Imre Madách and Sándor Petőfi were born in the same year, in fact, both in January. Petőfi on 1 January, Madách three weeks later, on 21 January. Yet, for many, it seems as if they lived in two different ages, which may be due to their different oeuvres. In addition to the same month of birth, they were also connected in that they were both in love with ladies with whom Menyhért Lónyay, the Minister of Finance of the Andrássy Government of 1867 and later prime minister (who was also born in January, only a year earlier, in 1822) was also closely related to.

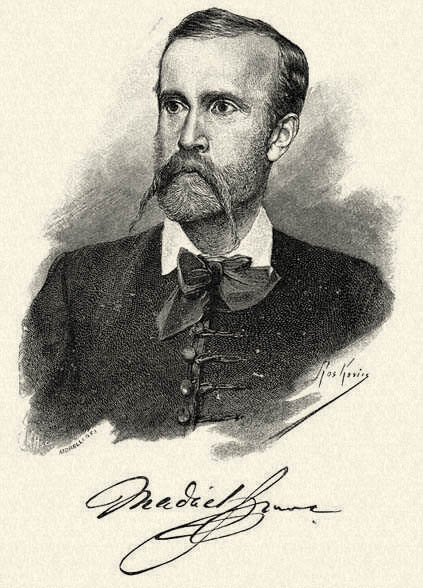

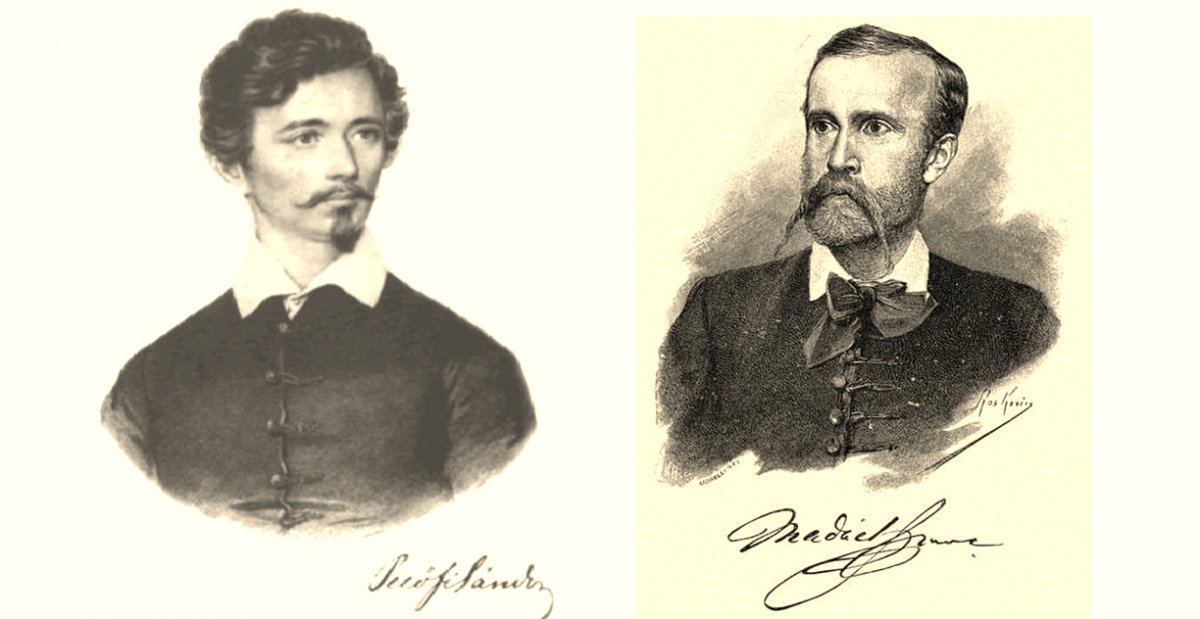

Woodcut of Imre Madách by Gusztáv Morelli. Published in the Az Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia írásban és képben [The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in writing and image] (1887–1901) (Source: Wikipedia)

Miklós Barabás: Sándor Petőfi, 1845 (Source: Wikipedia)

Lónyay and Madách began their higher education in Pest in 1837, both studied at the Faculty of Humanities and then at the Law Faculty of the University of Pest, and among their classmates were many students who later went on to have significant careers. For example, the first prime minister of dualism, Count Gyula Andrássy, and his brother, Manó Andrássy, also referred to as the Iron Count, who was involved in the development of domestic iron ore mining and metallurgy, studied together with them.

Lónyay and Madách were close friends, behind which was their interest in literature, during their university years they edited a manuscript magazine called Mixtura. Writing was not far from Lónyay either, but due to Madách's criticism, he abandoned his attempts to write poems and plays. Later, however, he took up his pen several times on economic and political issues and published several works on this topic. During their university years, Lónyay and Madách often went to the Vigadó to the concerts of the Musikverein or to the halls of the National Casino, which was then still based in the Lloyd Building, where they listened to art-loving string quartets and string quintessences. In addition, they did not miss the performances of the Hungarian Theatre of Pest (National Theatre from 1840), which was opened at the beginning of their university studies, although Madách's mother feared for his son of this comedic life, lest her son gets into bad company.

The central building of the Royal University of Pest at the beginning of the 19th century (in today's Egyetem Square in the city centre) on Leopold Zechmeyer's section. Madách and Lónyay and the Andrássy brothers: Counts Gyula and Manó studied here (Source: ELTE ÁJK)

At that time, the Lónyays lived in the Greek Palikucsevni House, located close to the university, on Egyetem Street, opposite the seminary church (today's University Church or Church of St Mary the Virgin), and Madách lived in the Szákáll House on Széna (today Kálvin) Square not far from here. The house was presumably once located at today's 1 Kálvin Square, but Madách's classmate Béla Kámánházy, in his recollections, identified it with the later house of Samu Németh (today's 1 Baross Street, 2-4 Üllői Road; in the 1870s, 11 Kálvin Square).

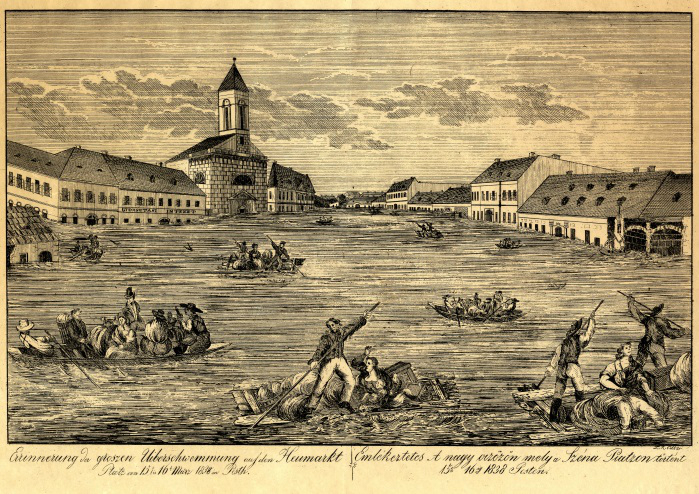

Thus, Madách, who had an aloof nature but was intellectual, spoke many languages, studied music and painting, and was blessed with wit and good intellectual abilities was a welcome guest at the Lónyays, who were among the respected and influential residents of the city at the very end of the 1830s. Menyhért Lónyay's father, János Lónyay, played a major role as a royal commissioner in the rescue and reconstruction works of the 1838 flood.

The former Széna Square (now Kálvin Square) during the 1838 flood. Madách lived in the Szákáll House on Széna Square when he was studying in Pest

János Lónyay, father of Menyhért Lónyay (Source: Wikipedia)

Menyhért Lónyay in 1848, at the age of 26 (Source: Wikipedia)

This close friendship made it inevitable for Madách to meet Menyhért Lónyay's sister, Etelka, for whom the young poet fell in love. Thus, it is not surprising that Madách spoke with incredible happiness about the evening with the participation of Etelka Lónyay, a carnival dance party organised by János Lónyay in January 1840 for his son Menyhért, who was on the verge of adulthood.

Menyhért Lónyay invited many guests and friends to this occasion, including his best friend and fellow student, Imre Madách, who wrote about this event to his sister, Mária Madách in poetic language, with a preface and a poetic motto, almost ecstatically. Madách started getting ready at 4:00 p.m. so that he could appear at the party elegantly, in the "best edition", and that every (dress) wrinkle and every button would be on him according to the most precise arrangement. What is more, he did not disdain intense scents on this occasion either, he sprayed himself with Patchouli perfume, which became fashionable in Europe in the 1840s, and he arrived at the ball "like a fragrant spring zephyr" towards the young ladies - as he wrote in his letter - "towards the flowers ".

Spiced up with refreshments, ice cream and cakes, pâtés and salads, the evening consisted of several dance programs. Among the latter, the cotillion was the most memorable for Madách, which he managed to dance with Etelka Lónyay despite difficult struggles, while he did not even think of asking other girls to dance the whole evening.

Cotillion towards the end of the 18th century, on an etching by Antoine-Jean Duclos (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

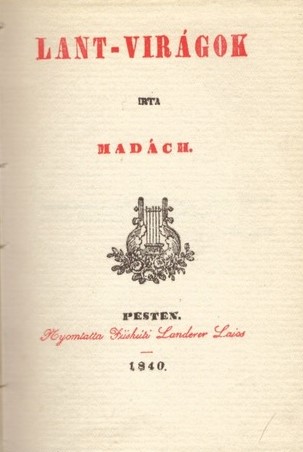

Etelka Lónyay, however, did not reciprocate the poet's feelings, which Etelka's other brother, Albert Lónyay, somewhat disparagingly evaluated as just a simple student love, which always existed and will always exist among young people going to school. On the part of Madách, however, it was probably not just a simple flare-up, according to the tradition of literary history, this love, Etelka, who became the muse, inspired Madách's first book of poems, published in 1840 under the title Lantvirágok.

After a very memorable ball in Madách's life, a few years later, on 6 August 1844, Etelka gave her hand to the landowner Ödön Szirmay, with whom she had several children, but their marriage did not last long. It ended in divorce, and the woman went back to using her family name. People could say they were kindred spirits with Madách. Etelka herself loved art, wrote some short stories, published the memoirs of her mother, Jánosné Lónyay born Florentina Lónyay, translated from German, and also painted flower still lifes. She died in Újpest in 1896. Madách, after Etelka's marriage, got married in 1845, but the marriage with Erzsébet Fráter also ended in divorce nine years later.

Madách's book Lantvirágok, published in 1840

The other hero of the story, Petőfi, was no luckier than Madách in terms of youthful love, although he was not in love with Lónyay's sister, but with the lady whom Menyhért Lónyay courted. The lady's name was Emília Kappel, and she was the daughter of Frigyes Kappel, a wealthy wholesaler and banker of the time. Kappel had an office in Bálvány Street (today's Október 6. Street) and a prestigious house at today's 19 Váci Street, where Károly Kisfaludy and Mihály Vörösmarty lived at the same time, but not only did they lived but also died here in this house.

.jpg)

A plaque on the wall of the house reminds us of the death of Kisfaludy and Vörösmarty (Photo: Zsolt Dubniczky/Pestbuda.hu)

.jpg)

Nowadays, a multi-storey, modern building stands on the site of Frigyes Kappel's former house on Váci Street (Photo: Zsolt Dubniczky/Pestbuda.hu)

The daughter of Frigyes Kappel was the celebrated beauty of Pest, an eye-catching creature whom Petőfi noticed at one of Liszt's concerts in the 1840s, perhaps not for the first time in the city. The poet's friends noticed that the attention of Petőfi, who supposedly did not really like musical pieces, was not captured by Liszt's melodies, but by the enchanting beauty of Emília Kappel sitting in the lodge.

Of course, social differences existed even then, which Petőfi's friends drew the poet's attention to. "She is not for our kind of poor lad," said Kálmán Lisznyai, a poet also born in the same year as Petőfi. However, Petőfi was a fierce, fiery-natured man, who was hurt by this speech that did not befit a self-confident person, and he wanted to show his friends that he was a brave man and that wealth and social barriers did not prevent him from asking the rich banker for his daughter's, Emília's hand.

He went to see him at 19 Váci Street, where he presented his intentions to the banker: he asked him for his daughter's hand in marriage. Frigyes Kappel was a polite, well-mannered person who knew and appreciated Petőfi's works. He did not kick out the ardent poet, but tied the engagement to his daughter's consent, asking if they had already talked about it. Petőfi admitted that they had never spoken to each other in their lives, to which the banker believed that he should win his daughter's affection first.

Emília Kappel (Source: Wikipedia)

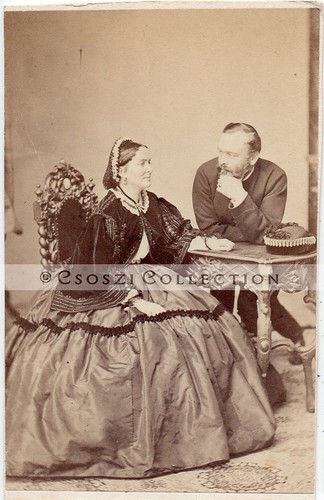

Of course, the proposal did not end in marriage. It is well known that Petőfi married Júlia Szendrey in 1847, and Emília Kappel said the happy yes to Menyhért Lónyay two years earlier, in 1845, with whom Lónyay was married for forty years until his death in 1884.

Emília Kappel and Menyhért Lónyay

Cover photo: Portrait of Sándor Petőfi and Imre Madách

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration