The history of the Jews in Buda spans around 800 years, and although few sources have survived, the most important chapters are now known, and traces of the former communities are preserved in numerous locations in the Buda Castle. The stories behind them can best be learned on a thematic walk, visiting the locations where generations of Buda Jews lived and were decisive in the life of the community. The Castle Headquarters offers this opportunity with its program titled Shalom, Buda! - Walk in the civic city in the footsteps of Buda's Jews, on which we were guided by Borbála Czakó.

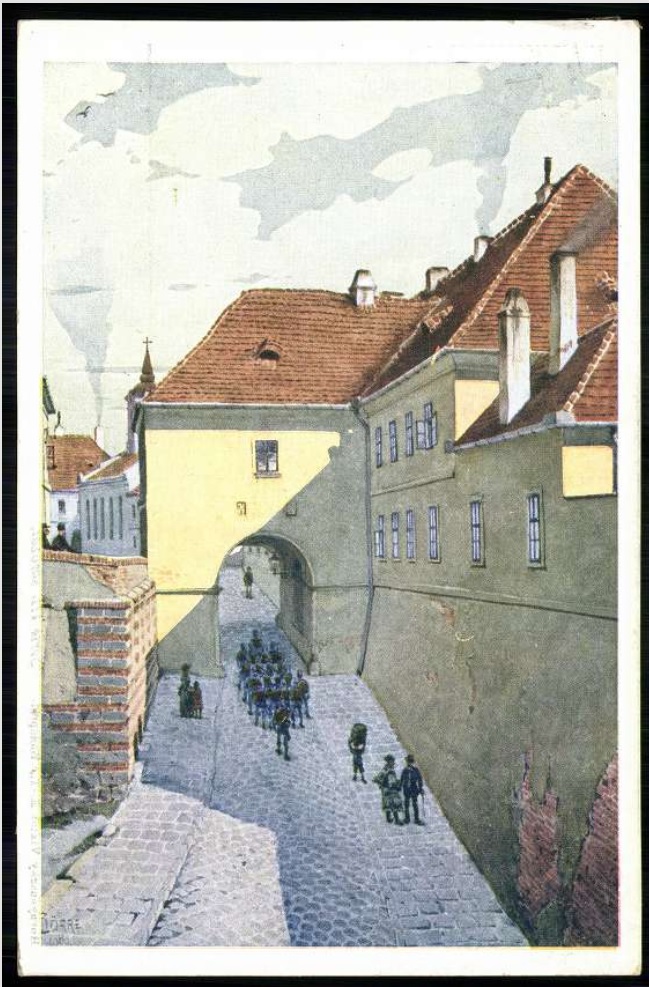

The former Fehérvár gate of the Castle in 1887. The first synagogue in Buda originally stood on the site of the house to the right (Source: contemporary postcard)

The first stop of the story and also of our walk is the area next to the former Fehérvár gate, where Archduke Joseph's palace is being rebuilt as part of the National Hauszmann Program. In the Middle Ages, the western entrance to the Castle was called the Jewish Gate, and not by chance: during the time of King Béla IV, who also founded Buda, in addition to the many nationalities, a Jewish community also arrived in the new city, which settled in this place, today's Szent György (first known as Zsidó [Jew in Hungarian]) Street. As Borbála Czakó tells, they may have been Ashkenazi Jews who came to Várhegy at the invitation of Béla IV. The Jewish residents, mostly engaged in trade, money transactions, tax and customs leasing, contributed to the reconstruction of the country, which had been devastated and weakened during the Tatar invasion.

Their leader may have been the Viennese-born Henel comes, it was probably through his intervention that the king issued the privilege letter in 1251, which granted them significant rights.

The members of the community built their religiously important structures, the mikveh (or ritual bath) and the synagogue. The former was discovered during the excavation of the area that began in 1998, and is a real sensation, as it is the oldest, intact ritual bath in Hungary. The remains of the previously accessible mikveh will be accessible again after the reconstruction of Archduke Joseph's palace. According to archaeologists, the synagogue, which stood directly next to the former Jewish gate, and whose remains are located under today's Palace Street, is similar to the Old-New Synagogue in Prague, which is still standing today. The building, says Borbála Czakó, was demolished at the beginning of the 15th century, due to the large-scale palace construction of Sigismund of Luxemburg. At that time, the entire Jewish quarter was moved to the opposite side of the Castle, to today's Táncsics Mihály Street.

The Vatican embassy once operated in the historic yellow palace at 4–5 Dísz Square, where Angelo Rotta, the papal nuncio, saved thousands of Jews during the Holocaust (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

However, before we get there, we take a big leap in time and introduce the less well-known, but all the more important 20th-century locations. Our first stop is at 4-5 Dísz Square, in front of the characteristically "monumental yellow" house in which the papal nunciature operated between 1922 and 1945. A memorial plaque placed on the wall of the house in 1992 announces that the apostolic nuncio Angelo Rotta worked here between 1930 and 1945. He was the first among the ambassadors of neutral countries in Hungary to speak out against anti-Semitic laws and efforts, and then he acted against them: after the deportations began, he issued countless safe conduct cards, so-called schutzpasses, to those in need, ensuring that their owners were under the protection of the country in question. According to estimates, the number of safe conduct papers issued between the walls of the house can be between 13 and 19 thousand, and in addition, about two hundred persecuted people were hidden in the building until the end of World War II.

In 1944, the intelligence officer of Hitler's Germany, Wilhelm Höttl, took 27 chests worth of art treasures with him from the house at 7 Dísz Square, which has been beautifully renovated (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Almost adjacent to the nunciature's former palace, the beautifully renovated citizen's house at 7 Dísz Square also keeps secrets. After the German occupation, Wilhelm Höttl, the representative of Nazi intelligence in Hungary, moved into the magnificently furnished house, which was originally owned by Lajos Schulhof, a Jewish landowner and winemaker born in Szatka. Since a good part of the intelligence officer's work - as Borbála Czakó puts it - "took place at the dinner table", countless influential people visited Höttl, since everyone knew that the shortest route to Heinrich Himmler and Adolf Hitler led from here. Who was the most notorious guest of the house, about whose visit Höttl testified in the Nuremberg trial?

The intelligence agent was transferred to Sopron in November 1944, but before that Höttl had 27 wooden chests made by a carpenter from Úri Street, and he left Budapest together with art treasures stolen from Lajos Schulhoff and other Jewish residents of Buda. After World War II, an investigation suitable for a crime novel was started after the stolen valuables, the threads of which led to Austria.

The house of the Berg Family preserves the memory of one of the best-known rescuers, the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The next stop on our walk, the building at 15 Úri Street, preserves the memory of the most famous rescuer, Raoul Wallenberg. The Swedish diplomat, like the papal nunciature, saved thousands of persecuted people with the help of schutzpasses. Wallenberg, who mysteriously disappeared at the end of the war, visited the building several times, where members of the Berg Family hid many people, such as Nobel laureate Albert Szent-Györgyi, who participated in the resistance movement. The basement of the house also preserves interesting memories: the money allocated by the Swedish state for rescue activities, as well as Wallenberg's documents and notes, were kept in the iron cassette there. Gloria von Berg, a descendant of the Berg Family displaced from the building by the communists, returned home from American emigration and bought the former family home back from the Hungarian state after the regime change.

The former home of the Zwack family, at 45 Úri street, has a special, staggered facade that follows the line of the medieval plot borders (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Although everyone knows Zwack Unicum, which is now considered a Hungarikum, fewer people know that part of the family that founded the company lived in Buda Castle at 45 Úri Street between the two world wars. Péter Zwack, who bought back the once nationalised factory after the regime change, also lived here as a child. Although Péter was a Catholic, he and his family were persecuted after 19 March 1944 because of their Jewish origin. The family miraculously survived the war: they found refuge in the house of his father's brother, Mici Zwack, on Gellért Hill, next to the Swedish embassy. They never returned to their house in the Buda Castle.

The yellow building is the former Hatvany Palace, which, at the beginning of the 20th century, was visited by most of the famous writers and poets of the time, Thomas Mann was also a recurring guest here (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The house at 7 Bécsi kapu Square was once the property of the wealthy patron and writer, baron Lajos Hatvany. In 1932, Hatvany moved into the small palace with his second wife, where he ran a literary salon - this is indicated by the names of poets and writers that can be read on the pavement in front of the building. Many important Hungarian and foreign artists of the time visited the building, among them the most famous guest was Thomas Mann. Sensing the approach of the dark times, Lajos Hatvany sold the Bécsi kapu Square palace in 1938 and emigrated to Oxford via Paris, thus surviving the Holocaust.

In the part of the Zichy Palace plot on the Babits Promenade side stood the largest synagogue in Hungary in the 15-18th century. The remains of the Gothic building are still hidden underground (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

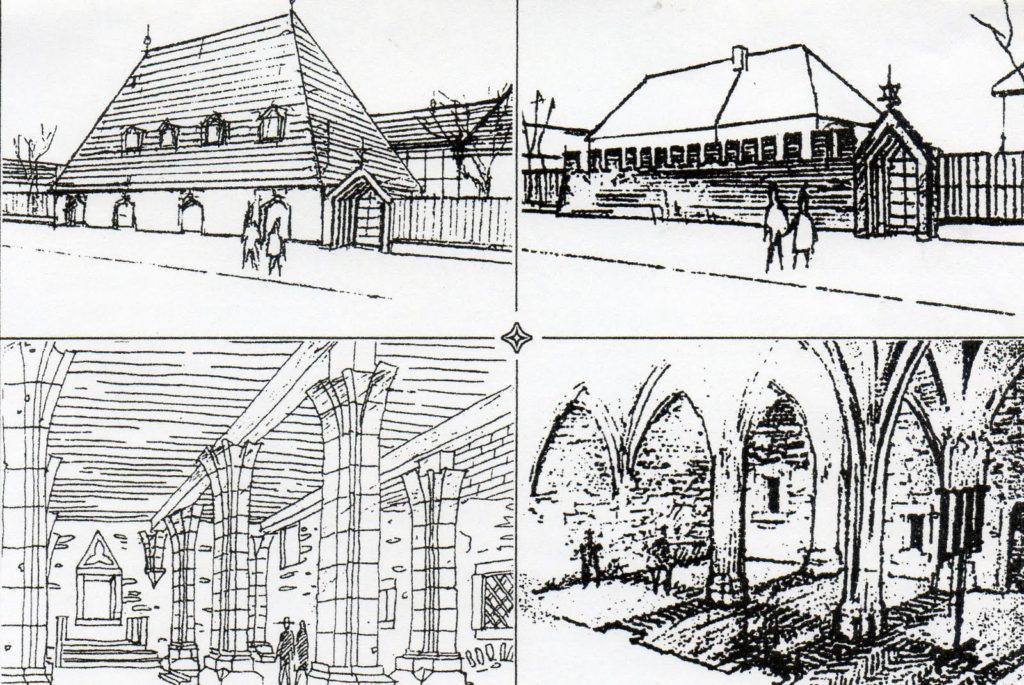

The last two sites of the walk present the medieval and modern sites of the Buda Castle Jewry, which are almost adjacent to each other. The Jewish community relocated from the southern part of the Castle in the 15th century and moved to the northern part of today's Táncsics Mihály Street. The back part of the Zichy Palace at 21–23, facing the castle wall, and under its garden, Hungary's largest Gothic synagogue is hidden, which stood from 1461 until the siege of 1686 and served the Buda community.

Exterior and interior depiction of the synagogue by Aurél Budai (Source: szombat.org)

When the Castle was taken, says Borbála Czakó, the invading soldiers began a terrible killing and looting, which we also know from the later narration of an eyewitness, Izsák Schulhof. According to Schulhof's report, the Jews who sought refuge in the synagogue were simply slaughtered by the soldiers. The two-nave, beautifully decorated Gothic building with an interior height of 8 meters was buried by time after the siege, and its remains were only discovered in the 1960s. The words of the chronicler were confirmed by the fact that during the excavation, the charred skeletons of nearly 70 people were found among the ruins. However, the building was not fully excavated and opened to visitors due to a lack of funds, so the ruins were reburied, and until 2016, not even a plaque indicated the location of the synagogue. Currently, the possibility of exploring and presenting the building has come to the fore again.

The ground-floor room of 26 Táncsics Mihály Street visible to the right, hides the medieval Jewish prayer house, which has been used again for religious purposes since 2018 (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Our last location connects the Ottoman-Turkish era with the present. On the ground floor of the house at 26 Táncsics Mihály Street in 1964, during a wall search, figures surrounded by Hebrew inscriptions were found: a stretched bow with a line of Hannah's prayer inside it, as well as a Star of David with the words of the Aaronic blessing. The building was a residential house in the 15th century, based on the age and character of the red paint depictions, it could have been used as a Jewish prayer house for a while during the Ottoman-Turkish era. After the historic reconstruction, the ground floor of the building became the exhibition space of the Budapest History Museum, and since 2018 it has again been used for religious purposes at the initiative of the United Hungarian Israelite Community. In addition to the premises of the synagogue, visitors can also view the medieval and Turkish-era Jewish tombstones displayed at the foot of the gate, as well as the rose-decorated keystone of the nearby Gothic synagogue mentioned above.

Above left, the drawings found in the 1960s on the wall of the medieval Jewish prayer house (Photo: Castle Headquarters)

The walk through the important chapters of the history of Budapest's Jews reveals a perhaps lesser-known face of the city, with its help houses that are well-known from the outside begin to tell stories, drawing us into the interesting, but often tragic, events of the centuries. Shalom, Buda! offers a personal experience to discover the secrets of the Buda Castle District.

Cover photo: View of Bécsi Kapu Square, with Hatvany Palace in the middle (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration