The bridge law, promulgated on 2 May 1836, provided that a public limited company could build a bridge between Pest and Buda, levy customs duties for a specified period, and after that, the bridge would become the property of the state. In addition, the law appointed a committee to clear any questions, such as a contract with the public limited company.

The law is also referred to as an important step towards equality of sacrifice because it stated that:

㤠2. Everyone, without exception, has to pay customs Рonly in this case, and without any consequences drawn from it, only during the contractual period to be concluded by the National Delegation with the public limited company and to be determined below Рon the permanent bridge to be built between Buda and Pest at the expense of the public limited company."

That is, the customs were not a fee for a service. The nobles had had to pay for services before, for example, in inns for accommodation, for meals, for transport in a mail car. With the bridge law, the public limited company was granted the right to collect customs between Pest and Buda.

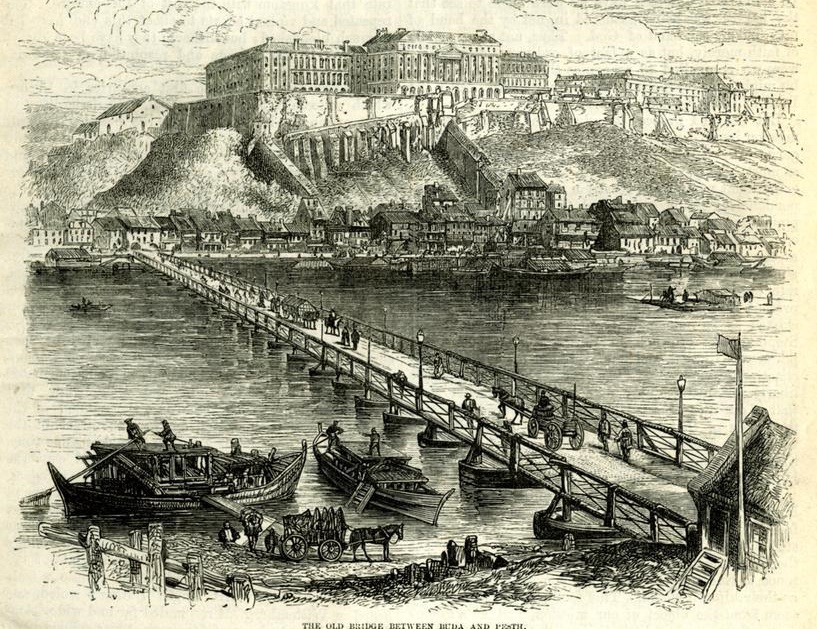

The bridge was owned by the cities, and the collected customs belonged to them, this was difficult to give up (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The cities were therefore compensated by a law passed 185 years ago, which also stated that the nobles were not exempt from this toll, contrary to previous provisions and the centuries-old principle of noble tax exemptions.

From today's point of view, it may be surprising that a right to collect customs, derived from the Middle Ages, was granted to a public limited company, but this was the first law to apply the principle of equality of sacrifice in Hungary.

Another revolutionary novelty of the law is that it stated: a public limited company will build the bridge. Until then, this form of enterprise was not known in Hungary, there was no Hungarian word for it (the original text of the law was Latin). The word public limited company (hun. részvénytársaság') was coined by István Széchenyi.

The most conservative nobility of the country did not even want to hear about a private company building a bridge and everyone having to pay a toll for its use as this went against one of the cornerstones of the traditional constitution. For the Viennese government, the issue of the Pest-Buda bridge was uninteresting: although it was not opposed, no money was sacrificed. Fortunately, the country's palatine, Archduke Joseph, supported the construction of the bridge, and his influence helped a great deal.

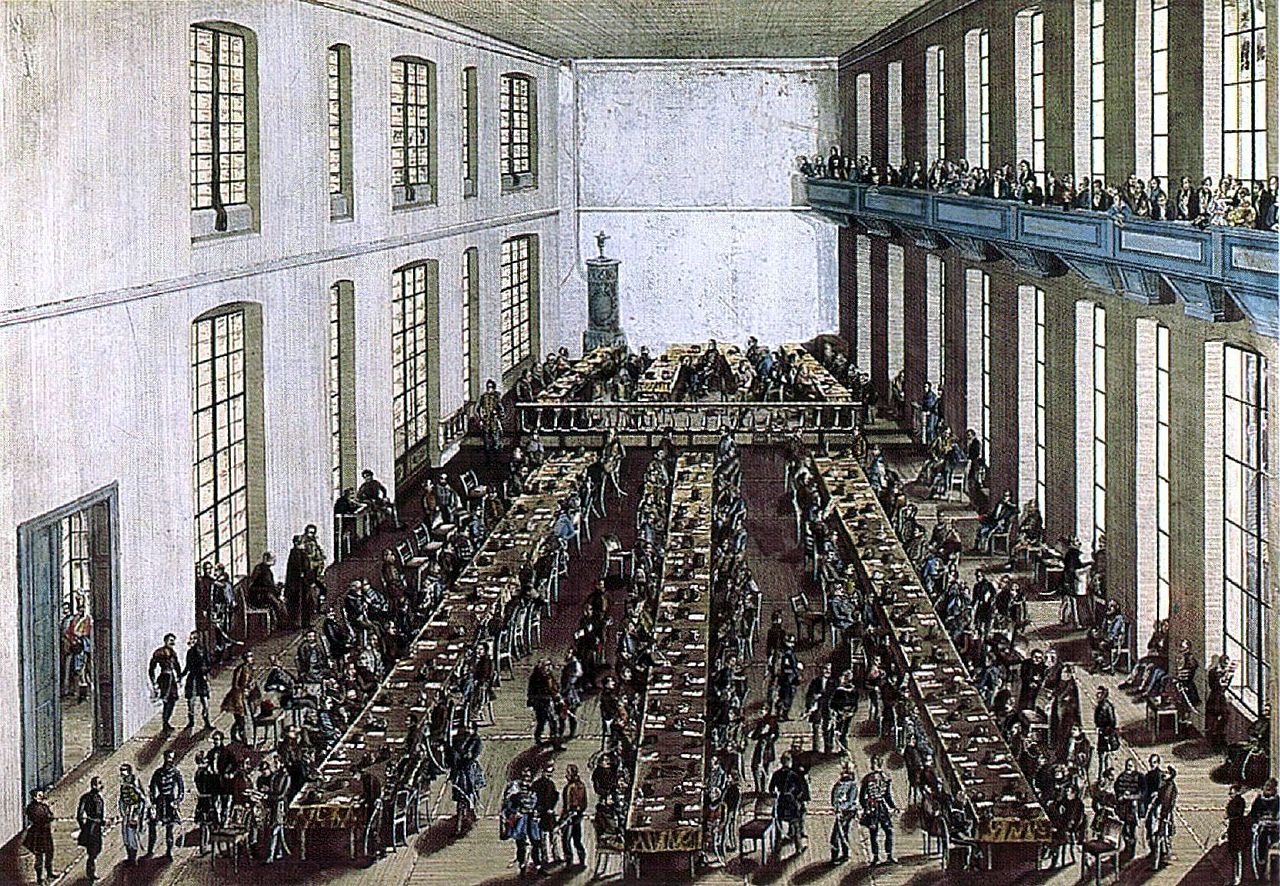

The law allowing the construction of the Chain Bridge was preceded by a long debate (Photo: Balázs Both/PestBuda.hu)

The two cities, Pest and Buda also opposed the construction of the bridge in this form for a long time. On the one hand, there were fears that the pillars to be built into the Danube could cause flooding. In addition to the technical problem, there was also a serious economic-legal conflict between Széchenyi and his circle, who designed the bridge, and between the two cities.

Namely, Buda and Pest collected a great deal of income from the pontoon bridge, the operation of which was leased to a contractor. And now they were asked to give up that revenue, transferring their right to collect customs to a private company for decades. Of course, there was a great debate, several consultations were held between politicians and city leaders.

The issue was urgent, as the adoption of the bridge law was conditional on the two cities renouncing the pontoon bridge and customs. If the city-operated bridge were to remain, the previous rules would remain in force on it, and the new permanent bridge would not provide enough revenue and the company could go bankrupt.

To find a solution, Széchenyi and his circle even committed a minor scam. Gyula Viszota described the fate of the decision made by the Pest Council in his work, “The History of the Széchenyi Bridge”:

“The vote showed that there were 21 votes in favour of the proposal of the Council (decision to relinquish ownership - Ed.) and 48 in favour of Kolb's (a councillor who insisted on property rights - Ed.) proposal. This result was shown to the palatine along with the proposal. And yet, the palatine stated in the House of Lords that the elected citizens also contributed to the wishes of the orders.”

This was possible because the city clerk, János Lechner, formulated the city statement ambiguously, in which each party was able to imply its own version.

Sitting of the Status et Ordines in Pozsony (Pressburg, now Bratislava, Slovakia), in the Parliament of 1832–1836 (A. J. Groitsch copper engraving)

Compensation for the two cities was provided by law but there was no mention of how much to pay. Because of this, the cities and the later Chain Bridge Public Limited Company went to trial and it was not until 1863–1864 that they agreed with each other. According to the agreement, the company will pay (to Pest in 1931, to Buda in 1936) 200–200 thousand forints, but in the meantime, it will pay interest on the amount, twelve thousand forints a year.

This obligation was later taken over by the state, but the interest was paid by the state only until 1885 when Budapest waived this. Budapest and the state only agreed on the amount of compensation payment itself in 1938.

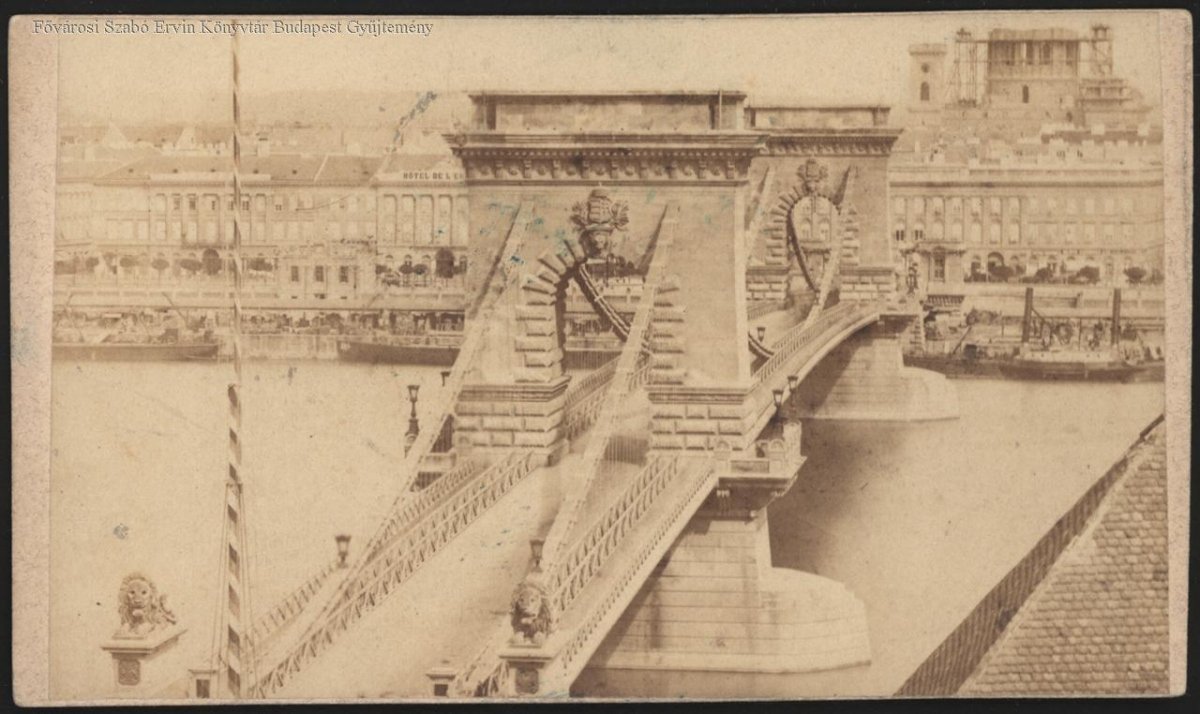

Opening picture: One of the first photos of the Chain Bridge (Source: FSZEK, Budapest Collection)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration