"Flourish!" - with this exclamation, on 3 March 1846, the wife of István Széchenyi, Seilern Crescence, planted the first sycamore tree in the first promenade of Pest, in today's Szabadság Square, on the southern side of the barracks that once stood there called Újépület. The construction of the Pest promenade was initiated by Széchenyi, in 1845 he also organized a company for this purpose from the house owners living in the area and their residents, called Séta-tér-Egyesület. After both the Pest and Viennese authorities authorized the establishment of the park, the first trees were planted in March 1846 and the Sétatér was born.

The plaque of the well on Szabadság Square shows the scene when Seilern Crescence is planting the first tree of the Pest promenade. The well is the work of sculptor Ede Telcs and architect András Mészáros (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

István Széchenyi was not there at the ceremony, as he was negotiating in Vienna. However, there are no records of the presence of Countess Blanka Teleki, who lived in one of the houses in the square (later in 2 Sétatér and after that in 3 Szabadság Square), where, according to contemporary reports, “every lady, high-ranking as well as bourgeois-class, who was present, watered the inaugurated place and sapling. ”

It is certain that Teleki Blanka not only monitored the further work of the park as a resident there, but also as an interested party in the events of the Pest reform era. Perhaps the sight of the deciduous trees also inspired her to carry out her plan: the creation of a novel school that educated national ideas for the daughters of aristocratic families.

As early as December 1845, while hiding behind the pseudonym “a patriot peer”, Blanka Teleki raised the need for a school for girls in an editorial published in the Pesti Hírlap, in which "the sacred love of homeland should be instilled in the heart of the adolescent girl together with the mother tongue. . ” The Countess was disappointed to see that the daughters of the main families were taught by foreign educators who did not teach the Hungarian language and the history of the nation. In the already mentioned article published in Pesti Hírlap, she said:

"Hungary's daughter, who speaks three-four other languages, knows the history and current state of any nation well - but she doesn't understand her national language, she has no pictures of her country's past and its current struggle is often an object of mockery for her."

Half a year after the publication of the article, in the summer of 1846, she had already published the “curriculum” of her own school for girls and the conditions of admission. She was expecting girls aged 8-12 at her institute, and the cost of boarding and education was 350 pengő a year. Piano lessons cost another 80 pengő, but this was not mandatory.

The school was opened in the already mentioned building at the former 2 Sétatér (now 3 Szabadság Square) and used teaching methods different from those of the time. The biggest novelty was that the teaching was conducted in Hungarian, and the subjects were taught by specialist teachers in today's terms: literature and history by Pál Vasvári, and natural sciences by the Piarist zoologist János Hanák. Klára Leövey worked as an educator at the institute. Later, music teacher and composer Károly Them and János Argai, a teacher of quantitative studies at the Lutheran grammar school in Pest, also taught here.

Today, a plaque on 3 Szabadság Square indicates that Countess Blanka Teleki's institute for women's education operated here (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

Despite all this, the students did not crowd into the institute. In the year of the opening, only one girl was registered: Baroness Rózsa Puteáni, daughter of the later Member of Parliament in '48, József Puteáni, goddaughter of Ferenc Deák. Beside her, Erzsi Erdélyi studied at the institute, she was a so-called free student and was patronized by Teréz Brunszvik, the aunt of Blanka Teleki, a kindergarten founder.

Ferenc Deák is said to have praised the new institute throughout the city, perhaps this is also why it has become increasingly popular. Although the figures for the number of students are not clear - there are 11 students in 1847 and 17 in other sources, and in 1848 there are already over-registrations - it is certain that the girls were receptive to science and national ideas. A good example of this is the dissertation written at the age of 11 by the aforementioned student, Rózsa Puteáni, which was published in Teleki Blanka és köre. Karacs Teréz, Teleki Blanka, Lővei Klára [Blanka Teleki and her circle.] edited by Györgyi Sáfrán in 1963:

“In ten years, I will set up an institute in Pest, and I will take girls and raise them to be Hungarian and patriotic women. The study rooms will be [furnished] with very little furniture, there will be plenty of chairs and tables, the writing rooms will be separate again. Otherwise, nothing will be gaudy, but everything will be simple. Many times we will take big walks, big ones with bigger girls and smaller ones with smaller ones. And my main goal will be to make the little girls real Hungarians, my company will always be with smart people. My outfit will be simple and I will never be dressed up. Before I start the institute, I go to travel, travel in my home country, then abroad, and if possible, go to America as well. Then I will teach my little brother until the age of 10, and when I am 21, I will set up an institute in Pest, in which the Countess [Teleki Blanka] shows me the most beautiful and noble example, and I want to follow her, because there is no more beautiful and greater life here, like hers. In order for my wishes to come true, I will spend the first few years learning a lot and useful things, being able to let others know, and then I want to travel. ”

The revolution of 1848 further inspired the students, although they were forced to say goodbye to their enthusiastic teacher: Pál Vasvári took up the position of secretary at the Ministry of the Interior of the newly formed government, and then at the Minister of Finance, Lajos Kossuth. Blanka Teleki's women's education institute ordered the well-known portrait of Vasvári from Miklós Barabás as a farewell gift. Below the picture is the inscription: "In gratitude to their teacher, the laurels of the Teleki Blanka Women's Education Institute, 15 March 1848."

The well-known portrait of Pál Vasvári was commissioned by the students of the Blanka Teleki Institute of Women's Education from the painter Miklós Barabás, as a sign of their gratitude. Vasvári taught literature and history at the institute from 1846 to 15 March 1848 (Source: Hungarian Digital Archive)

Seeing the events of the War of Independence, in December 1848 Teleki Blanka decided to close the institute. She traveled to Debrecen, then at the end of 1849 she retreated to one of the family estates, Pálfalva, and helped the former freedom fighters escape. She was arrested by the imperial police in May 1851 and transported to Pest in October.

A peculiar twist of fate is that she spent her two years of probation in the Újépület, then known as a prison and a scaffold, next to her former beloved school. According to the accusation, the revolution started from her educational institution, her books and translations preached rebellious ideas. A court-martial sentence in June 1853 sentenced her to 10 years in prison, most of which she spent in Kufstein Castle, and was then released on amnesty six years later. Although she returned to Pest, she saw from her home in the Sétatér - then called the Széchenyi promenade - her former prison. Maybe that’s why - and because of constant police surveillance - she decided to go into voluntary exile and travel abroad.

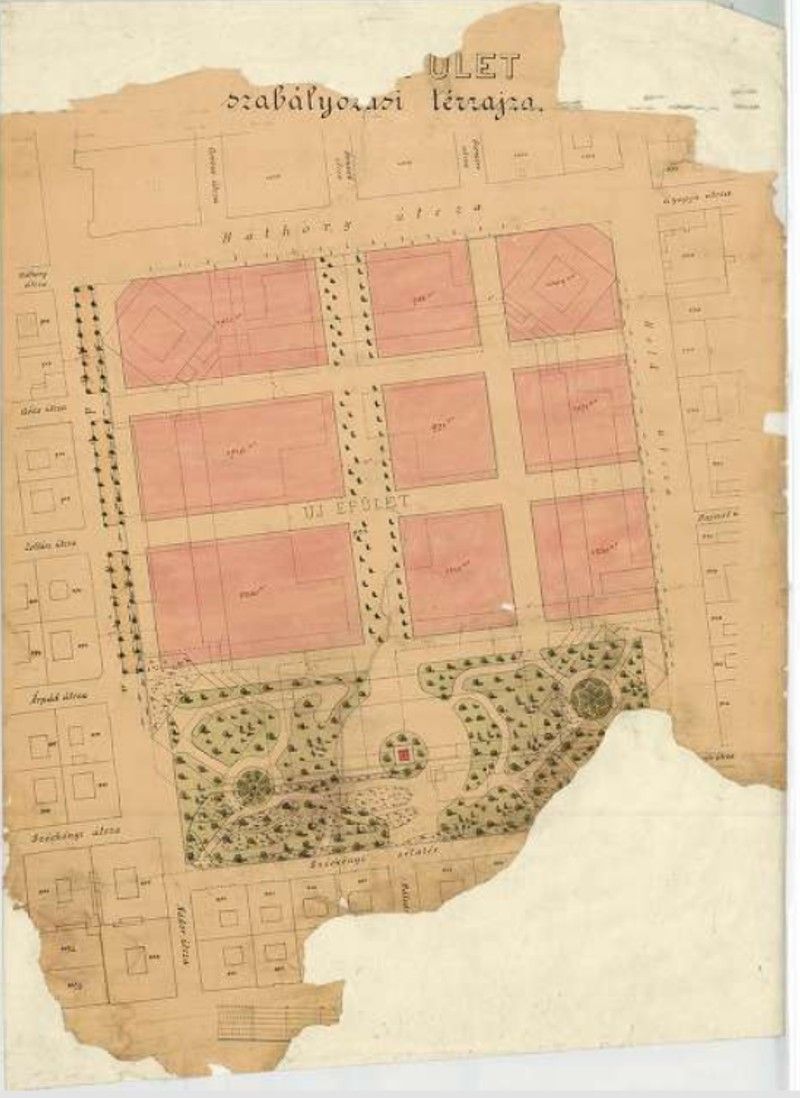

Spatial plan made around 1860 about the Újépület, the Sétatér and the buildings there (Source: Budapest Capital Archives. Reference No.: BFL XV.16.b.224 / 66)

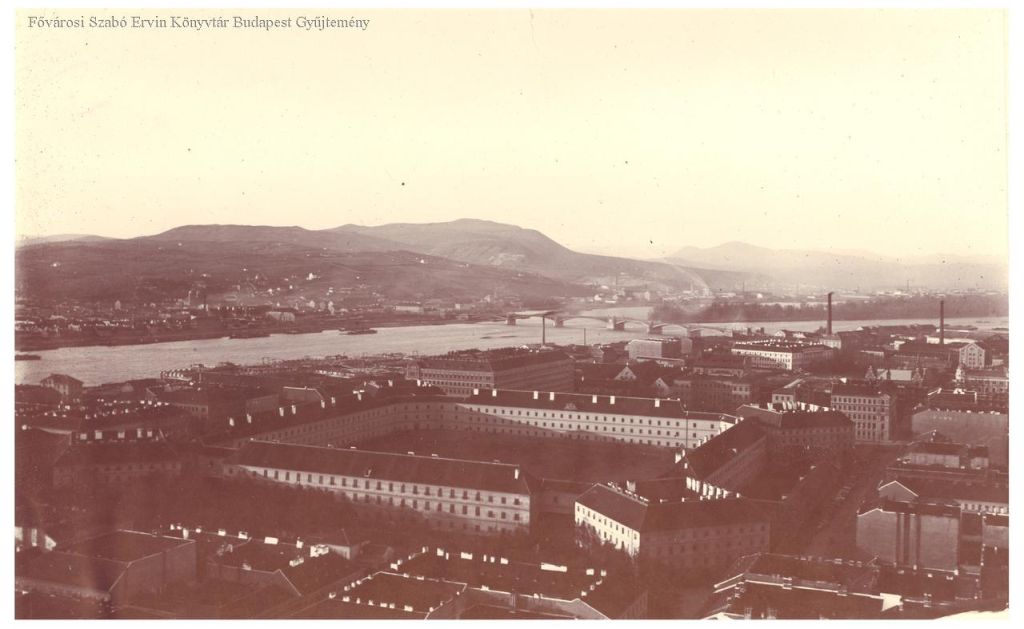

The infamous Újépület from the tower of the Basilica, photographed by Ödön Téry, around 1896. The huge building was originally built as a barracks, then after the fall of the revolution and the war of independence in 1848–49, Hungarian patriots, Blanka Teleki, among others, were locked up here in mass, thus becoming a symbol of retaliation. Count Lajos Batthyány, the Prime Minister of the first independent Hungarian government, was executed in the courtyard of the building on 6 October 1849 (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

The building, which housed the former popular school for girls and the apartment of Teleki Blanka, was bought by János Ebner Nepomuk in 1867 and extended by a new floor according to the plans of József Limburszky. Three years later, in 1870, new alterations were made to the building by order of Baroness Petronella Rudits, this time the designer was again József Limburszky.

In 1904, the Hungarian National Central Savings Bank bought the building for 250,000 HUF, which was then converted according to the plans of Dezső Hültl. On the ground floor there was a bank branch, to which two huge vaults were also built. Upstairs, an apartment was created. The bank branch operated until 1948, after the nationalization the building was transferred to the Ministry of the Interior, and was used by the economic police. After the change of regime, since 1994 the headquarters of the Catholic Camp Bishopric has been operating in the building.

Today, the headquarters of the Catholic Camp Bishopric operates in the building 3 Szabadság Square (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

Cover photo: 3 Szabadság Square, formerly 2 Sétatér. Countess Blanka Teleki's school for girls operated here (Photo: Balázs Both / pestbuda.hu)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration