A special discovery was made by construction workers on today's Hajógyári Island, in the area of the shipyard on 19 May 1851: they discovered Roman ruins. The first excavation of the ruins itself was presented in 1854, at an academic meeting, by academician János Érdy, the guardian of the Academy's coins collection. The speech was described in the Akadémiai Értesítő, issue 1854/5:

"The island of the shipyard in Óbuda was connected in 1851 by an embankment to a large island extending beyond its upper peak; The ruins of the Roman buildings buried in the upper part of the shipyard served as good materials for the embankment. Several of us went out here on 19 May, on 28 May etc. 1851 for archaeological research. I visited these shipyard excavations several times in the company of István Nagy, dr. János Szabó, János Jerney, Iván Paúr, János Varsány and others, where two caldariums or a sweating bath were excavated in front of us”

The fact that there were Roman ruins on the island was certain for decades before the find. During the construction of the shipyard in 1835, the Vida dredger collided with Roman walls. However, for the first time, experts went out into the area for archaeological excavations.

Flóris Rómer priest, archaeologist, freedom fighter, who conducted the first research on the Hajgyári Island (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

A bench placed on columns, stone walls, and epigraphic bricks bearing the inscription LEG II HAD were found, which tied the artefacts to the age of Hadrian. Of course, they didn't know what the earth was really hiding.

Professional excavations began in 1854 under the leadership of Flóris Rómer. It was delayed until then because Rómer had served his prison sentence for his role in the war of independence (he enlisted in the army, despite being a monk, he started as a private, but reached the rank of a captain by the end of the war).

The excavation continued until 1857 under the leadership of Flóris Rómer and Gusztáv Zsigmondy. The richly decorated walls, identified as part of a Roman bath, stood several meters high.

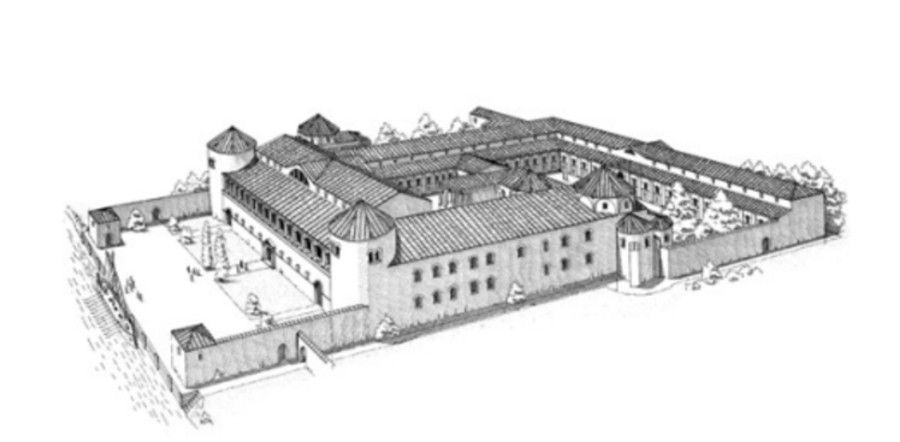

Ruins of the governor's palace. The artefacts from the site and some of the murals and mosaics are presented in the permanent exhibition of the Aquincum Museum (Source: Aquincum Museum)

The shipyard proudly displayed the excavated Roman relics. Even the imperial family visited it. However, due to the needs of the factory, the walls were demolished, and other alterations were made, such as pipes were passed through the excavated rooms or they were used as warehouses, and then the remains were reburied at the end of the century.

Another excavation took place between 1941 and 1956 in several instalments. It was then that it became clear that the buildings here did not belong to a bath but to the ruins of the governor's palace. The palace operated until the end of the 3rd century and was rebuilt and expanded several times. The palace itself was found to be a 120-by-150-meter-long building that included nearly a hundred rooms. Archaeologists were able to determine the purpose of many.

Excavation work in 1951, almost 100 days after the discovery of the ruins (Source: Szabad Nép, 10 May 1951)

In the 1990s, between 1996 and 1998, further excavations were carried out in the area, and it was then that the true size of the ruin complex was revealed. Hadrian's palace covers about 7 hectares, although the previously excavated palace is the main building of the whole complex, only a part of it.

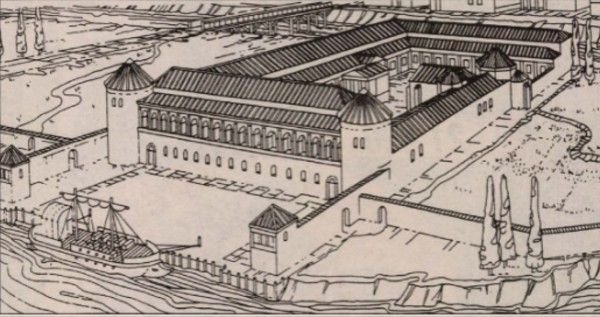

View of the governor's palace based on a drawing by architect Gyula Hajnóczi. The main facade of the building complex faced the former Danube branch (now the Hajógyári Bay). According to archaeological research, the governor also had his own port.

Katalin H. Kérő, in her article entitled Fővárosi régészet: mit rejt a Hajógyári sziget (Metropolitan Archeology: What the Shipyard Island hides), which was published in the 1998 issue of Magyar Múzeumok, described the former palace as follows:

"The main building of the governor's palace. The villa included the governor's residence, reception and office rooms, and utility and service rooms. The two-story main façade of the palace with porticus faced east. There may have been a harbour in the foyer. The stairs led to the upstairs gallery from the corner towers. The floors of the reception halls on the ground floor were covered with black and white mosaics with a geometric pattern, and the walls and ceilings were decorated with murals. These were repainted several times according to the changing fashion of the age. From the reception halls, access was provided to the corridor surrounding the inner courtyard, from where the north and south wings were accessible. The former housed the living and bathrooms, the design of which was also luxurious. The toilet was decorated with a geometric mosaic floor. A sea scene was captured on the colourful floor of one of the swimming pools, and another wall was adorned with a figurative representation painted on a blue background. (…) The inner courtyard was decorated with a dolphin fountain. For the convenience of the residents, underfloor and wall heating, as well as plumbing and sewerage system was built."

The significance of the ruins here is that experts know of the remains of only five governor's palaces in the former Roman Empire, and this palace is one of the best-documented sites.

Emperor Hadrian (76–138) built the palace of Aquincum in his time as governor

Why can the area not be visited? Why don't tourists come here? The palace is not visible today. It is underground, as it was buried after the excavations. There is now a golf course above it. The fact that ruins are reburied after excavation is common in archaeological sites, as professional reburial protects vulnerable parts from further destruction.

What to do with the palace, whether to make the ruins accessible or to rebuild the governor's palace in some form, has been the subject of various plans and ideas for years.

Cover photo: The former governor's palace based on a drawing by architect Gyula Hajnóczi

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration