The history of Pesterzsébet dates back to the 1860s, when the area of the Gubacs Prairie belonging to Soroksár was started to be parcelled out. Two settlements were created: one was named Erzsébetfalva after the Queen and the other was Kossuthfalva. In 1897, under the name of the former, they merged and separated from Soroksár, becoming an independent large village. The population grew at a rapid pace, so in 1923 it was given the rank of a town with an orderly council, thanks to which its name was changed to Pesterzsébet the following year. On 1 January 1950, it became part of Budapest as the 20th District of the capital.

Erzsébetfalva on the Third Military Survey Map of the Habsburg Empire between 1869 and 1887 (Source: hungaricana.hu)

The rapid population growth of the turn of the century soon justified the establishment of a larger elementary school, and in 1916 the Ministry of Religion and Public Education commissioned Jenő Lechner to draw up the plans. The fact that he was Ödön Lechner's nephew did not play a role in the election, as he already had nice references in the field of educational buildings. In 1909 he planned an elementary school for Kóspallag in Börzsöny, in the same year he won the tender for the State Teacher Training College in Sárospatak, and the following year he was able to build an elementary school in Hernád Street, the 7th District of the capital. In 1911, a high school boarding school was built in Munkács, and then a civic girls' school in Aranyosmarót, in the highlands, according to his plans.

The elementary school on Hernád Street was also designed by Jenő Lechner (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

His uncle also had an extraordinary influence on him, but he saw that conservative society was reluctant to accept Hungarian Art Nouveau buildings, especially the facades associated with followers of Ödön Lechner. Therefore, Jenő Lechner wanted to create a national architectural style by reviving an existing historical style that seems valuable to the average person. In the course of his research, in which he relied significantly on the results of art historian Kornél Divald, he found that the renaissance style moulding of the 16-17th century has the Hungarian spirit, which can be further developed as the basis of a national architectural language.

The State Teacher Training College in Sárospatak was built between 1909 and 1912 (Source: Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre)

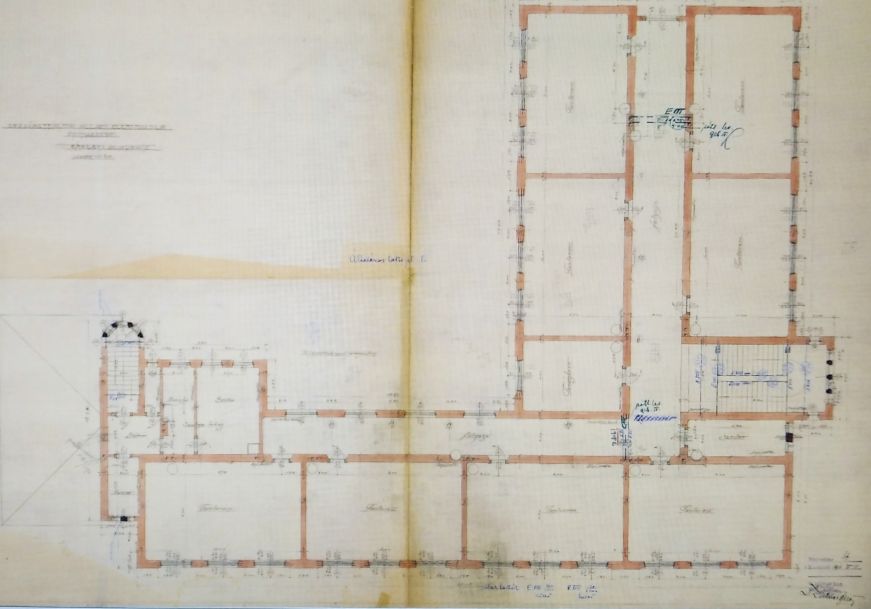

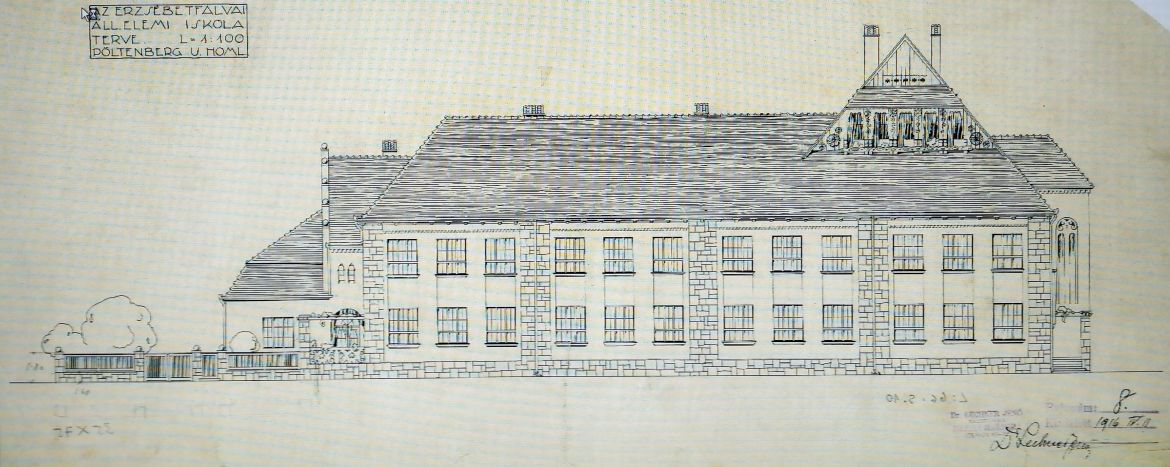

He was able to implement this in practice and on a large scale for the first time at the State Teacher Training College in Sárospatak, which he designed together with László Warga and was built in 1912. He was already working on the school in Pesterzsébet, armed with the experience gained there. He edited an L-floor plan, single-storey building, the longer part of which runs along Pöltenberg Street, however, the shorter wing of Lázár Street can be considered the main tract, as it is wider and the main entrance opens here as well. There are four classrooms in each part of the building, but while in the longer, these are lined up next to each other, in the shorter they open to the left and right of a central corridor. The same layout applies upstairs, to where a staircase leads up from the foyer behind the main entrance.

Floor plan of the school in Pesterzsébet (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

Despite the relatively small size of the school, it has a rather busy mass system: a narrow protrusion (called risalit) pops out strongly from the main tract. Adjacent to the end of the long wing is a semicircular staircase from the courtyard, and as a continuation of the wing, the originally ground floor house of the 'pedellus' (school assistant), which has since been extended to a storey, is attached. The transition between the school and the house of the pedellus is provided by a short connecting wing. Lechner also increased the agility by making the main wing asymmetrical: he placed the risalit in the left third of it, and the main entrance opens even more to the left.

The main facade of the school faces Lázár Street (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Lechner's idea of a new style can be seen mainly on the roof and in the upper part of the facade. He also made two versions of the plan: on one of them, the ridge of the gable roof runs very high, and he closed the upper part of the gables with so-called sawn planks, which are often used in folk art. This actually means that the surface of the wood was broken through with smaller openings that usually gave the shape of hearts, birds or flowers. The lower part of the high gable is located under a drain, and the edges of the attic windows opening here would have been carefully carved by the designer, the dividers between them, and the lower corners of the gable would have been decorated with plant patterns. It can be read from this plan of Lechner that he was also touched by the national romance represented by Károly Kós and his friends, who tried to give Hungarian architecture a domestic character by reusing the forms and structures of folk art.

Unrealised design version of the facade (Source: Kiscelli Museum of the Budapest History Museum)

Eventually, however, the other version of the plan was realised, in which the style features of the renaissance style mouldings are dominant. The roof here is much lower, and the end gables have also been left behind, instead, both ends of the ridge are crowned by a moulded pediment. A similarly designed roof extends from the main facade tract, and the short tract connecting the end of the longer wing with the house of the pedellus also received a moulded gable. The latter place would have had a moulding according to the first version, which ended in spheres.

End of the Pöltenberg Street wing before the reconstruction (Source: lazarsuli.hu)

The school, on the other hand, had a rather stylized moulding: while the 16-17th century renaissance buildings consist of elements with multiple articulated profiles, here only simple half-cut swallow-tailed (and a few uncut swallow-tailed) mouldings can be seen. Their foreshadowing was probably the moulding of the tower of the parish church in Késmárk, which was known by Jenő Lechner, as he also toured the Highlands during his research. Not only are the mouldings on the church tower similar, but even their cascading arrangement is a common feature. Incidentally, Lechner used this motif above the main entrance of the Teacher Training College in Sárospatak, but it also appeared in several plans in the later stages of his career.

Cascading moulding crowning the tower of the parish church in Késmárk (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Jenő Lechner's stated intention was to further develop the renaissance style mouldings, so he used top arches in his early buildings, which are not part of the original highland buildings. With this, he did not primarily want to recall the Gothic openings, but rather to follow the arch of the mouldings. Above the narrow and tall windows of the risalit on the main facade, he has engraved twisting loops into the plaster, which he also composed into a pointed arch. With its shape and arrangement, it might have wanted to display an ancient Hungarian tree of life, the trunk of which would be the windows and the foliage of which would be engraved plaster. It is also worth mentioning the pierced, wavy artificial stone railing in front of the main entrance, which is also the same element as the building in Sárospatak.

The risalit has pointed arched windows, above them is the engraved plaster (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

However, it is impossible to leave without mentioning the rectangular windows, which are bordered only by a small ledge, except that, they are completely frameless and ornate-less. In the 1910s, these puritanical openings, which are considered to be forerunners of modernism, began to become fashionable. The simple facades, coated with white plaster, also point in this direction, although the plinths and the rough-walled stone pillars are an important part of the building and give the building a little colour.

Rectangular windows on the side facade (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Thus, there are no significant ornaments on the facade, but on the left side of the shorter wing, a demanding inscription made with sgraffito technique proclaimed the function of the building. As the Hungarian coat of arms was also on it, the inscription disappeared after the Second World War. Incidentally, teaching began in 1917 at the school, which, despite the storms of history, has operated steadfastly to this day. Thanks to its special appearance, the years spent here are perhaps even more ingrained in the memory of young people.

Cover photo: Lázár Vilmos Elementary School nowadays (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration