The people had requested a bridge in the city centre of Budapest since the mid-1880s. A tender was announced for the bridge in 1893, but the construction was postponed, among other things, because the Pest bridgehead would not fit between the houses of the densely built-up city centre.

Most of the Pest riverbank in the area was eventually demolished with the construction of the bridge. But even before that, in 1895, 125 years ago, János Ruppenthal came up with a special proposal. If his plan came to fruition, it would probably have provoked the same controversy as the Eiffel Tower, the iron monster "temporarily" erected in the middle of the French capital.

The analogy is justified because, like the Paris tower, this idea dreamed up a huge lattice iron structure, but it would not only have been a tower but also a huge arch bridge connecting Pest and Buda.

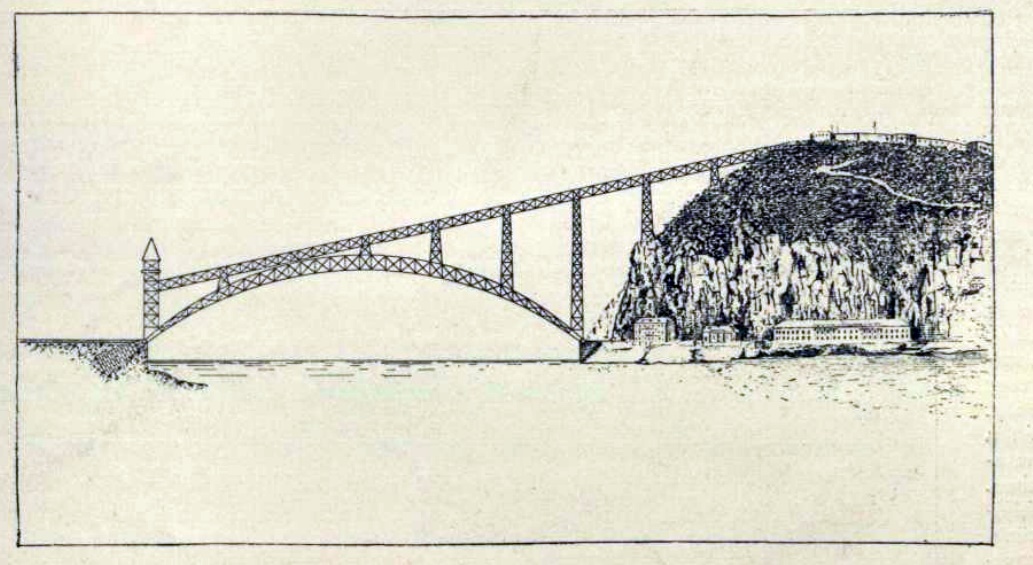

Ruppenthal's Plan (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 26 May 1895)

The bridge would also have solved the problem of climbing Gellért Hill, as the Buda endpoint would not have been anywhere other than on the top of the hill. Furthermore, the bridge could have been used by pedestrians and also by a funicular.

János Ruppenthal wanted to build his crossing for the upcoming millennium celebrations. Of course, such a bridge would not have served daily traffic. It was specifically aimed at tourists and foreign and domestic visitors, all those who wanted to admire Budapest from a height. As stated in the 26 May 1895 issue of the Vasárnapi Ujság:

“The designer thinks this sloping bridge would be very profitable. Because notwithstanding that the relevant audience would surely use it all the time, many strangers would visit Budapest just to see this unique funicular, just like they visit Paris for the Eiffel Tower, or Chicago for the Ferris wheel. Furthermore, Gellért Hill could be used much better than it has been so far. The main profit would be in the economic and aesthetic sales of the hill.”

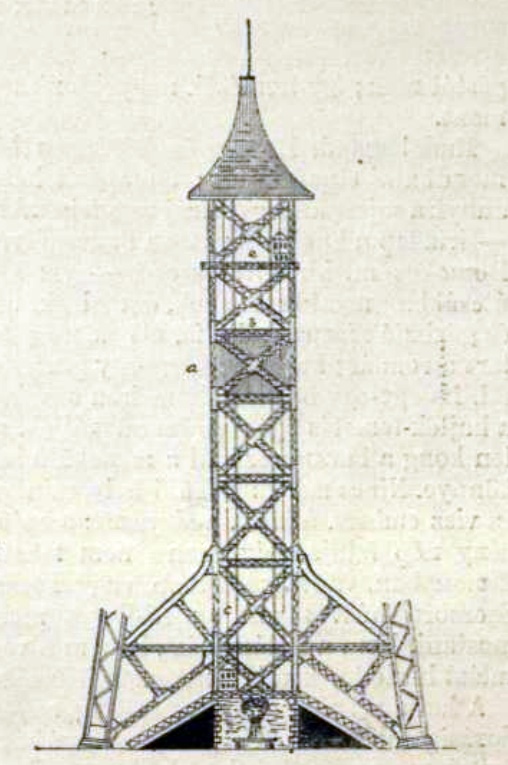

Ruppenthal's solution combined the missing bridge and the Gellért Hill funicular as follows: in Pest, a tall iron tower would have been erected, inside which passengers could have reached the bridge itself. In addition to the stairs, a lift was planned for the multi-storey high tower.

The tower on the Pest side where would have been an elevator and stairs (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 26 May 1895)

The bridge structure would have been a single-span, 300-metre-long arch bridge, which in its day would have set a world record if it had been built since no such arch bridge had been built anywhere at that time. Similar structures did not reach the 200-metre opening even then. The huge iron arch bridges of the age, the Luís I Bridge in Porto or the Garabit Viaduct had an opening of “only” 165-172 metres.

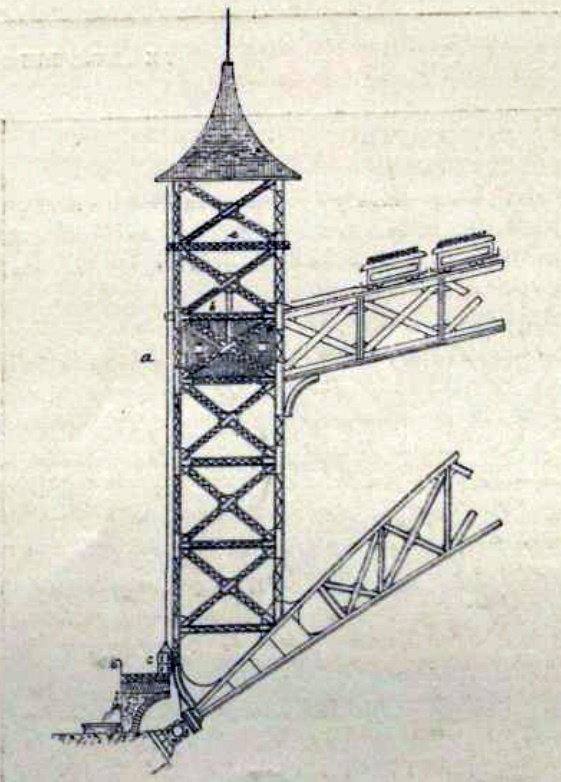

Thus, the road would have started high above the city, but the Pest tower would not have reached the height of Gellért Hill. The road would have risen straight from the Pest side to the Buda endpoint. There would have been a funicular on the bridge. Since there is no engine in the cars of the funicular, as the cars are towed by a cable moved by an engine, the gas engine would have been housed in the Pest Tower.

Pedestrians could have crossed the Danube in the middle of the bridge, between the two tracks. So those who wanted to get to Gellért Hill could go up stairs and on foot, or by elevator and funicular.

According to the designer, the great advantage of this solution would have been that it would not have hindered navigation and water flow, as there would have been no need for pillars in the river. Up to 3-4 thousand people could have reached the hill in 10 hours across the bridge, at least according to the proposal.

Detail of the tower and the track, the dimensions are well illustrated by the size of the funicular cars on the bridge (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 26 May 1895).

However, one thing was very much missing from the draft: money. The designer wanted to start a public limited company, but it failed.

In fact, the bold idea did not have much chance of being realized, as the plans for the Erzsébet Bridge had already been prepared in the bridge department of the ministry, and the reconstruction of the city centre was also decided.

Take a look at the pictures: the structure would not have been beautiful, but rather shapelessly large and rugged, and probably unfeasible with the technology of the age.

The densely built city centre of Pest before 1900. The iron tower and the bridge would have stood here (Photo: Fortepan, Budapest Archives. No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.07.109)

Of course, it was not only János Ruppenthal who came up with the idea of building some kind of transport on Gellért Hill. The funicular was an obvious idea (not only on this strange bridge but also from the foot of the hill) since the Buda Castle Hill Funicular had been operating in Budapest for 25 years at that time.

The funicular to Gellért Hill came up from time to time as a possible solution. The construction of the Erzsébet Bridge also involved the obligation of the tram companies to build the line to Gellért Hill. In addition, they envisioned not only a funicular to the hill but also a cablecar connection, one that would have started from Pest, over the Danube to the top of the hill.

Cover photo: Gellért Hill from Pest before 1900 (Photo: Fortepan, Budapest Archives. No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.093)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration