Many museums, including the Capital Museum, owe their existence to Flóris Rómer. In 1869, at the meeting of the Hungarian Historical Society, the famous archaeologist and art historian proposed that individual cities should also create museums to collect material memories of their own past. Buda, Pest and Óbuda were not officially united at that time, but in practice, the latter was already considered part of the capital, and archaeological objects from the Roman period were regularly found here. The excavations gained momentum in the second half of the 1870s after the international congress of prehistory and anthropology was held in Budapest in 1876.

Archaeologist Flóris Rómer, a supporter of the cause of city museums (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

At that time, the findings were still transported to the National Museum, although the Archaeology Committee of the Capital tried for a long time to get them to be presented to the public as well. This was finally realised only at the National Exhibition of 1885, the pavilion of the Capital hosted the exhibition. The need to collect memorabilia from later times was self-evident, and deputy mayor Károly Gerlóczy proposed the creation of a museum in his official submission in November 1885. There was also a direct cause for this: the monarch donated some items to the capital, which he used when laying the foundation stone of the cavalry barracks named after him.

Károly Gerlóczy justified the importance of the case as follows:

"The capital already has many objects in its possession, which, however, are scattered in different offices and will be exposed to loss and destruction over time if they are not taken care of properly. Taken in their entirety, these are enough to lay the foundation of the Museum, however, I believe that several objects belonging to the above categories, which are currently housed in the National Museum, but do not actually belong to its framework, will be available for the Capital Museum."

The planned museum's collection was therefore already partially available, artefacts have been brought to the capital for decades on various routes, but not as part of an organised collection. There was also the intention to organise the institution, but the implementation was more difficult: a building was needed where these artefacts would be collected and cared for. The deputy mayor realistically saw that the town hall was out of the question since they were already struggling with such a lack of space that they were forced to rent offices in several different buildings. In any case, he stated as a long-term goal that the newly built town hall has to have a place for the museum. In the current situation, however, he thought that the 1885 exhibition's Fine Arts Hall was the most suitable place to house the collection, and he also advocated negotiations for its acquisition.

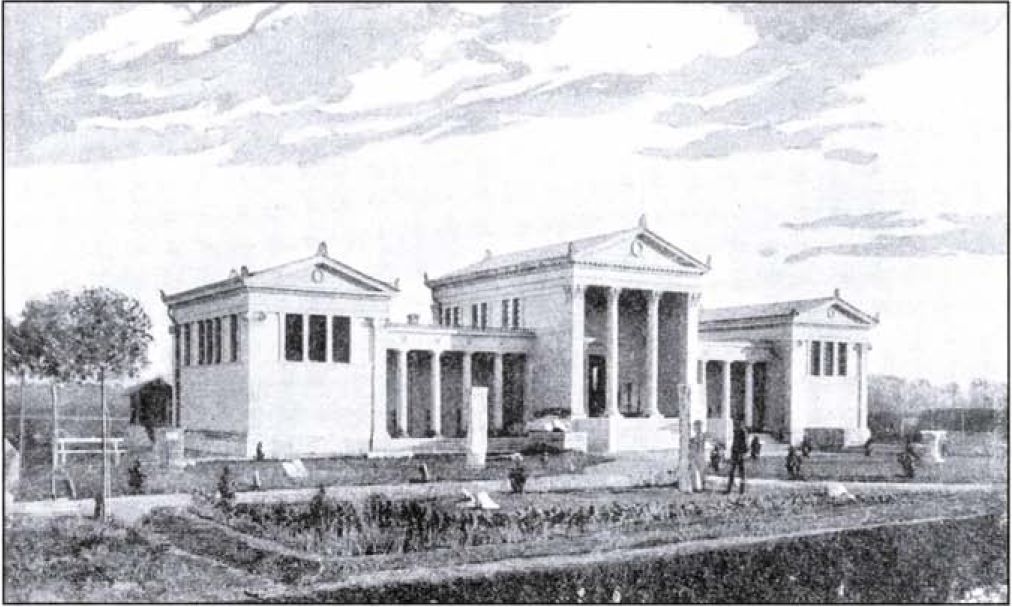

The Fine Arts Hall of the 1885 National Exhibition (Source: Fortepan/Reference No.: 31748)

On 29 April 1887, Gerlóczy's proposal was also discussed and supported by the Public Education Committee of the Capital, and this was the last step before the Council of the Capital passed a decision on the foundation of the Capital Museum on 20 October 1887, which was also signed by Mayor Károly Kammermayer, thus became legally binding. Adopting Gerlóczy's proposal, the goal of the new institution was formulated as follows:

"...such objects must be collected, professionally organised, and must be made available both for those who wish to study it and for the public, which either relates to certain outstanding events of the country's history that is more closely connected to the capital, or the special local history of the capital, or are memories of such. That is, coins, seals, documents, books, pictures, maps, flags, weapons, pieces of furniture and other objects of use that occurred in the capital during more memorable events, or were used by outstanding individuals in any respect, as well as objects that contribute to the gradual development of the capital and are suitable for indicating its current state..."

The Fine Arts Hall was also included in the decision as a location, but only as a temporary solution. The deputy mayor saw it well and actually managed to buy it from the state. It was an obvious choice, as it was built specifically for the storage of artefacts, with a correspondingly very ornate facade. Its designer was Ferenc Pfaff, who mainly specialised in railway stations, but here he demonstrated that he is at home in other building types as well. Along Stefánia Road (today's Olof Palme Promenade), the main traffic artery of City Park, he constructed an elongated rectangular building, which was decorated by powerful protrusions (risalits) at the corners and in the middle, and its central risalit was higher than the wings. Interestingly, its main entrance did not face Stefánia Road but was built in the middle of the side facing the park, which is explained by the fact that at the 1885 exhibition, this hall could only be approached from inside the City Park. During the 20th-century renovations, however, an identical entrance was also opened on the back side.

Nowadays, the Fine Arts Hall is called the House of the Hungarian Millennium (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

Following the general taste of the 1880s, Pfaff gave the building a Neo-Renaissance facade, which he covered with brick and placed many eye-catching Zsolnay ceramic decorations on it. The arched part of the semi-circular closed main entrance is filled with statues of female figures, and the designer placed vases in niches with decorative frames to the right and left of it. Smaller, square-shaped alcoves have also been created higher up, with smaller sculptures attracting attention in front of the shell background.

Decorative design around the entrance (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

In the colourful frieze under the strongly protruding main cornice, among the tendril motifs, there are portraits of famous artists in medallions, including Michelangelo, Raffaello and Leonardo. Above the cornice, the central risalit is raised by an attic, the surface of which is varied by a balustrade. The decorative system of the lower and narrower wings is the same as that of the middle tract, only there are more openings, which are also smaller. The only significant difference is that there are pairs of pillars with Corinthian capitals between them. In the corner risalits, these openings are blind - that is, they are walled up - as water flows from ornamental wells in them, thus connecting the building to the park environment. The interior has a three-nave layout, which is divided by transepts in the risalits and is thus divided into fifteen parts.

Ornamental wells were placed at the corners of the hall (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

By the end of 1887, the capital was able to organise its own museum and provide a building for it. However, in the nearly two decades that have passed since Flóris Rómer's proposal, many rural towns have done the same, bypassing Budapest: a museum was established in Szombathely and Eger in 1872, in Székesfehérvár in 1873, in Szeged in 1883, but the series could also be continued with smaller settlements such as Jászberény, Tiszafüred or Mosonmagyaróvár. Therefore, the creation of the Capital Museum became urgently necessary for purely prestige reasons. Of course, the delay was also explained by the existence of the Hungarian National Museum, since archaeological finds could be transported there, while such an option was not available in the countryside.

Bálint Kuzsinszky, the first director of the Capital Museum (Source: Katalin K. Végh: The Budapest History Museum from its foundation to the turn of the millennium)

The Capital Museum, on the other hand, had an advantage from the point of view that an experienced director was appointed to lead it: the archaeologist Bálint Kuzsinszky previously worked in the Antiquities Collection of the National Museum. He also played an important role in the excavations at Aquincum, and he fought resolutely to ensure that the valuable objects found were not taken to the National Museum's warehouse, but remained on display on site so that the public could admire them. His efforts were crowned with success, as from the autumn of 1888 the finds could be collected in the Krempl Mill. An even bigger event was that in 1894 they were able to erect a separate building in Óbuda, which was designed by Gyula Orczy and followed the form of ancient Roman churches. Due to the number of objects and the increased interest, it was soon necessary to expand the museum, which consisted of only one room, and the work was completed by 1896: it was extended with two side wings.

The building of the Aquincum Museum was completed in 1896 (Source: Katalin K. Végh: The Budapest History Museum from its foundation to the turn of the millennium)

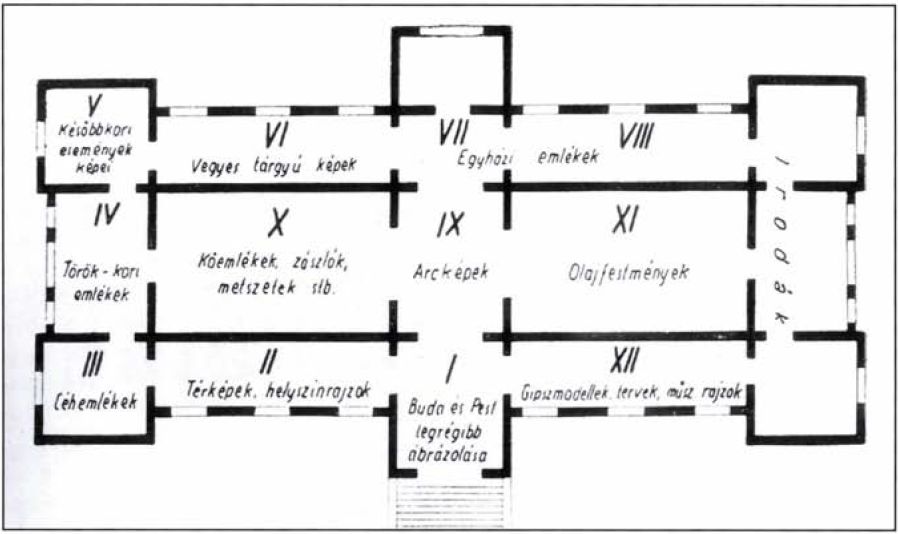

However, they could not do the same with the main building in City Park, even though it soon became clear that it was too small to store and exhibit the ever-growing collection of the capital. Although it was intended as a temporary solution, the Capital Museum finally opened its permanent exhibition here: it took twenty years since its foundation: and the big day came on 1 June 1907.

The equipment of the Museum's permanent exhibition (Source: Katalin K. Végh: The Budapest History Museum from its foundation to the turn of the millennium)

The situation, thought to be temporary, did not change for another three decades, and it was not until the beginning of the 1940s that the collection began to be moved to its current location, the Kiscelli Castle. The Aquincum Museum was not affected by this, the archaeological findings there remained in Óbuda and can still be seen there today. The exhibition locations of the Capital Museum continued to grow: in 1928, they bought the inner city Károlyi Palace, where the works of art were housed (Capital Gallery), but after World War II it was merged into the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, and in 1957 the building was received by the Petőfi Literary Museum.

The Capital Museum was given exhibition space in the Buda Castle for the first time in 1932: the medieval archaeological finds were placed in the northern tower of the Fisherman's Bastion. In 1945, they were moved to the Szentháromság Square building of the old Buda City Hall, and in 1967 – after the partial restoration of the Buda Castle – to the southern wing of the Royal Palace. The latter, i.e., the Castle Museum, is today the centre of the institution operating in several locations. The newest member is the Budapest Gallery, which organises its exhibitions on Lajos Street.

In 1936, the institution adopted the name Capital History Museum, which was changed in 1951 to the Budapest History Museum, which is still used today.

Cover photo: The Aquincum Museum (Source: Fortepan/Reference No.: 7070)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration