The Danube section between Pest and Buda is special. The water is deep, the flow regime is variable. Before its regulation, the Danube regularly froze over, and even if it does not freeze completely today, ice still occurs sometimes. For this reason, it was very difficult to build a bridge at this place, even though the crossing here has always been very important from the point of view of traffic. The roads coming from the west - either towards Northern Hungary or the Balkans - crossed the Danube here, and the roads continued from here. There was therefore a pontoon bridge between Pest and Buda already in the Turkish era, then after the expulsion of the Turks, first a reaction ferry, and then a pontoon bridge again from 1767.

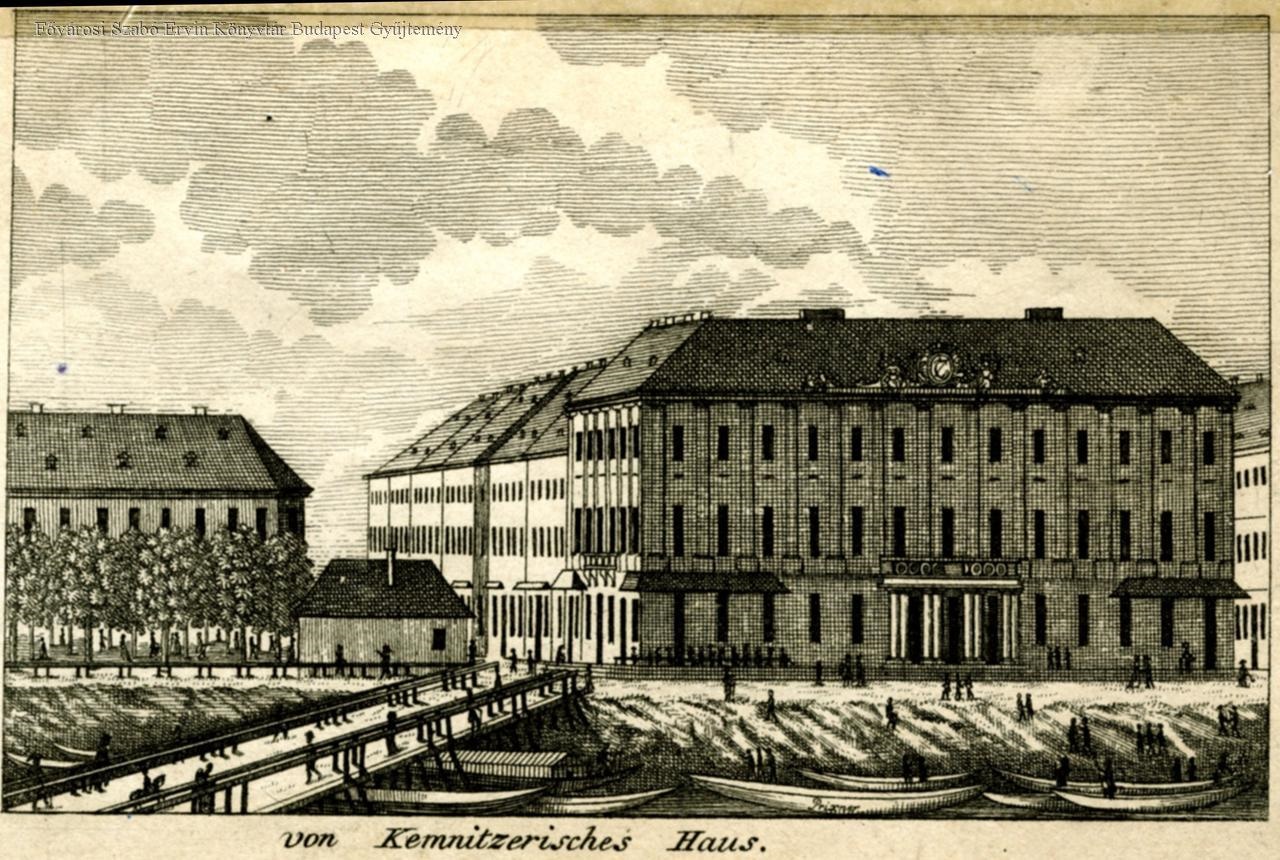

Pest bridgehead of the pontoon bridge (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The pontoon bridge had one huge advantage that later permanent bridges did not have, namely that it could be built virtually anywhere. Why was this important? Because adapting to the needs of the city it could be taken to other locations. When it was erected in 1767, the bridge stood on the line of today's Türr István Street in Pest, close to the northern border of the city. In Buda, the bridge's head in Buda was roughly at the Várkert Bazaar. The pontoon bridge here was easily accessible for the towns, but it was also in an ideal location for passing traffic.

However, twenty years later, Pest decided on a large-scale development, the area between the newly constructed Újépület [New Building] and the then-demolished city walls was arranged according to plan, parcelled out, and a new part of the city was planned here, which in 1790, at the coronation of Leopold II [Lipót in Hungarian], was named Lipótváros in honour of the king. Since the pontoon bridge was no longer suitable in its old location, and they wanted to establish a new market square in the new part of the city, it was decided in 1787 to place the bridge a little further north. Therefore, parallel to the development of the new part of the city, the pontoon bridge was erected further north, in the line of Nagyhíd Street, i.e. today's Deák Ferenc Street. Although the distance between the old and the new place was not great, the bridge in its new place contributed significantly to the rapid development of Lipótváros, for it to become an integral part of the city, and to the establishment of industrial plants to the north of it.

There was a statue of St. John of Nepomuk on the pontoon bridge, which was moved to 2 Eötvös Square after the bridge was demolished (Photo: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

In the new location, the bridge was curved, standing on 45-47 ships. The Hungarian name of the pontoon bridge [hajóhíd] shows that the bridge floated on ships [hajó], and its length changed depending on the water level, i.e. when the water level was higher, the bridge was extended by adding new ships and a track structure built on it.

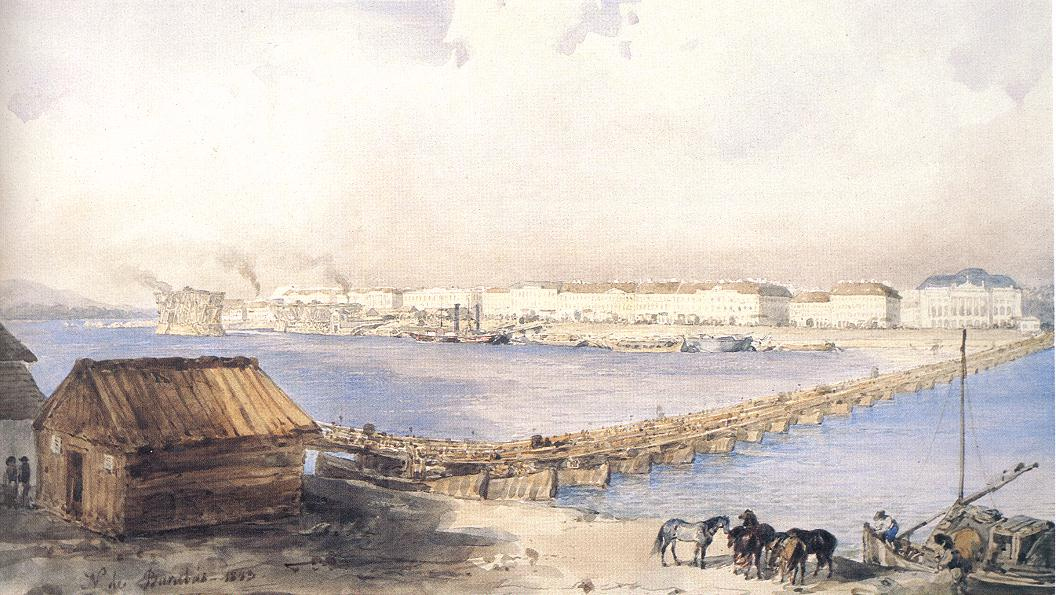

Since the bridge actually floated on top of the water, ships could only pass if the bridge was partially dismantled, i.e. then some parts of the bridge, those closer to the shore, were opened, these pieces were originally created this way. The bridge was usually opened once a day, so it was usually usable for most of the day. However, the bridge was taken out every winter, as the ongoing ice would have destroyed the structure of the bridge, and only put back in the spring, after the ice had retreated. Between the two dates, if the authorities allowed it, it was possible to cross with boats, and if the river was completely frozen over (which did not happen every year, even in the second half of the 18th century), it was possible to cross on the ice. This was strictly regulated by the authorities for the safety of road users.

The pontoon bridge was therefore not permanent, and this was reflected in its shape in the 1820s - we don't know exactly when, but between 1821 and 1827 - it was straightened, at which time only 43 ships were holding the structure.

The owners of the pontoon bridge were the two cities, Pest and Buda, but it was not operated by the city, it was rented out. The bridge was actually a good deal, even though that many people were exempted from paying the bridge toll since you had to pay on the bridge, not actually for its use, but to pay the toll after crossing the Danube, which belonged to the cities of Pest and Buda.

The pontoon bridge on the engraving by Miklós Barabás in 1843

The bridge performed its task perfectly, it was actually enough to serve the traffic between the two cities, although in the middle of the 18th century, the government was already thinking about a second pontoon bridge. However, the cities were vehemently opposed to this, as they did not have the money for a new bridge, but they did not want to see another player in this business. In the debate over the second pontoon bridge, the cities calculated how much a new pontoon bridge would cost, according to the calculations, it would cost 17,000 forints to set up and 1,500 forints to maintain annually. The cities then, at the end of the 18th century, received 16,150 forints from the lessee for the existing bridge, so a new bridge would have consumed the annual income of the old structure, which the two cities could not manage.

The second pontoon bridge was therefore not built, at that time the possibility of a permanent bridge was actually already preoccupying the specialists, even though that in 1810 the competent architectural authority of the Governor's Council stated - actually in accordance with the reality - that a permanent bridge between Pest and Buda, according to the technical standards of the time could not be built. Technical progress (not here, but worldwide) only reached the level at the end of the 1830s that a permanent bridge could be built here.

Cover photo: The pontoon bridge (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration