Frigyes Spiegel was born in Pest in 1866 when the city began to develop rapidly. His technical interest led him to the field of architectural engineering, which offered a secure livelihood in the midst of the construction fever. He graduated from the Royal Joseph Polytechnic University in 1887, then worked with Vilmos Freund, but also occasionally worked for the architect duo Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer, who became famous for their theatres.

After six years of experience, in 1893 they founded their own office together with Fülöp Weinréb. During their collaboration, Spiegel prepared the plans, his partner was responsible for obtaining the orders and the construction of the buildings. At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, several residential buildings were built in this way, the facades of which Spiegel first designed in Neo-Baroque and then in Art Nouveau style. They became really famous for the latter, as they were the first domestic representatives of the style: already in the second half of the 1890s, they transferred the colourful plant, animal and human figures that had recently appeared in Western Europe to their own creations.

The Lindenbaum House at 94 Izabella Street is Spiegel's first Art Nouveau work (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

After more than a decade and a half, the office was disbanded, and in 1909 Spiegel established a joint venture with Géza Márkus. This was not so long-lived and in 1912 Károly Englerth became Spiegel's new colleague. Their collaboration was interrupted by history: after the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic - in which he took an active role - he emigrated to Nagyvárad (Oradea, Romania) in 1919, like many left-wing artists. At that time, the city was already under Romanian occupation, so he was able to avoid being held responsible by the Hungarian authorities, yet he did not have to leave his homeland far away. He stayed in the "Paris of the Körös Banks" for only five years, returning to Budapest in 1924.

At home, completely changed circumstances awaited him: in the mutilated country, understandably, a conservative public mood prevailed. The government blamed the liberal spirit of the previous decades for the loss of the country, which was identified with Art Nouveau in the arts. There was no more room for playful experimentation, and well-known styles radiating security had to be used in architecture. After the country got back on its feet, this strictness began to loosen by the end of the 1920s, so more and more people returned home from abroad. Together with the artists, newer styles that were spreading in the West at that time also entered the country, where they quickly found a breeding ground.

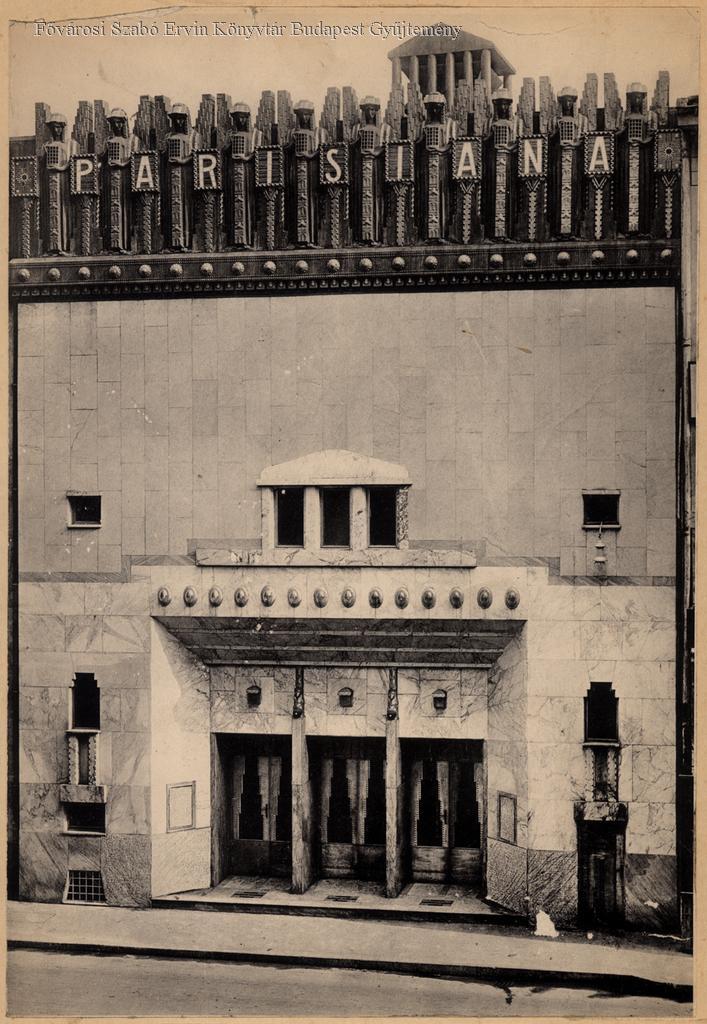

The place of amusement, Parisiana built according to the plans of Béla Lajta (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

According to the latest fashion, the facades were decorated with broken lines in different ways - for example, in a gradual or V-shape - and this is how the trend got the contemporary name of zigzag decoration. In the 1960s, a special term began to be used for it: it became Art Deco. In fact, gradual or staggered forms had already appeared on buildings in Budapest before, Béla Lajta, who was usually beyond his age, decorated the Parisiana at 35 Paulay Ede Street in the 6th District (1907–1909) similarly even before World War I. The female figures standing between the crenellations may bring to mind the influence of Cubism, and the geometric shapes decorating their clothes may remind us of the ancient Middle East.

Even between the two world wars, Art Deco can be recognised mainly in the forms of detail: rather, it was rampant in the applied arts, and relatively few buildings were completely realised in this style. According to the research of András Ferkai and Zoltán Bolla, it was strongly mixed with the three defining architectural trends of the period: conservative, folk-national and modern. The first actually means the continuation of historical styles, mainly Neo-Baroque in the Horthy Era, the second refers to the buildings of Károly Kós and his colleagues, while the third refers to functionalist architecture (e.g. the Bauhaus). Bolla briefly introduced the style as follows:

"The Hungarian Art Deco building stock does not even reach a tenth of the Art Nouveau one, and it did not define the image of Hungarian cities - with the exception of a small part of the 11th District. […] In the second half of the 1920s, plant ornaments dominated, at the end of the decade the Cubist-Expressionist gable and wedge forms, which were replaced around 1930 by the horizontal banding of the facades, so that a few years later this architecture also faded into the uniformising form language of modernism.”

Frigyes Spiegel was also captivated by this decorative trend, and he designed a fully Art Deco building at 19 Pannónia Street in Újlipótváros. In fact, he did not work alone even then, he and his young colleague, Endre Kovács, ran a joint office. Kovács probably won the commission this time as well, which was not a particularly difficult task, since the development of the district gained momentum between the two world wars.

Újlipótváros is located outside the Outer Ring Road, but the urban development plan also affected this area: residential houses were planned here. This part of the ring road was built the latest, it was handed over only in 1896, and that was when the emblematic building of the district, the Comedy Theatre of Budapest, also opened its doors. Some Art Nouveau residential houses were already built at the beginning of the 20th century, of which the so-called Palatinus houses designed by Emil Vidor (1911) are the most significant in terms of the cityscape. However, the large-scale construction of residential houses was postponed until the end of the 1920s, the Budapest Public Works Council decided in 1928 to establish Szent István Park on the site of a former parquet factory.

Skyline of Újlipótváros with the Palatinus houses in the background, 1912 (Source: Fortepan/No.: 53617)

The construction fever therefore also extended to Pannónia Street, which runs slightly inland from the river, where the architect duo designed a five-story residential house. Its facade was covered with bricks following Northern European patterns, as this had been the custom around the North and Baltic Seas for centuries. In Spiegel's building, in addition to the brick, the artificial stone elements carry the Art Deco spirit: especially the gate and the two huge closed balconies.

The gate of the residential house at 19 Pannónia Street (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

The relatively modest entrance is surrounded by a wide and tall frame: pillars divided by vertical grooves on both sides support the boldly projecting cornice, which also carries two spheres on its edges. The real interest of the gate, however, is the field (lunette) between the hood moulding and this ledge, which is netted by lines that break at an angle, resulting in a sort of labyrinth. This motif can also be interpreted as a continuous line formed from the ancient lucky symbol, the so-called swastika. The artificial stone frames of the windows are much narrower and undecorated, although the one above the gate is also crowned by a statuesque hood moulding.

The main attraction of the facade is clearly the two closed balconies spanning three levels. Their surface is decorated with lines that break at an angle in the same way, but they are more orderly, and in fact, they actually wind symmetrically around the edges of the balconies, as well as below and above the windows that open here. Among the lines, stones with a rectangular ground plan - so-called diamond blocks - rise from the surface of the balconies, which also orderly surround the windows. Art Deco is also represented by the step-closing gable, on top of which a festoon runs along, giving the building a somewhat exotic-oriental look.

The main facade of the building features many Art Deco style features (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Frigyes Spiegel - whose German surname means mirror in Hungarian - therefore presented Art Deco lavishly after the Art Nouveau, and the residential house on Pannónia Street reflects the characteristics of the style. The building was handed over in 1929 and it was the penultimate creation of the master. The architect's life, rich in masterpieces, ended on 26 February 1933.

Cover photo: Residential house at 19 Pannónia Street (Photo: Balázs Both/pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration