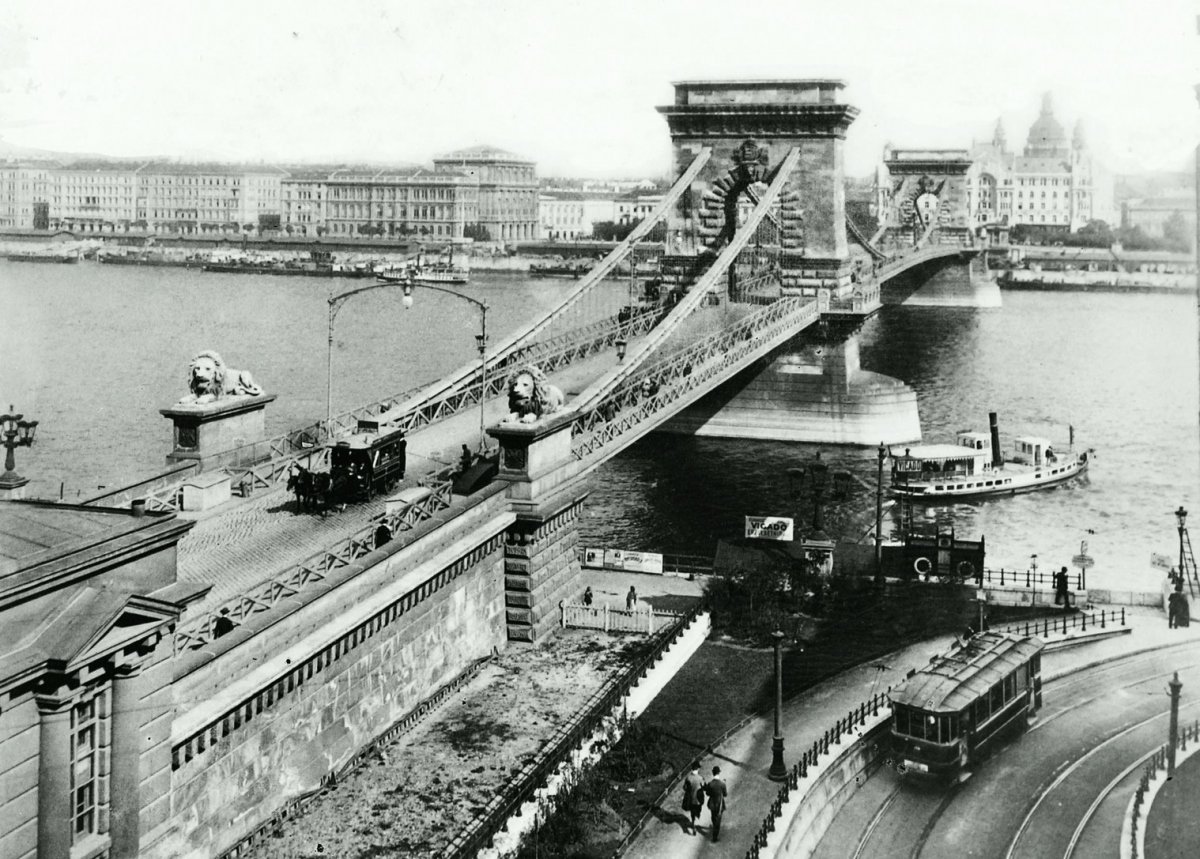

The Buda end of the Chain Bridge was one of the most important transport hubs in Buda already in the 19th century. There was a tram from the bridgehead (which was called Clark Ádám Square from 1912) as early as 1896, but only to the north. There was no tram south of the bridge, and although the Budapest Public Road Rail Tracks Company was keen to build the line, the leaders of Budapest and the Public Works Council had long debated how to do so.

For a long time, trams could only run north of the Chain Bridge. When the picture was taken, in 1908, the continuation was completed (Photo: Fortepan/György Klösz, Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.08.139)

It was not even a problem that the Chain Bridge was in its way, since as early as 1895, when the electrification of the horse-drawn railways was decided, it was known that a tunnel would be needed at the bridge. In the official report of the Budapest Public Works Council in 1899, this can be read about the agreement made with the tram company in 1895:

“If the capital city authority finds it necessary to connect the road railway line at the Chain Bridge with the road railway line planned on the other side of the Chain Bridge to Rudasfürdő with the help of a tunnel, possibly in another appropriate way: the contractor undertakes to establish this connection; provided that its implementation does not present major technical difficulties."

At the Chain Bridge, the surface tracks of the tram could not be solved, as the traffic would have drowned in chaos at the much better built-in bridgehead at that time. The tram, therefore, had to cross the path of the bridge in a tunnel.

The issue was first seriously raised in 1898. The main issue at the time was not the bridge, as they already discussed that, but because the parties could not agree on how and where to run the tram south of the bridge.

The park at the end of the Chain Bridge before the construction of the tramway (Photo: Fortepan/György Klösz, Budapest Archives, Reference No.: EN.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.026)

There was talk of the lower embankment, the upper embankment, but also of taking the line through a tunnel. The Public Works Council protested against the surface, upper embankment trail because they wanted to keep the Upper Embankment completely a promenade. There was no such problem on the lower embankment, it would not have disturbed the promenades or the view, but it was eventually vetoed by the Ministry of Agriculture because if the tram had been run here, it would have weakened the protection against floods. Authorities in the capital then suggested that the line be routed on a viaduct built above the lower embankment. (This would have been a similar solution as tram 2 on the Pest side).

However, none of the options examined were acceptable to everyone, so the question was dropped at that time. In the following years, the parties insisted on their opinions, so the issue was delayed, the capital proposed to set up a committee, but the Public Works Council was not really a partner in this.

However, the tram line was increasingly needed. The General Assembly of the capital decided in April 1900 to support the solution of lowering the tram line in the small parks near the bridgehead, bypassing the bridge and bridgeheads in a tunnel, and then running the tram on the surface of the Várkert Embankment, i.e., the upper embankment. However, this was not acceptable to the Public Works Council for the reasons already mentioned above.

The Public Works Council would not wanted to see a tram here (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 82522)

Then the government intervened. The Minister of Commerce convened an administrative on-site visit on 18 March 1901, where, however, the contradictions could not be clarified. The controversy did not come to a standstill even in November 1903, so the capital again turned to the government, which finally stood by the capital's plans on 19 February 1904, to support the short tunnel around the bridgehead and the tram line on the Várkert Promenade.

After this government decision, things happened faster, the ministry held a licensing hearing on 28 June 1904, where the parties finally agreed, everyone accepted the idea of the capital, and the line received the license, which was published in the 15 July 1904 issue of the Fővárosi Közlöny:

“The Budapest Road Railway Company receives a permit and at the same time undertakes to bypass the bridgehead from the endpoint of the Chain Bridge-Óbuda branch in a tunnel-like underpass, in addition to the appropriate widening of the upper embankment with the help of an external retaining wall to the Fiume Hotel, and from there on the Várkert Embankment and Apród Street, to build a road railway to Szarvas Square and shall operate it continuously during the period of authorization of its core network."

The tunnel was required to be similar to the Millennium underground's tunnel, and even the exact composition of the concrete was determined:

"A concrete mixture of 1 part Portland cement and 7 parts Danube gravel shall be used for the sidewalls and bottom masonry and 1 part Portland cement and 6 parts Danube gravel for the vaults between the iron girders."

They also stipulated that the visible structures should adapt to the style of the bridge, that they should be agreed with the Budapest State Bridge Inspectorate, and, of course, that the parks that had been disturbed by the construction should also be restored.

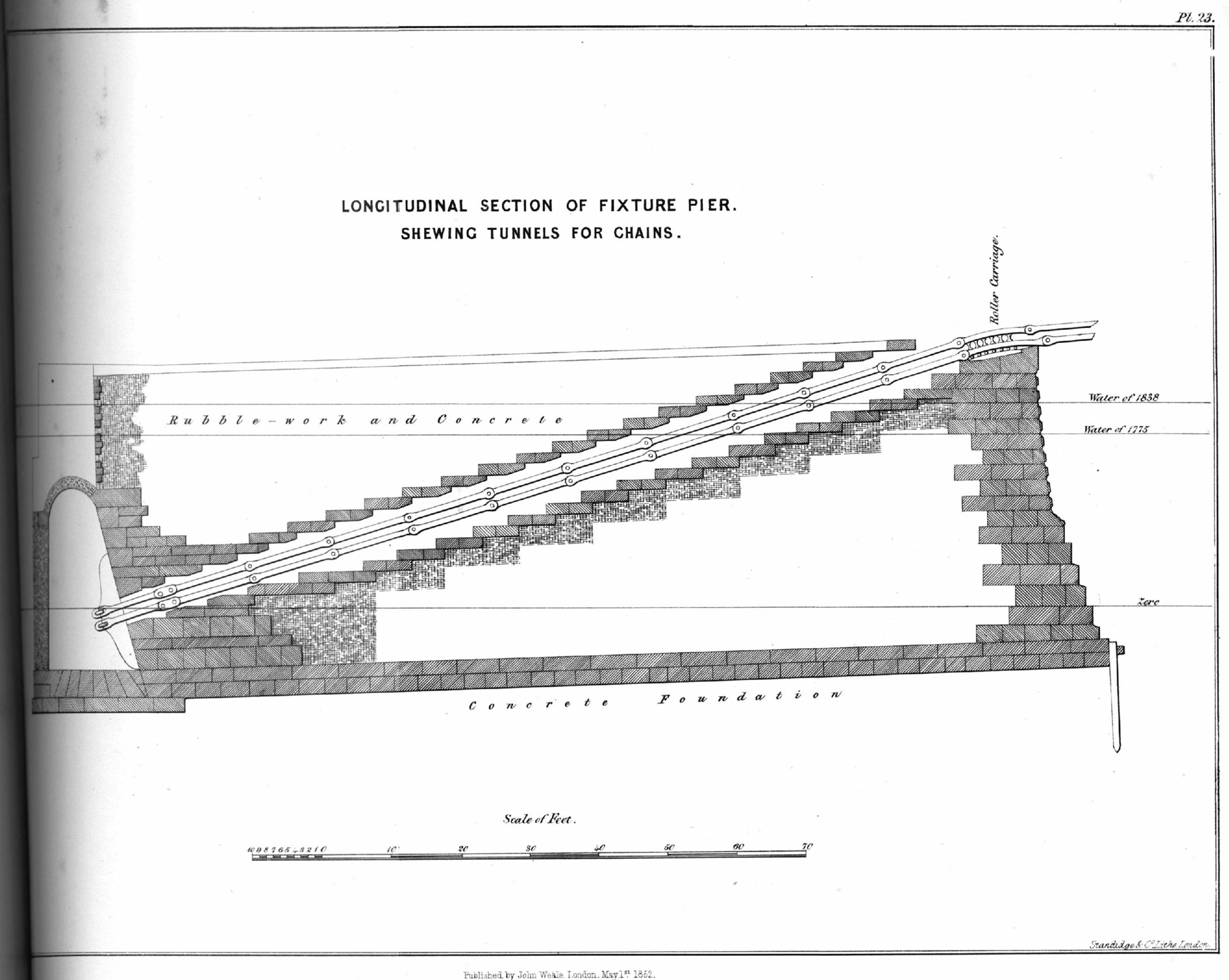

The massive bridgehead of the bridge could not be drilled. The drawing published in W. T. Clark's book in 1852 shows that under the ground the chains run into the anchor chamber.

Work could then begin, not only on the construction of the surface tram line but also on the short, 44-metre tunnel bypassing the bridgehead of the Chain Bridge. The massive bridgehead could not be drilled straight through because of the chains and chain chambers running inside it, they had to be avoided, so the tunnel became curved. In the newly completed tunnel and on the Várkert Embankment, trams were finally allowed to start 115 years ago, on 31 January 1907.

Cover photo: Tram at the new tunnel in 1908 (Photo: Fortepan/Hungarian Geographical Museum, the company of Mór Erdélyi)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration