Béla Lajta was born on 23 January 1873 in Óbuda under the name Béla Leitersdorfer. He completed his architectural studies in Budapest, and after graduating in 1896, he continued his education in Rome, Berlin and London with a scholarship. He followed Hungarian architectural public life from afar and was greatly influenced by the Hungarian design style of Ödön Lechner, so after his arrival home in 1899 he became a follower of the master. Therefore, he also sought the foundations for the creation of national architecture in folk art.

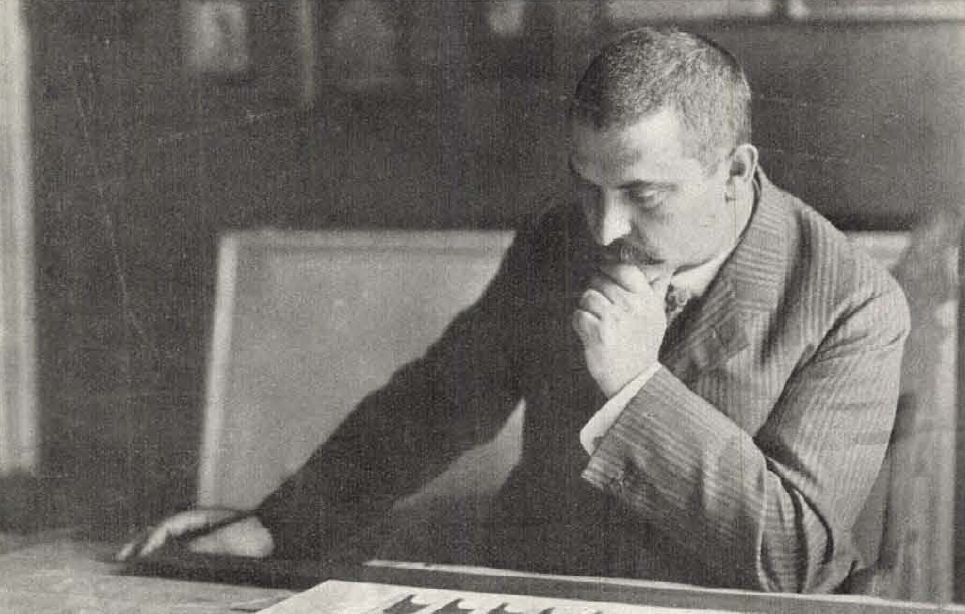

Béla Lajta at his desk (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 15 October 1911)

This trend attracted crowds of young architects and enriched Budapest with many wonderful works; from Lajta, perhaps the Schmidl Mausoleum in the Jewish cemetery on Kozma Street is worth highlighting. However, the undulating progress of human culture, which had been experienced before, showed itself again around 1910, and after the growing Art Nouveau, which affected the emotions, the more rational and cooler classicism became stronger. Lajta's genius is also shown by the fact that he recognised this change very quickly.

The beautiful mausoleum of the Schmidl Family (Photo: Máté Millisits/pestbuda.hu)

In short, classicism means going back to the forms of ancient Greco-Roman architecture, which - being the roots of European culture - have been considered a solid foundation and an example to be followed since the Renaissance. This was first-class art, hence the root of the word classicism. In these ancient times, they built from simpler elements, and elementary geometric masses were characteristic, especially of the Greeks. The stable forms and the antiquity of the style simultaneously created a sense of permanence and reliability, which was increasingly sought by the intellect as a counter-effect of Art Nouveau.

This was not the first appearance of classicism in European architecture, it was also the main current of art a century earlier. In Hungary, it was especially fashionable during the Reform era, which can be considered one of the most successful periods in the history of the country, since, after a long period of stagnation, it finally started on the path of embourgeoisement. This did not only mean economic changes, culture also reached a new level as a result of the strengthening national consciousness.

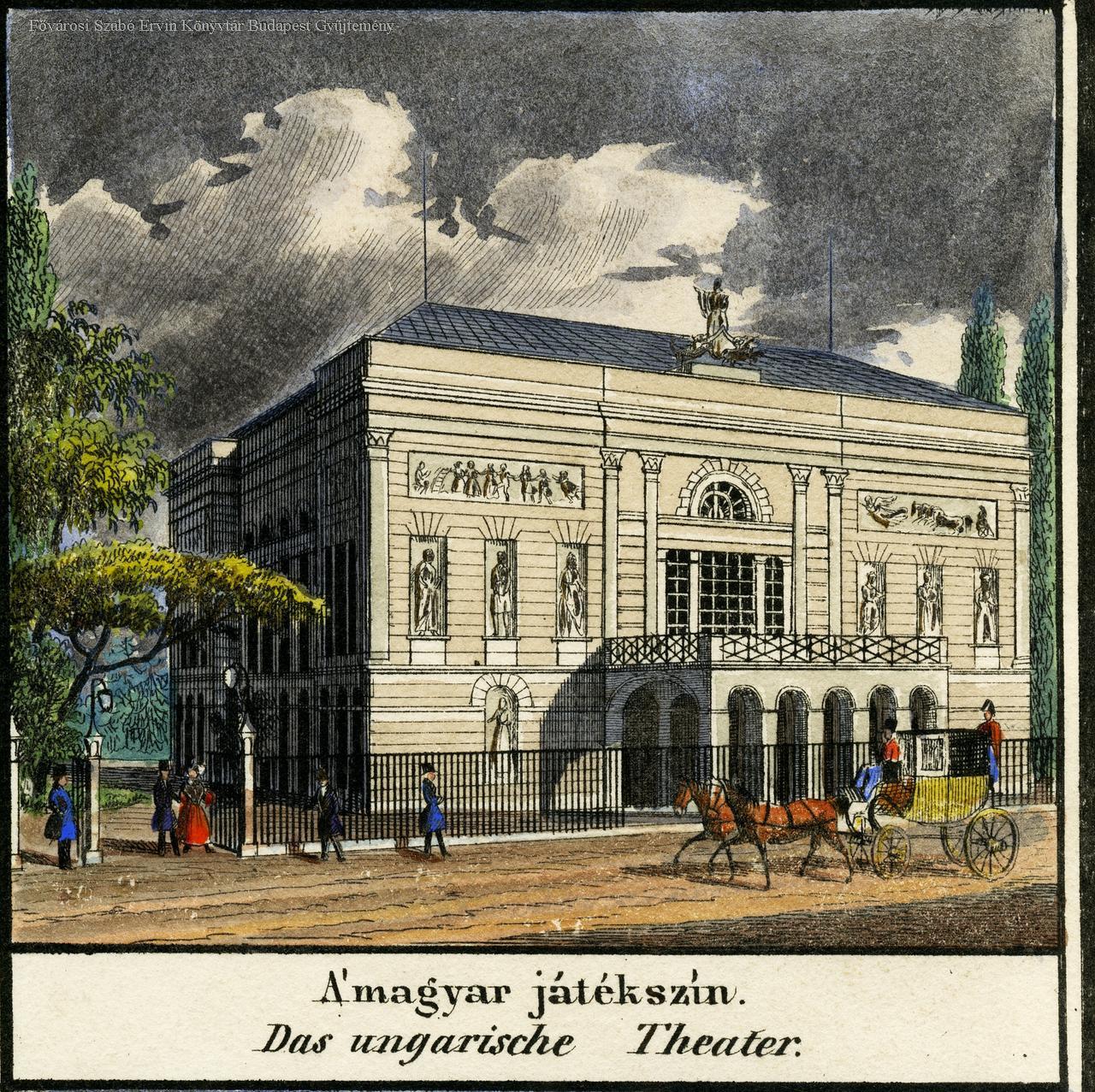

Carl Vasquez's 1837 engraving of the Hungarian Theatre in Pest (Source: FSZEK Budapest Collection)

This was also evident in the field of acting, more and more plays were performed in Hungarian, although only the German company had its permanent theatre in today's Vörösmarty Square. In accordance with national needs, a movement was also started to establish a Hungarian stone theatre. However, since it had a much more modest financial background, they only managed to acquire a plot of land for the building outside the city walls, near the former Hatvani Gate. At the junction of today's Múzeum Boulevard and Rákóczi Road, the Hungarian Theatre of Pest was finally built in 1837 according to Mátyás Zitterbarth Jr.'s plans. The National Assembly took it under its protection in 1840 and declared it a National Theatre.

The building frenzy after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise also affected the theatre: in 1875, according to the Neo-Renaissance plans of Antal Szkalnitzky, its facade was remodelled and residential houses were built on both sides. The corner of the building facing Múzeum Boulevard was rounded, and the top was emphasised with a distinctive dome. The theatre also gained extra income from rental fees, but unfortunately, it was not used for modernisation, so it became obsolete by the beginning of the 20th century and was even declared life-threatening in 1908 and then closed. Its demolition became inevitable, but its walls were still standing when a professional debate began about the new National Theatre and its location.

The apartment building built next to the National Theatre was crowned by a dome (Source: Fortepan/Budapest Archives, Reference No.: HU.BFL.XV.19.d.1.05.148)

At the beginning of 1911, the Association of Hungarian Architects announced a conceptual tender, in which the task was to build on the previous plot. 26 designs were submitted to the competition, which was held with quite a lot of interest, of which Béla Lajta's was chosen as the best. The second prize went to Ferenc Stobbe, the third to Győző Lichtmann. The Association did not expect detailed plans, they were only looking for ideas on the possibilities of building. Lajta's triumph also shows that he was not only good at drawing facades, but also floor plans and spatial organisation.

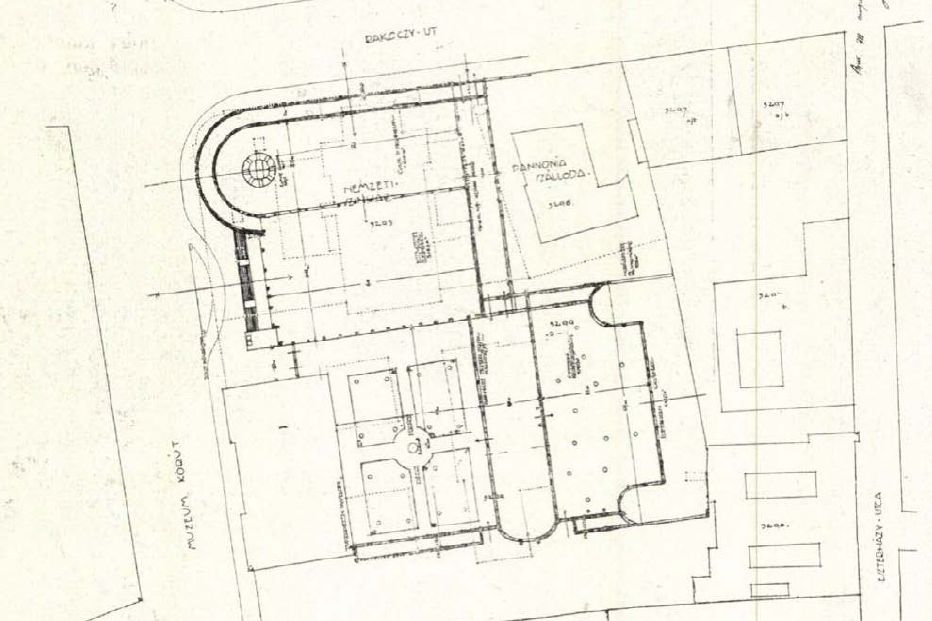

Site plan of Lajta's winning track plan (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 15 October 1911)

Functional thinking led to the fact that, together with the theatre, this important traffic junction of Budapest must also be arranged, because due to the increased traffic, it has already become dangerous. For this reason, he would have widened Rákóczi Road and left enough space at the far end of the plot - facing today's ELTE - so that if a tram line were built from the inner city to Józsefváros, then the tracks would be routed there. In addition to traffic, this open space would also be suitable for a smaller park, in which the theatre's café could operate in the summer.

He would have built the lot in a very airy way towards Rákóczi Road, as the theatre would not have extended to the line of the road, instead it would have formed a space twenty-five metres wide and seventy-five metres long, bordered by arcades. This would have opened up the possibility of locating shops, the rent of which would have generated income for the institution. According to the layout plan, the main facade facing Múzeum Boulevard would also have moved back about twenty metres from the roadway, so there would have been plenty of room for a long snaking line in front of the entrance.

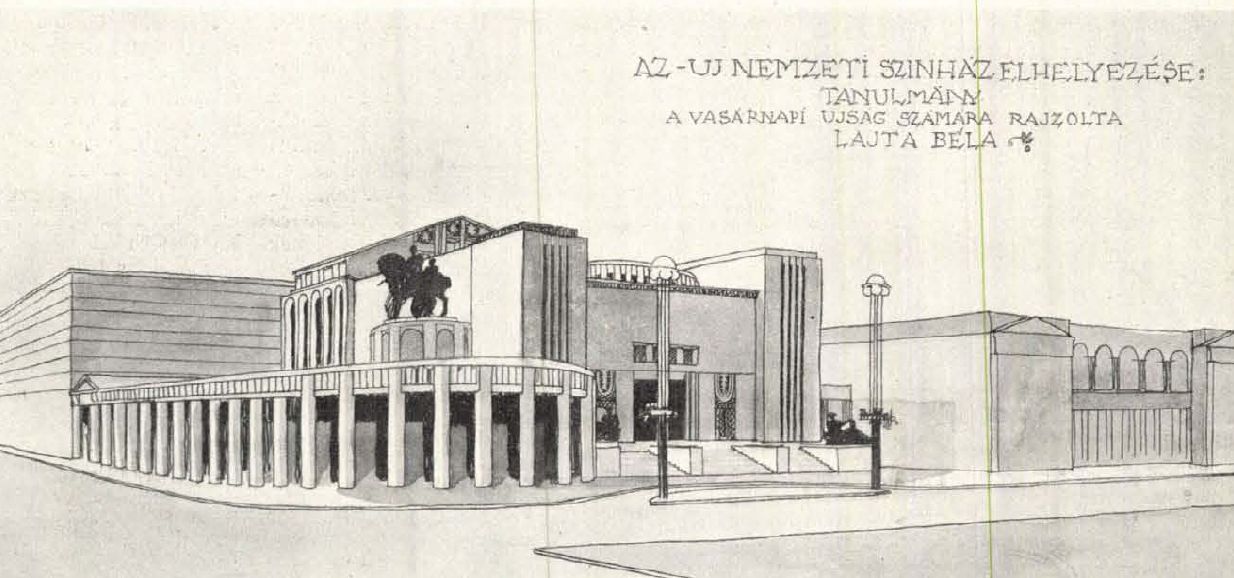

Perspective view of Lajta's plan (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 15 October 1911)

The style of the building shown on the plan is characterised by classicism, as it is built from large, elementary geometric shapes: the main facade with a straight closure is joined on both sides by taller columns, the tops of which are also flat. Only the rear tract was given a gable roof, presumably, this would have included the fly system above the stage. The windows, on the other hand, are narrow and strongly stretched upward. Lajta would have led the arcades facing Rákóczi Road in a semi-circle at the corner of the lot, thus referring to the mass formation of the former National Theatre. Although he imagined an equestrian statue placed on a high plinth which would have properly emphasised this urbanistically important intersection, not a corner dome.

The Association of Hungarian Architects forwarded Lajta's plans to the Ministry of Religion and Public Education - which managed the construction of the new theatre - with the comment that there are ideas worth considering, which should be taken into account when the public design competition is announced. This happened twice in the following years, for which Béla Lajta submitted several plan versions. This also indicates his commitment towards the matter: it would probably have been one of his greatest dreams to design the new National Theatre.

However, he did not achieve real success in these competitions, he only received the fourth prize in the first competition held at the very beginning of 1913. The criticism published in the contemporary press found the reason for this in the following:

"That impressive simplicity, which in most cases is an excellent aid to the monumentality required in architecture - it is enough to mention Lajta's Vas Street masterpiece, the facade of the commercial school - was intensified to the point of bleakness in both of the works submitted for tender by the National Theatre. We want more style on it […].”

The plan is truly ahead of its time and can almost be compared to the simplicity of the Bauhaus, although classicising forms appear on it: the main entrance opens behind an eight-column, tympanum gate and Lajta also created a stepped attic gable on top of the main facade. And the construction of the fly tower was reminiscent of ancient Greek temples. No matter how puritanical the design, statues were placed on it: the main entrance is guarded by equestrian statues on high pedestals on both sides.

Béla Lajta's fourth prize-winning design (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 26 January 1913)

The top four winners of the previous round were invited to the second, smaller competition held in the spring of 1913. To this, Lajta submitted three plans, but they were not successful either, the couple Emil Tőry and Móric Pogány were declared the final winners. The old building was largely demolished in the fall of 1913, but due to the outbreak of World War I, the construction of the new building was off the agenda. New attempts were made to organise the vacant lot only during the period of consolidation after the revolutions: a temporary cinema called Nemzeti Mozgó (National Motion) was supposed to be established, but that did not materialise either. Béla Lajta did not see the theatre's further ordeal, he passed away on 12 October 1920, at the age of only forty-seven.

Pestbuda's previous article written on the centenary of his death can be read here.

Cover photo: Béla Lajta's plan for the National Theatre (Source: Vasárnapi Ujság, 26 January 1913)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration