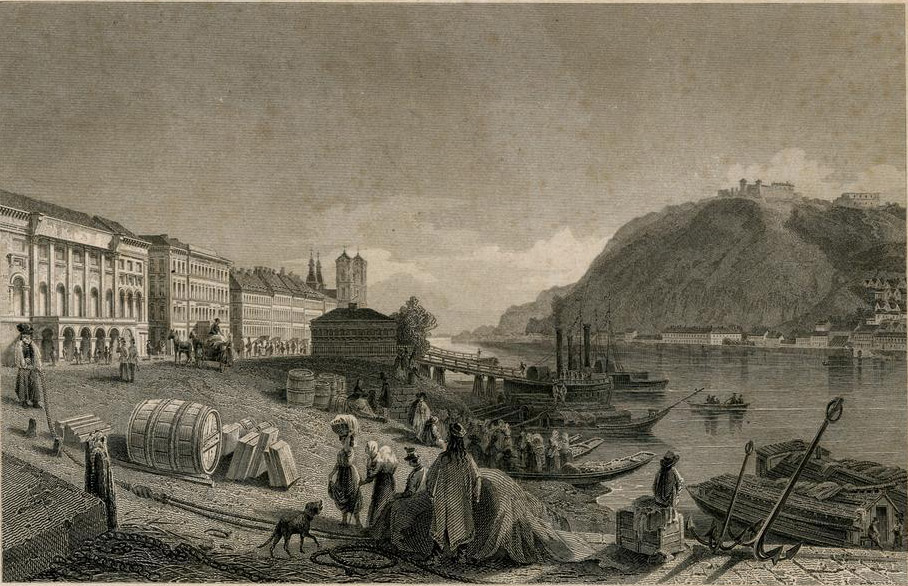

The embankments of Budapest are fantastic creations, and their role is invaluable. Contrary to their Hungarian name (rakpart, i.e. loading quays), their main task is not to ensure the loading of ships but to offer protection from floods, but this was not always the case: the Danube Banks of Buda and Pest were much lower at the beginning of the 19th century. Anyone could walk down to the muddy, undeveloped riverbanks and nothing stood in the way of the flooding Danube.

Engraving of the undeveloped quays by Ludwig Rohbock in the 1850s (Source: FSZEK, Budapest Collection)

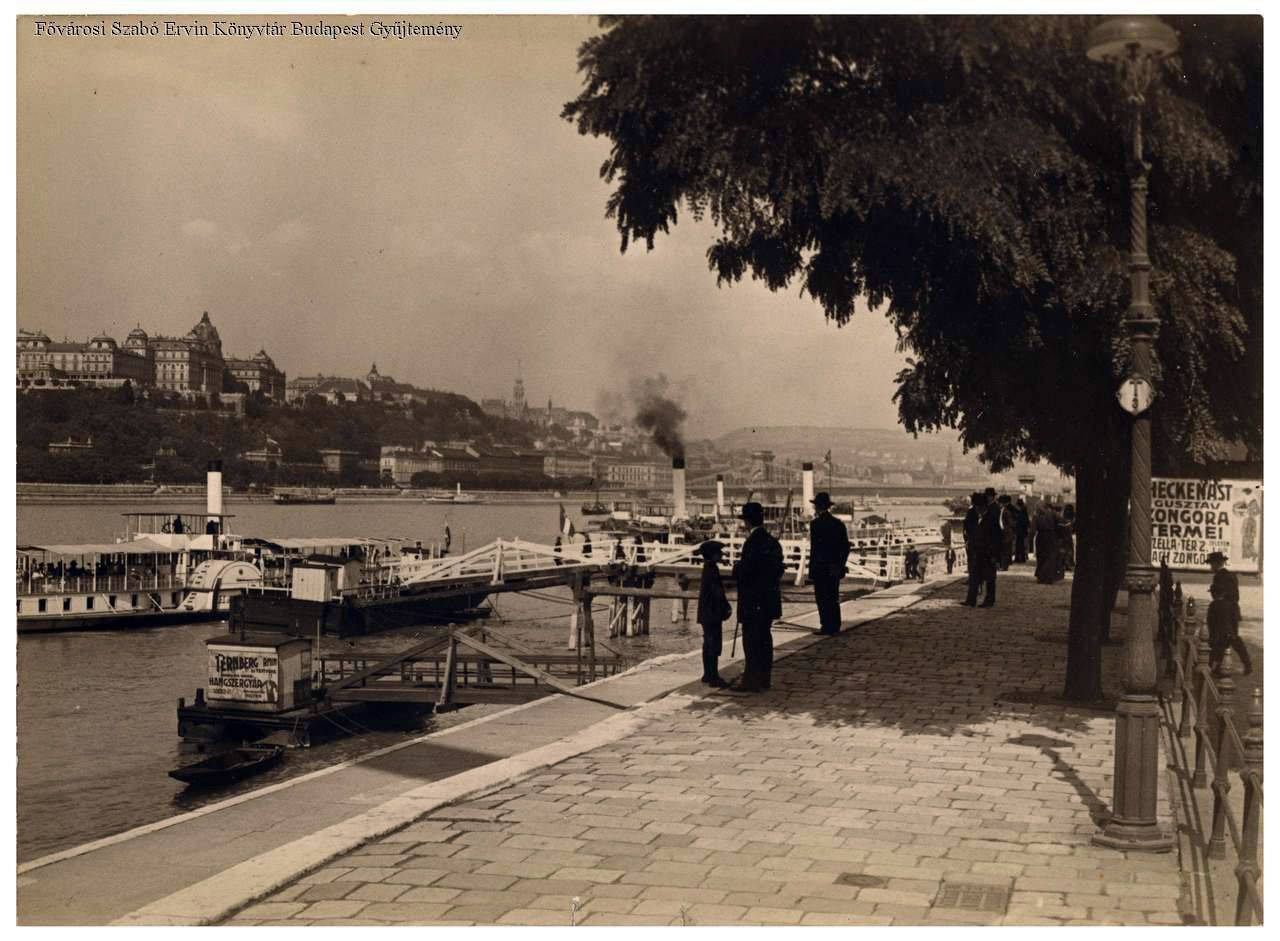

The inauguration of Chain Bridge in 1849 caused the first changes. During the construction of the bridge, steamboat traffic on the Danube was already lively. To ease mooring, the First Danube Steamboat Shipping Company (Dunagőzhajózási Társaság) built a 300–350-metre-long pier on the Pest side between 1853 and 1857.

With this, the background of a much larger construction was prepared: rebuilding the entire Danube Bank. Since the flood of 1838, which ravaged Pest, it had become clear that something needed to be done against the floods. The most obvious was to reduce the factors that caused the floods and, on the other hand, raise the shores.

The Vigadó had already been built, but the embankments had not been completed in the 1860s (Photo: FSZEK, Budapest Collection)

Constructions began in the 1860s. This brought three significant changes in the life of Budapest and the suburbs. On the one hand, the one-kilometre-wide river at Lágymányos was narrowed to 400 metres, eliminating the possibility of an ice dam forming here. On the other hand, the Soroksár Danube branch was closed (Ráckeve).

The third task was to build the embankments of the Danube. From the 1860s onwards, the embankments in Budapest were built continuously with the help of renowned engineers such as Ferenc Reitter.

The height of the embankment was adjusted to the highest level of the flood (which for a long time was in 1838), and the stone ledge ended a metre above it. The embankments have two levels in many places: ships moored to the lower embankment while they moved goods. The upper quays became a popular promenade.

People admiring the panorama of Budapest and the Royal Palace on the promenade of the Danube Bank in Pest in August 1916 (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The embankments played an important role in trade on the Danube. It is no coincidence that an Elevator house, public warehouses, and customs were built next to the Danube in the vicinity of Boráros Square for the loading and storage of grain. Moreover, a freight station operated to the south of the public warehouses until the 1990s.

However, with the opening of the Csepel Freeport, the key commercial function of the quays ceased, and in the 1920s and 1930s, ships were no longer unloaded here. For a few years, the quays were “empty”, meaning there was no significant traffic on them. They could have been parks or promenades.

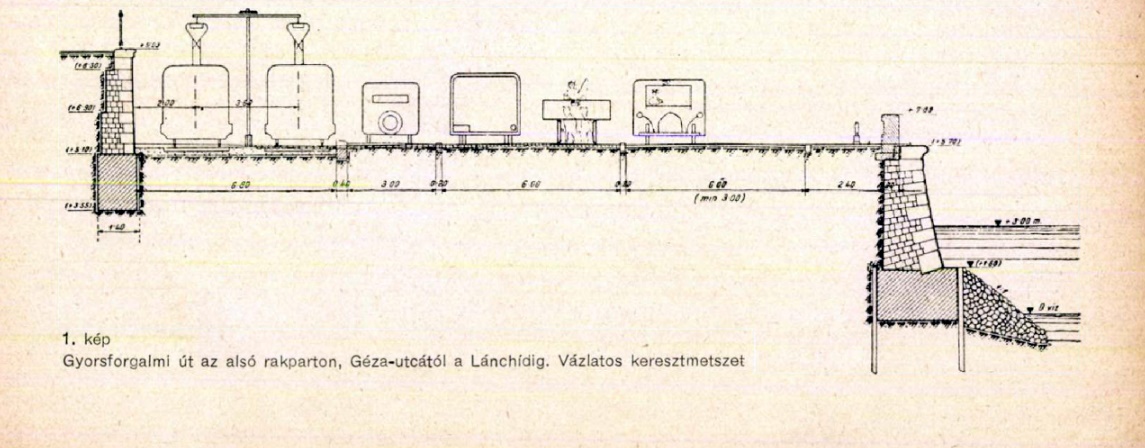

However, urban development took a different direction. At the end of the 1930s, Pál Álgyay Hubert developed a large-scale plan for the Pest embankment. His idea was to build a high-speed tram and a main road specifically for cars. Work began: the road and the tram underpass were built at the bridgehead of the Chain Bridge in 1939, although trams did not run through it yet. Tracks were only laid through the runner when Chain Bridge was rebuilt after the war.

Cross-section of the planned road in the introductory article written by Pál Álgyay Hubert (Búvár, 1 June 1937)

Trams have been running on the embankment for a long time. The line was built on the Buda side before the turn of the century, with the underground bypass of the Buda bridgehead of Chain Bridge. South of the Chain Bridge in Pest, the tram was built between 1897–1900. This section essentially rests on a nearly half-kilometre overpass built on the lower quay because this was the only way to ensure that the popular promenade on the upper embankment did not disappear while the loading of ships on the lower embankment could continue.

For well over 15 years after World War II, the embankments performed the same function as before, serving sparse traffic, but as the use of private cars was severely limited, it did not bring a significant number of cars to the Danube Banks.

From the 1960s, Budapest's transport policy changed, with urban expressways planned through the capital. The embankments of Buda and Pest were included among these expressways, i.e., they became the north-south transport corridors of Budapest. At the same time, increasing traffic completely blocked the people of Budapest from the Danube.

The Bem Embankment as a main road in 1973 (Fortepan / No.: 195104)

The fact that green parks and spaces for pedestrians and residents should be created on the Danube Banks is not a new idea – despite the recent intensification of efforts to transform the embankments. In 1864, Mihály Táncsics sharply criticized the city administration because they sold the areas gained by filling and narrowing the river to build houses instead of creating parks along its length.

The embankments are the longest historical monuments in Budapest. In 2011, they were named a group monument surrounding the Danube Banks for 12-12 kilometres on either bank.

Cover photo: Costers, steamboats and lively trade in the second half of the 19th century. (Photo: Fortepan / Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.07.004)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration