The idea of connecting the Városliget with the Inner city and Lipótváros came up during the Reform era. This wish was expressed in the Pesti Hírlap edited by Lajos Kossuth in 1841 in an article titled What does the city of Pest need to take on the role of a capital?:

“[…] What a nice comfort for the people of Budapest between this shady series of trees, from the chain bridge to the city forest, to walk around like in a park, to get around the narrow, ugly Király street and its boring endless row of houses! - It really is inconceivable how this institution would dress our city in such an ornate shape."

Count Gyula Andrássy on a photo by József Borsos, 1865–1867 (source: FSZEK, Budapest Collection)

Until the construction of the Sugárút [Avenue], ie today's Andrássy Avenue, it was only possible to get to Városliget via the very neglected, dirty and narrow Király Street. However, this situation did not suit the recovering Pest in any way after the compromise. The same view was expressed by Count Gyula Andrássy (Prime Minister from 1867), who during his emigration to Paris after the Hungarian War of Independence was able to see Baron Hausmann's great urban planning activities in person, which inspired him to speak up for an avenue in Pest. He first proposed the construction of a representative route at the opening meeting of the Pest-Buda Joint Beautification Committee in 1868. According to an urban legend, it was not just the Champs-Elysées that gave the idea to Andrássy.

"It is said about Andrássy Avenue that it was torn out of the old inner town of Terézváros and the outer fields and gardens of Terézváros, because Count Gyula Andrássy, the prime minister, was ashamed that the queen had to drive to the Városliget on the winding, narrow Király Street."

- writes the Pesti Napló on 26 August 1905.

An idea about what Andrássy Avenue should look like around 1870 (source: FSZEK, Budapest collection)

Whatever the reality was, thanks to the strong support of Andrássy and Lajos Tisza (Vice-President of the Budapest Public Works Council), the House of Representatives finally voted in 1870 to build the Avenue. Some MPs opposed the idea because it was seen as a luxury investment the country could not afford.

"But they would not be in favour of the planned main transport avenue, even if it were of real national interest, because it would be necessary to maintain a certain order in the works to be built with the country's money, and it would be levity to vote 8,000,000 ft for an esplanade."

- reports to the Politikai Ujdonságok in December 1870, just before the idea was voted on.

Sándor Országh, head of one of the departments of the Budapest Public Works Council, went further in his work entitled Budapest középítkezései [Public Constructions of Budapest], published in 1885:

"There were many who attributed it directly to the aristocratic whims of Count Gyula Andrássy and Lajos Tisza, who saw nothing but a new corso on which the lords could carry out their riding practices or drive their bright coaches into the Városliget."

A contemporary caricature of Count Gyula Andrássy and Lajos Tisza as they plan the Avenue (source: Üstökös, 1 July 1871)

The opening of a new road was a major urban planning task that had to be overseen by the Budapest Public Works Council, established in 1870. The first issue to be decided was the designation of the road section. For this, the technical department prepared four route plans, of which they chose Könyök Street.

“Könyök street was very nice. It had the most romantic stone paving in the city. It was home to the easternmost beauties of the city. The lewdest shoes and pants were sold in it. The most kosher goose legs were sold there. ”

- writes the satirical magazine entitled Bolond Miska of the designated street in November 1870.

Stinky, dirty side streets and small dilapidated houses once stood on the site of ornate palaces. The contemporary press described it as a very dangerous part of town, especially around today's Oktogon, where murders were very common. In 1871, the Budapest Public Works Council acquired 207 buildings due to the construction of the new road. Most of the ground-floor buildings were demolished, old cellars and digestion pits were filled, the ground levelled, canals were constructed and the problem of public lighting was also solved. However, these tasks had been performed by the Sugárúti Építő Vállalat [Avenue Construction Company], which signed a contract with the Budapest Public Works Council on 9 March 1872.

Depiction of Andrássy Avenue in 1875 (source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 30 May 1875)

The company began the constructions. Miklós Ybl and István Linzbauer were asked to prepare the preliminary plans, in which several architects became involved. The first building permit was issued in July 1872 for the plot of land between Nagymező Street and Gyár Street, the so-called Hétház [Seven houses] (today 32–44 Andrássy Avenue). The building complex consists of three four-storey and four three-storey houses, each with a separate entrance. The company certainly planned a completely unified route full of houses like this. However, due to the stock market crash of 1873, construction slowed down and the Avenue Construction Company went completely bankrupt. Therefore, the burden of road construction was again placed on the Budapest Public Works Council, whose main task from then on was to sell the parcelled land. The price of the plots offered for sale was not uniform: while on the corner of Váci Road it was 500-600 forints per square meter, in the vicinity of Liget it did not even reach 30 forints.

Andrássy Road facing the Városliget in 1878. On the left is the so-called Seven Houses (source: Fortepan / No.: 82162).

The plots proved to be small in several cases, so it was common at the start of construction for some to be distributed among several plots or to merge two adjacent areas. The reason for this is to be found in inexperience, as there has not been such a large-scale allocation of land in Pest so far. The avenue had to be renumbered twice until the official handover, 1885, due to area corrections.

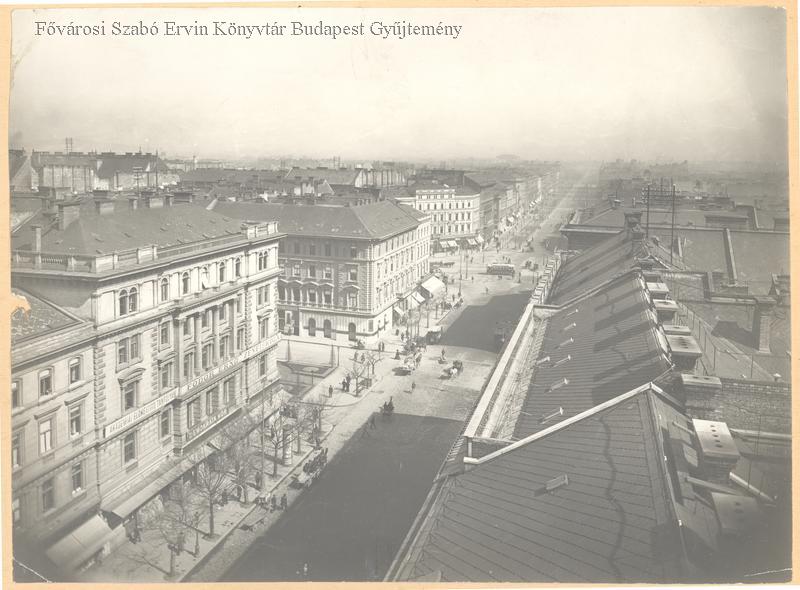

Andrássy Avenue towards Heroes' Square (source: FSZEK, Budapest collection)

The plots were bought by insurance companies and banks, aristocrats, the bourgeoisie and the upper middle class, who with their financial background managed to move the huge enterprise out of the deadlock. For private builders, the Public Works Council could not prescribe a uniform style appearance, it could only impose a few building rules (e.g., cornice height, number of floors, degree of built-in). Nevertheless, it shows a unified picture, as the buildings of the route follow the forms of historicism, primarily the Neo-Renaissance. The palaces on Andrássy Avenue resemble the complexes of buildings erected in Vienna and the cities of Germany, as ironically noted in the 4 June 1882 issue of the Vasárnapi Ujság:

“... the avenue mimics the new palaces in Vienna. Some are total copies. No wonder it was the work of foreign architects who brought the character of Vienna and Berlin among the stones. ”

Andrássy Avenue before the handover in 1885 (source: Ország-Világ 18 April, 1885)

The Avenue was opened gradually. On 20 August 1876, pedestrians were able to take possession of the Avenue to Oktogon, then known as Nyolcszögtér. By October of the following year, they had been able to use it all the way. The last plots of land were purchased in 1884, but by then most of the palaces had been built. The full handover took place on 1 May 1885, the day before the opening of the national exhibition.

The Avenue is divided into three parts by the two regular squares, the Oktogon and the Körönd. In the first section, up to Oktogon, there are three- and four-storey buildings, with shops, restaurants and cafés on the ground floors. In the second section, to Körönd is lined with two- and three-story palaces. The last section is divided into two parts by Bajza Street: the buildings were closed to Körönd, while the villas with free-standing gardens were planned towards Városliget.

The Oktogon circa 1897 (source: Fortepan / No.: 24118)

The Kodály Körönd in the 1890s (source: Fortepan / No.: 82458)

At that time, it was not really effective to close the road on the side of the Városliget. On the site of Heroes' Square stood a well, over which in 1884 a building called Gloriette was built according to Ybl's plans. A staircase led up from the two sides to the 2.5-meter-high, hexagonal, fenced terrace, and in the middle was a 24-meter-high flagpole. The building was moved to Széchenyi Hill due to the construction of the Millennium Monument.

Ybl's Gloriette on the site of Heroes' Square in the early 1890s (source: Fortepan / No.: 82464)

The estuary of Andrássy Avenue and Dózsa György Road (then Aréna Road), with the Edelsheim – Gyulai villa in the background. To the right is the location of the later Heroes' Square (source: Fortepan / No.: 82284)

The name of the route has changed several times over time. After its opening in 1877, it was simply referred to as Sugárút [Avenue], and in 1885 it was renamed Andrássy Avenue in honor of Count Andrássy. From 1949 it's official name was Sztálin Road, in 1956 it was Magyar Ifjúság útja [Road of the Hungarian Youth] for a very short time, and from 1957 it was Népköztársaság útja [Road of the People's Republic]. It regained its original name, Andrássy Avenue, after the change of regime.

Oktogon and Körönd also had similar name changes. The Oktogon was called Mussolini Square for a short time, then November 7 Square, while the Körönd was named after Hitler and then its famous resident, Zoltán Kodály.

The preservation of the image of Andrássy Road was set as a goal as early as 1886, which was confirmed several times afterwards. The most beautiful “promenade” of the capital is not only protected as a monument, but has been a World Heritage Site since 2002.

Cover photo: Andrássy Avenue at Oktogon in the direction of Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Road (source: Fortepan / No.: 82280)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration