Gáspár Fábián was born on 2 January 1885 in Székesfehérvár, his ancestors worked in the construction industry for several generations. His father pursued longer studies in Mülhausen in Alsace-Lorraine, where his family accompanied him, so the young Gáspár started elementary school there. Upon returning to his hometown, he was enrolled in the local secondary school specialising in science, from which he graduated with excellent results. Many people noticed his excellent dexterity and tried to steer him towards an artistic career, but he also considered family traditions important, so in 1905 he applied to be an architect at the Royal Joseph Polytechnic University and was accepted.

Statue of Gáspár Fábián, work of Antal Orbán (Source: Digital Image Archive, No.: 027563)

His teachers were such excellences as Dezső Hültl, Alajos Hauszmann, Frigyes Schulek, Virgil Nagy or Sándor Aigner. They all worked in historical styles: the first two mainly in Baroque and the latter in Romanesque and Gothic. Fábián was the first to apply as an assistant to Aigner, so he participated, for example, in the design of the Church of Perpetual Adoration of Erzsébet. He obtained his degree in 1908, after which Virgil Nagy invited him to be his assistant, with whom he worked for two years.

He learned a lot from the excellent masters, as evidenced by his competition successes: in 1910, for example, he received a travel scholarship worth 1,200 koronas from the Ministry of Religion and Public Education. He used this great opportunity to tour Italy. When he returned home, he already received commissions (for example, the high school in Jászápát, the orphanage in Székesfehérvár), so he started a family with a secure existence behind him: he got married in 1911, his wife was Anna Horváth, who gave her husband seven children, giving birth to six sons and a daughter.

Church of Perpetual Adoration of Erzsébet (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

However, the family’s happiness did not last long, history intervened: the energetic Fábián was drafted into the 4th pioneer regiment in Budapest at the outbreak of World War I and was sent first to the Serbian and then to the Russian battlefield. He served at the front for nearly a year without interruption and was promoted to first lieutenant for his merits. Although he was not injured, the merciless conditions even took a toll on his health: typhus knocked him off his feet. He was treated in the hospital for more than half a year, and then declared disabled, so he did not have to fight for the rest of the war.

Fábián's not only physical but also mental strength was second to none, he had an enormous work ethic and used it to his advantage. After his recovery, he began to study and work at the same time: he returned to the University of Technology, where he obtained a degree in economic engineering in 1918, and two years later he received his doctorate. At the same time, he took on every job that was offered to him: he designed stations for the Szentendre-Visegrád railway line or university buildings for the newly founded campus in Debrecen. But in addition to his architectural activities, he taught at the Felső Építő Industrial School and was the editor of the economics section of the Új Lap magazine.

The Felső Építő Industrial School is now the Ybl Miklós Faculty of Architecture of Óbuda University (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

Journalism was not far from him before, he regularly published in Építő Ipar from 1910, but in 1920 he was also entrusted with the duties of editor-in-chief, which he naturally did not say no to. This extraordinary capacity did not escape the attention of politicians, and the post-Trianon governments took him under their patronage: he received the most commissions from József Wass, who was Minister of Culture between 1920 and 1922 and then became the head of the Ministry of Welfare and Labour. In this way, Fábián ended up designing a number of medical institutions: for example, the Angyalföld Mental Hospital and the Madarász Viktor Street Children's Hospital in the capital, but his buildings in the countryside were much more important, such as the public hospital in Nyíregyháza, Kisvárda, and especially in Szekszárd.

He maintained good relations not only with the government but also with the Catholic Church and various religious orders. Even before the war, the Jesuits entrusted him with the design of their novice house and chapel in Érd, and the expansion of the convent of the Sisters Our Lady of Sion in Törökbálint also belongs to the same period. In Dombóvár, he built a school designed for the Order of Saint Ursula in 1912, a church for the Jesuit Order in Mezőkövesd, and in Rákospalota he transformed the Clarisseum institute designed by Miklós Ybl into a Salesian school in 1924.

Saint Margaret High School in 1935 (Source: Fortepan/No.: 21577)

His main work in Budapest is also a monastic school, which was designed in 1930 on behalf of the Sorores a Divino Redemptore (Sisters of the Divine Redeemer) and is known today as Saint Margaret High School. It stands at the beginning of Villányi Road (5-7 Villányi Road) and this sumptuous Neo-Baroque building attracts attention from afar. Its style is also reflected in the floor plan, which is very busy: the long, central tract is joined at each end by a shorter wing, which extends both forward and backwards, thus actually forming a flat letter H. Its entrance opens from the central part of the building in a projection (avant-corps), which is enclosed by a columned gate structure (so-called portico). The avant-corps is crowned at the top by a broken, characteristically Baroque pediment, behind which rises the slender dome, which is the symbol of the building. A beautiful decorative hall was also created inside. The construction of the building fell during the years of the World Economic Depression, but despite the many difficult circumstances, it was completed by 1933. Here, Fábián found the golden mean of how to adapt the otherwise rather expensive Neo-Baroque style to tight financial conditions.

The hall of Saint Margaret High School in 1935 (Source: Fortepan/No.: 21573)

Parallel to the high school, however, he designed his three churches in Budapest in medieval styles, because, in people's minds, this era was mostly associated with the Catholic Church. In the very difficult conditions between the two world wars, many churches had to be built in Budapest, because during the dualism their number did not keep up with the intensive growth of the population. The church's money was thus divided among the many locations, each building received less, which is also reflected in their external appearance.

In addition, the Holy Family Church in Terézváros (1930-1931, 67 Szondi Street) had to be built in a very unfavourable location, on a narrow lot sandwiched between residential houses, so it was not possible to count on a really magnificent result from the start. Fábián actually made the most of the given situation here, considering the circumstances: he enlivened the monotonous image of Szondi Street with a fresh splash of colour. Its style can also be said to be special, as the designer used the Tudor version of Gothic, developed in England, which is relatively rare in Hungary. It is not typical for it to be high rise, and the top arches are also more depressed - this actually suited the location, since a really steep tower would not have been able to prevail here. For this reason, two lower towers were erected in front of the facade of the building covered with brown sandstone. Between them, the entrances open from two Tudor-arched vestibules, above which a huge glass window ensures an adequate influx of light.

The Church of the Holy Family in Szondi Street (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The Church of the Holy Cross, built in 1930 in the outer part of Ferencváros, at the junction of Üllői and Ecseri Roads, was also largely determined by the difficult conditions between the two world wars. During World War I, barrack hospitals were established in this area to care for wounded soldiers, and in the twenties, they were used to create emergency housing for the masses who fled to Budapest. This was the infamous Mária Valéria housing estate, the biggest slum in the capital. There were a lot of people living here, who also needed increased spiritual care, so it was clear that a large church had to be built. For this reason, the designer extended the three-nave church in front of the sanctuary with a transept, although its legs are relatively short. On the other hand, the two towers on the edges of the main facade are very tall and attract attention from afar. The structure of the building is defined by reinforced concrete pillars, which, however, do not appear on the outside, Fábián covered it with brown sandstone and designed it in a Neo-Romanesque style. The somewhat gloomy exterior is offset by a richly decorated, colourful interior.

The Church of the Holy Cross at the intersection of Üllői and Ecseri Roads (Source: hu.wikipedia.org)

Fábián also drew up the plans for the Church of Saint Vincent in Middle-Ferencváros, at the intersection of Haller and Mester Streets, in 1930, but here the crisis intervened more seriously and construction could finally start only five years later. It was worth waiting for a more favourable financial climate because this way they were able to build a huge church capable of accommodating two thousand people. It has a longitudinal layout, but its three naves are also intersected by a spacious transept, as a result of which its floor plan forms a beautiful Latin cross. To the right of the aisle is the tower, which is also impressive in size, 55 metres high, and its peaked top further emphasises the height. By the way, semicircular openings are characteristic of the facade, as the Romanesque churches of northern Italy floated before the eyes of the designer. In addition to the stubby pillars of the entrance hall, the rose window dominating the centre of the main facade shows this beautifully.

Church of St. Vincent's at the intersection of Mester and Haller Streets (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

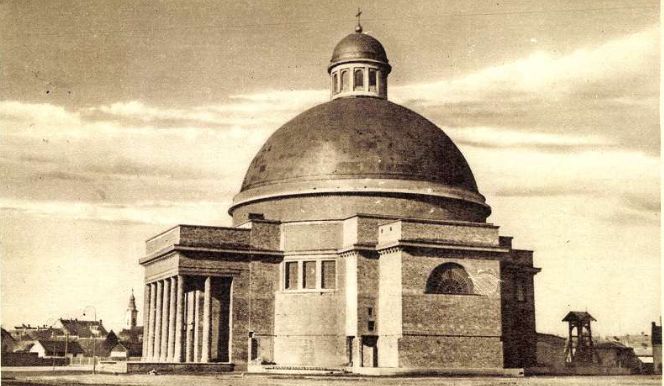

Gáspár Fábián, a lover of historical styles, also had a good understanding of Classicism, the most illustrious example of which is the memorial church of Ottokár Prohászka in Székesfehérvár, consecrated in 1933. The central building is crowned by a huge hemispherical dome, which is entirely made of reinforced concrete and is the largest building of its kind in the country. Its entrance opens behind a six-column, monumental gate, which also indicates that its prototype was the Roman Pantheon. Fábián designed more than fifty churches throughout the country, but he considered this one to be his masterpiece. He was proud that he could create such a worthy building for the esteemed former bishop of Székesfehérvár, in his own hometown.

The memorial church of Ottokár Prohászka in Székesfehérvár (Source: hungaricana.hu)

No matter how strong his immune system was, his incredible work rate backfired on him and in August 1936 he suffered a stroke. Fortunately, he recovered without permanent damage, but after that, he did not work as much, and his creative period came to an end when he retired in 1938. He devoted the last decade and a half of his life to his large family, among whom he died on 13 January 1953. He was laid to rest in the garden of the memorial church of Ottokár Prohászka, where a statue was erected for him in 1990.

Cover image: The Saint Margaret High School in 1935 (Source: Fortepan/No.: 21577)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration