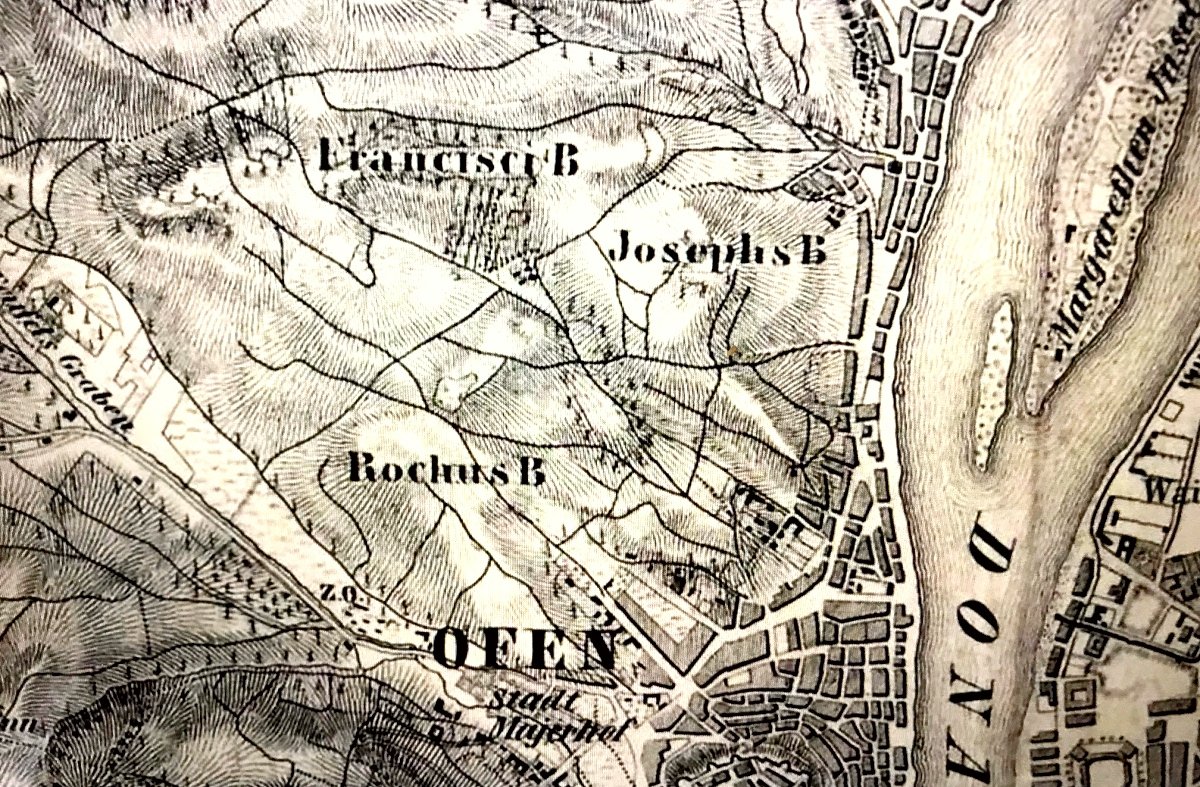

The names listed in the introduction, Burgerberg, Feldhut, Reiche Reid, Dreihotter, refer to the areas and districts of Buda, namely Sasad, Őrmező, Gazdagrét and Csillebérc. After the expulsion of the Turks, Buda was populated by German-speaking settlers at the instigation of the Habsburg ruler (Hungarian settlers were not really welcomed here), they also had political power, and the city documents were mostly in German, so the surrounding mountains and meadows , hills also got German names. As the maps were mostly made for military purposes, the place names were also listed in German, so almost every hill, valley and field had a German name.

However, during the reform era, the German-speaking population of Buda and Pest began to profess to be Hungarian more and more, and the Hungarian-speaking population began to grow.

Tündérhegy in 1909 (Photo: Fortepan / No.: 115816)

Writer Gábor Döbrentei started a movement in 1844 to rename the ridges around Buda. The royal councillor, who was already a great author at the time, suggested in his articles that almost sixty place names in Buda should become Hungarian, and even suggested Hungarian names.

He acted in three ways with regard to naming. The simplest solution was to simply translate the German name into Hungarian, making it Reiche Reid Gazdagrét or Sonnenberg Naphegy. There were areas where he managed to find a pre-Turkish name, such as Kelenföld and Sasad. Where mirror translation or history did not give a “proper” name, a completely new one was invented, such as the name Tündérhegy (which was called Am Himmel in German) or Vérhalom (originally Franzisciberg).

The initiative was successful in three years, and on 11 June 1847, the Buda Council decided on new names. However, if only the city council had decided, it would probably have taken years or decades to naturalize the names of the areas, especially in light of the fact that German became the language of administration again for years after 1849. However, Gábor Döbrentei and his friends were already aware of the importance of proper PR even if they were not even talking about it as such at the time, so they made sure that the new names were part of the public discourse at once.

Sasad in 1986. Its name was Burgerberg in German (Photo: Fortepan / No.: 124554)

After the decision, a larger-scale ceremony was organized on 19 June 1847, to introduce the new place names. On this day, Gábor Döbrentei marched into the Buda hills, leading an upscale company, and the whole Buda hills were baptised publicly and theatrically there. On 22 June 1847, the Honderü - in which Döbrentei fought for the renaming in his series of articles entitled Visszamagyarosítás Pesten [Re-Hungarianisation in Pest] - wrote about it as follows:

“ The solemn baptism of the Buda hills was held last Saturday in the presence of a bright wreath of guests. In this part, on the one hand, we cannot forget to give our warmest thanks to Mr. Gábor Döbrentei for his devout struggles, who for these hills partly researched their old names and partly made up new names for them based on history, and who re-Hungarianised the whole of Buda hills; on the other hand, to thank the noble and Hungarian-minded authority of Buda, which, as appropriate, was not too late in perpetuating this re-Hungarianisation by accepting the sole and exclusive use of these names in the diplomas and other documents to be issued from now on. '

The company therefore marched out, about 150, to Vadászmajor. The program started with the opening of László Hunyadi, then they walked up to the now renamed Tündérhegy, and the resolution was read there. The company then attended a gala dinner in Vadászmajor, effectively ending the great baptism.

Gábor Döbrentei (1785–1851), godfather of the place names of Buda

The cost of the ceremony was raised from public donations, and so much money was raised that some remained, which was offered to the National Museum.

Most of the names have moved into the public discourse, the public consciousness, incredibly quickly. Toponyms that sounded "ancient" appeared on the map - in fact, following former names - such as Kelenföld, Sasad, Nyék. There are popular excursion places among the renamed areas, such as Csillebérc or densely populated parts of the city, such as the already mentioned Kelenföld or Gazdagrét.

Among the 56 names proposed by Döbrentei - and approved by the general assembly of the city of Buda - there were some that did not become established in the end. The area called Árpád orma in the decree (due to the supposed nearby tomb of Prince Árpád, originally Gaissberg) is today called Hármashatárhegy (due to the common triple border of Buda, Óbuda and Pesthidegkút). The Bátoryhegy (originally Lindenberg) has not become established either, today the area is called Hárshegy. But we don't use the names Előmál, Hajnalos, Vajdabérc or Virradó either.

However, Gábor Döbrentei's ridge baptism was extremely successful. As the linguist Géza Balázs explained in his 2006 publication entitled A budai dűlőkeresztelő [The Ridge Baptism of Buda]: "The success can be seen in the fact that it encouraged other city leaders and defenders to create traditional, traditional and new Hungarian names." According to him, the toponymy of Budapest is a faithful reflection of the city's cultural history, and this is due to the local historians who dealt with this issue in the wake of Döbrentei.

The inhabitants of Farkasrét, Gazdagrét, Kelenföld, Kurucles, Kútvölgy, Madárhegy, Mártonhegy, Naphegy, Németvölgy, Orbánhegy, Őrmező, Sasad, Sashegy, Svábhegy, Szemlőhegy, Szépvölgy or Zugliget can definitely thank Gábor Döbrentei and the ridge baptism 175 years ago for the nice names of their neighbourhood.

Cover photo: Őrmező in 1975. Its name was Feldhut in German (Photo: Fortepan, Uvaterv)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration