On 29 August 1541, the Turkish army occupied Buda with a trick, and the period of about 150 years of occupation began. As it was a military occupation of the city, buildings and fortifications were built mainly for military purposes, but there are also a good number of mosques and baths.

"In Buda, the Turks built nothing apart from mosques, one of which was in today's Viziváros and one in Ráczváros, and baths."

- wrote Ferenc Salamon in his historical work entitled Magyarország a török hódoltság korában [Hungary in the Age of Turkish Occupation], published in 1864.

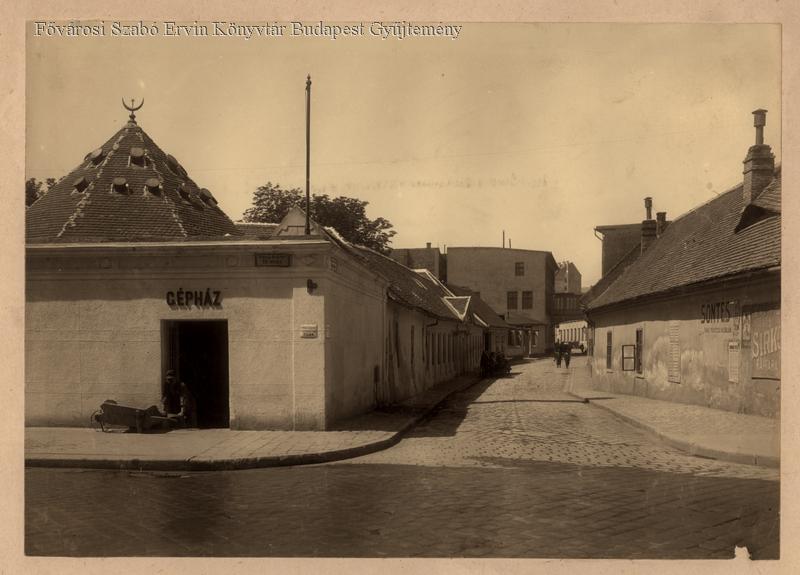

The bath at the corner of Fő Street and Ganz Street in the 1900s (source: FSZEK, Budapest collection)

During the quieter periods, many Turkish and Western travellers came to the city, and the time they spent here is remembered in their travelogues. Among the buildings in the capital, they wrote mainly about the Buda baths, as they played an important role in the daily life of the Turks. Nevertheless, little mention is made of the Király Bath, although it is a very special building.

In the Middle Ages, there was no building with a similar function on the site of the Király Bath as in the case of today's Gellért, Rácz or Császár Baths. The simple reason for this was that this area of the Viziváros did not have a direct water base. For this reason, the Turks were forced to build their baths outside the city walls, around the spring group of Gellért and József hills. However, this raised the question of how they would clean themselves during a siege when the city was completely surrounded. For this reason, it was decided to build a bath within the city wall, today’s Király Bath.

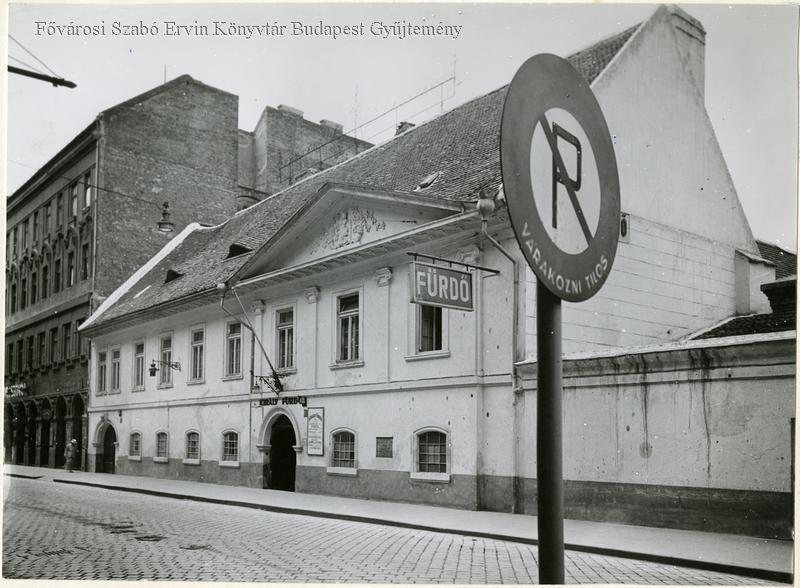

The Király Bath in 1958 (source: Fortepan / No. 02898)

The bath was built near one of the busiest gates, the Kakas Gate (which may have stood around today's Bem Square), so it was named the Kakas Gate Bath at the time. Its construction was probably started by Pasha Arslan in 1565, who was executed a year later by order of the sultan, so the work was completed by the next pasha, Szokoli Mustafa. By then, all that was left was the vaulting and furnishing of the rooms.

In terms of its floor plan, it can be said to be the basic type of thermal baths in Hungary. The three halls - the foyer, the transition room and the pool hall - are located in one axis. All that remains today is the central pool hall and the three smaller rooms attached to it, which could probably be used for undressing, relaxing, and depilation. The bath received its thermal water from springs around Lukács and Császár baths, which the Turks led into the city wall with the help of underground pipes.

“The ilidice of the Choros Gate: inside the gate is a small and useful bath. It is built over eight arches and has a pink dome covered with ceramic. All the way to the four sides of the pool in the middle, clear warm water flows from the mouths of lions day and night. However, it is very hot so that one cannot go in "

- Evlia Cselebi, a Turkish traveller, remembers it when he visited Hungary between 1664 and 1666.

Facade of the spa facing Fő Street from the 1930s (source: FSZEK, Budapest collection)

On 2 September 1686, the imperial armies succeeded in recapturing the city. The bath luckily survived the siege and the ensuing three-day sacking. As a building without owner, it became the property of Emperor Leopold I, who, together with the Rudas Bath, donated it to his court physician, Frederick Illmer of Wartenberg, in 1687. After his death, it was inherited by his son, Károly Illmer, who did not bother much with his inheritance, and sold it to the castle commander of Buda, János Pfeffershoven, for 5,000 gold forints. The purchase price was quite high, so we can assume that the bath was working well at the time.

The first major expansion of the building is probably due to Aigner Leonhard, a bath owner and surgeon who bought the building in 1718. The baroque part of the building can be connected to his name, ie the facade facing Fő Street, which was built on the site of the Turkish-era lobby. Little is known about the construction, as the later classicist reconstruction almost completely removed its traces.

Restoration of the bath in the 1950s (source: Építés- és Közlekedéstudományi Közlemények, 1957)

The condition of the yard during the restoration (Source: Építés- és Közlekedéstudományi Közlemények, 1957)

After the Baroque enlargement, the bath was not dealt with too much. This is mainly due to the decline of the bathing culture of the 19th century. The institutions were no longer visited as much at that time, and as they were not profitable, they did not pay much attention to their maintenance and expansion.

The bath, which was no longer in very good condition, became the property of the König family in the end of the 18th century, to whom it owes not only the classicist reconstruction and parts of the building, but also the name given to it today: the population soon began to call it Königsbad, or Király [King] Bath.

Statue of Sándor Szadai entitled Női akt tállal [Women's Nude with Bowl] in 1967 (source: Fortepan / No. 252361)

Ferenc König bought the building in 1796 for 13,000 forints, but he no longer had enough money to renovate it. The not-so-inspiring sight of the bath was also noted by Austrian painter and lithographer Franz Schams in his 1822 German-language work on Buda. After the death of Ferenc König, another member of the family, Mihály König, bought the building from his widow, who was not only the owner of the Király Bath, but also the tenant of the Lukács and Császár Baths. He had the financial background to entrust the Viennese architect Mathias Schmidt with the reconstruction and expansion. The exact time of the works is unknown, but they may have taken place between 1827 and 1837. It was then that the Baroque wing was remodelled and expanded with an additional classicist building section.

In the second half of the 19th century the bath had a good reputation, a special omnibus was launched from Pest to the Buda Baths, one of the stops of which was the Király Bath. In the 1870s, a public kitchen was also operated in the building.

The pool hall of the Király Bath (source: Budapest Gyógyfürdői és Hévizei Zrt.)

One of the pools of the Király Bath (source: Budapest Gyógyfürdői és Hévizei Zrt.)

The inner courtyard of the bath with the outdoor tub (source: Budapest Gyógyfürdői és Hévizei Zrt.)

“A boiler explosion took place yesterday night in the Király Bath in Buda. A 72-year-old machine operator was tasked with guarding the machine. But the old man fell asleep next to the machine, and during this time the rapidly developing steam blew up the top of the boiler. Steam erupted at the main valve and the explosion was so great that part of the building's roof fell onto the courtyard and another onto Fő Street. The old operator suffered several injuries to his head and arms, but miraculously he had no major injuries. ”

- writes the Fővárosi Lapok on 23 June 1888. An official who arrived because of the sad incident found that the boiler in the bath had not been inspected for five years.

World War II caused more damage than the boiler explosion. Although the classicist parts of the building were damaged, the Turkish pool hall miraculously suffered only minor damage. Prior to the restoration work, excavations were carried out in the bath area, during which more valuable finds were discovered: in the courtyard of the bath, for example, they managed to find a completely intact section of the Roman war road next to many Turkish rubble. The work was started in 1955 according to the plans of architect Egon Pfannl, with the aim of strictly preserving historical fidelity, but also having to take into account modern health and balneological aspects.

Participants in the most recent 2017 call for ideas had to meet similar criteria. The winning architectural firm designed contemporary additions to the existing historic parts of the building and developed two main functional units. One is the Turkish zone formed in the Turkish-Baroque historical units. The other is the wellness zone in the new wing of the building, which would be complemented by a sauna complex. They also consider it important to emphasize the original Turkish domes as much as possible.

One of the visual designs for the 2017 winning entry. In the background are the Turkish domes (source: 3h Építésziroda).

Visual design of the pool hall (source: 3h Építésziroda)

Visual design of the spa (source: 3h Építésziroda)

There will also be a rooftop jacuzzi pool with a good view of the bath and the Classicist, Baroque and Turkish parts of the building - making the whole complex visible from here. The bath is protected as a monument, therefore the design office constantly consults with the client, the monument protection authority and other specialized authorities.

Cover photo: Király Bath (source: Fortepan / No. 120708)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration