If we drive out of the city centre on Üllői Road, Ady Endre Road, one of the main traffic routes in Kispest, branches off from this long - the longest boulevard in Central Europe. Almost from the beginning of the road, the church towers stand out: the Catholic Church of the Assumption is the tallest, but as you approach the Templom Square, the Reformed and Lutheran churches across the road become visible.

Postcard from Kispest from the first half of the 20th century (Source: hungaricana.hu)

Yet there was hardly anything in this area a 150 years ago, it was even called Szentlőrincpuszta. In 1869, the part of this steppe closer to Pest was parcelled out and a settlement was established on it, which was declared a village two years later as a result of its rapid development. Kispest received city status in 1922, which was mainly due to the intensive growth of the population. Many of the settlers here were of the Lutheran religion, and the local Lutheran Parish was formed in 1894 as a result of their collaboration. Their leader was initially Sámuel Masznyi, a state teacher, so the first services were held at the Fő Street State Elementary School.

Although they received land from the village of Kispest in 1901 for the construction of a church, a rectory and a cantor house, they could not think of the construction for many years. They strengthened organisationally, leaving the former branch church in 1907 to become an independent pastoral station, and in 1922, after raising Kispest to the rank of a city, it became a main church.

The Reformed Church and Palace of Culture in Kispest (Source: National Széchényi Library)

The revolutionary atmosphere after the First World War also affected the churches: in 1918, worship was banned in state-run schools. The homeless Lutheran congregation was helped and welcomed by the Reformed in their own church, which was built in the last years of the 19th century. This was only imagined as a temporary solution by the faithful, so they began fundraising and by the summer of 1924 were able to get there to lay the foundation stone of their own church. The ceremony took place on 9 June.

The first plans for the building were made by the young architect and decorative artist György Lehoczky, but they were not approved by Pál Lipták, engineer, Secretary of State of the Ministry of Commerce. He suggested that the parish entrust the more experienced Gyula Sándy with the preparation of the new plans, who, as a faithful Lutheran, also knows exactly the special regulations of the denomination.

Portrait of Gyula Sándy from the 1920s (Source: Private Property)

The essence of a Lutheran church is to express in the language of architecture the unity of the pastor and the faithful, and thus of the whole congregation. To this end, it should consist of a single space in which the use of columns, pillars and other distractions should be avoided if possible. They would not only divide the interior of the building, but would also obstruct the view of the ceremony taking place in the sanctuary. Continuing the tradition of medieval church architecture, the sanctuary is also located in the Lutheran churches at the end of the longitudinally arranged part, but unlike the Catholics, only one can be there and its decoration is more restrained. Martin Luther, the founder of the denomination, did not forbid the placement of sacred images in the church, only guarded against their superstitious worship. Their motto and form of greeting is the "A mighty fortress is our God", which fortunately coincided with Sándy's architectural ideas.

Gyula Sándy came from the Highlands: he was born in Eperjes (Prešov) in 1868 and although the family moved to Buda when he was three, they often returned, mostly visiting relatives who remained in Rimaszombat. His painter father embarked on large-scale trips to gather inspiration for his landscapes and often took his son with him. He especially liked the ruins of medieval castles, which also revived interest in Romanian and Gothic architecture in little Gyula.

Gyula Sándy Sr.: Somoskő Castle (Source: Hungarian National Gallery)

After graduating from the Royal Joseph Polytechnic University, the castle-like masses of buildings already appeared on his first plans: bastions, towers, high roofs. A well-known element of the castles is the crenellated closure of the walls, which was mainly related to the protective function. In the Highlands, on the other hand, especially in the eastern part of it, simple residential houses were also built with crenellations during the Renaissance, in the 16th and 17th centuries. Sándy himself has seen many memories of this characteristic style since he was a child, and around the turn of the century he included them in his own architectural toolbox.

The Rákóczi House in Prešov (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

After the Treaty of Trianon, the crenellated renaissance style was particularly well-suited to the revisionist atmosphere, as it was also a reminder of the lost Highlands. The Lutheran church in Kispest is a manifestation of this and at the same time the opening of a whole long series: Sándy built a total of twenty-nine Lutheran churches after the two and, to a lesser extent, after the Second World War. He also made plans for much more than that.

At the request of the congregation in Kispest, Sándy prepared the plans for the church in April 1925, which of course complied with the religious regulations. Moreover, knowing the needs of the Lutheran ceremony, he invented new practical tricks that made it even more usable. For example, he has calibrated its capacity to a quarter of the total population of the congregation, because experience has shown that this ensures that the church is filled with the faithful and has no empty effect. He also limited the length of the interior - doubling the width - so that it was possible to avoid the faithful sitting in the back very far from the sanctuary and not seeing what was happening.

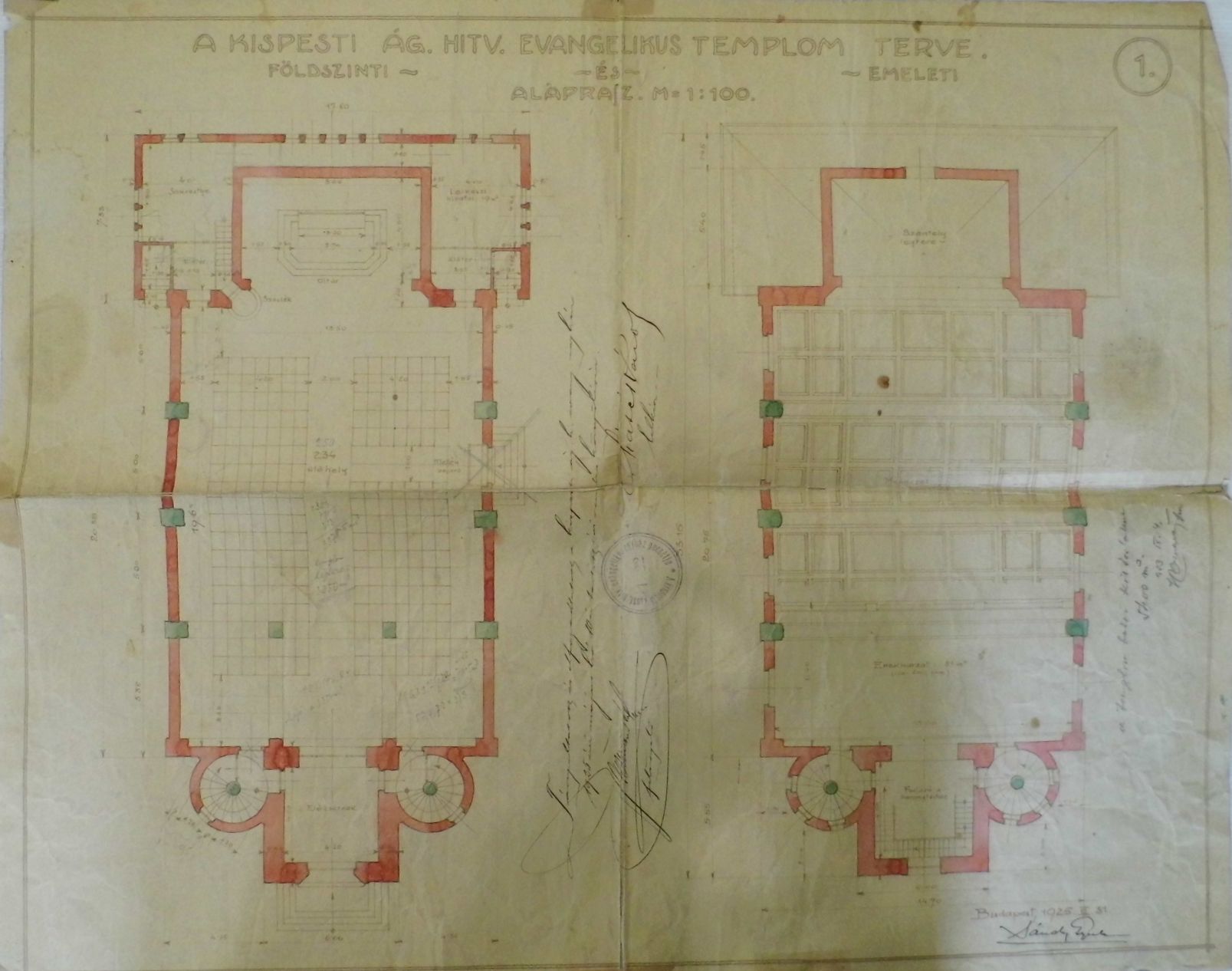

Floor plan of the Lutheran church in Kispest (Source: Archives of the Lutheran Parish of Kispest)

At the end of the church, he set up a shrine with a straight closure, surrounded by smaller ground-floor spaces: the sacristy on the left, the pastor's office on the right, and the corridor connecting them at the back. The main entrance of the church opens from Ady Endre - formerly known as Sárkány - Road at the bottom of the square tower. In addition to the tower, there are also two symmetrically designed staircases leading up to the gallery. The first plans also included an entrance in the middle of the right side facade, but in the end it was not realised. Reinforced concrete was used for the foundation and the reinforcing-dividing pillars of the side walls, but the walls were made of brick.

The main facade of the church (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The image of the church shows a mixture of Neo-Romanesque style and crenellated renaissance of the Highlands, the former represented by mass formation and semicircular door and window openings, the latter by the crenellations of the tower and stairwells, and the sgraffito tendrils and flowers covering the building. This technique, of Italian origin and name, means scraping back plasters applied in different colours, which also gives the shapes a kind of spatial effect. Although the entire facade is covered with yellow plaster, Sándy originally, like many of his later churches, envisioned a one-and-a-half-metre-high natural stone plinth that would have strengthened the castle-like neo-Romanesque character.

The sgraffito decoration also appears on the side facade (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

The tendril motifs similar to the exterior were also originally on the triumphal arch of the sanctuary (now adorned with larger, complex flowers, although the Christian symbols enclosed in the circles have survived), and the altarpiece and pulpit's speaker are adorned with a crenellation similar to the exterior. The interior is covered by a coffered ceiling with a trapezoidal cross-section, the shape of which was chosen by the designer for better acoustics. The church was painted only in 1936, but the work was still directed by Sándy. The interior was made by cabinet-maker György Fazekas. The solemn consecration was on 22 May 1927 by Bishop Sándor Raffay.

Elegant decoration of the interior (Photo: Péter Bodó/pestbuda.hu)

During World War II, there was serious damage, much of which was restored, but unfortunately not entirely according to the original plans: instead of sgraffito, the tendrils at the top of the tower can be seen as a traditional painting. The cross at the top of the turret, on the other hand, still retains traces of the battles: a projectile skewed it sideways, but this is not as spectacular as in the case of the Holy Crown. The church is in good condition and with its yellow colour it exudes a fresh atmosphere in the square, which is also adorned by the neat garden around it.

Cover photo: The Lutheran Church in Kispest (Photo: Krisztina Bélavári/Hungarian Museum of Architecture)

Hozzászólások

Log in or register to comment!

Login Registration